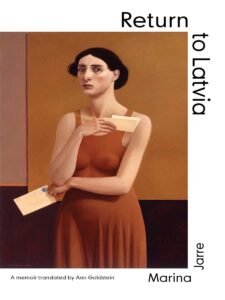

[New Vessel Press; 2023]

Tr. from the Italian by Ann Goldstein

Many writers have a memoir in them, but Italian writer Marina Jarre had two. The latest to arrive in English, Return to Latvia, continues a thread of inquiry begun in Distant Fathers that combines the personal—what happened to her father, a Latvian Jew, during World War II, and the historical—with a broader revisiting of the horrific crimes inflicted upon millions of innocent Jews and other targets, not just by the Nazis but, as Jarre astutely illustrates, by many others who handily assisted the Third Reich. This combination of wrenching personal history and profound past misdeeds that haunt us, makes for a compelling read that rarely flags. Jarre recounts a chapter in history we still do not fully understand, whose lessons we often fail to heed as anti-Semitism re-emerges again and again.

Jarre was born in Riga in the early part of the twentieth century to a mixed family of Italian Waldensians on one side and Russian Jews on the other. In her first memoir, Distant Fathers, she tells us that all her Jewish relations perished in the Holocaust. That book marked the author’s English language debut. She remains largely unknown in the US, yet in an indication of Jarre’s pedigree, both books were translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein, also known as Elena Ferrante’s translator. (Goldstein has also translated the work of seminal Holocaust chronicler, Primo Levi.)

In this new book, the author drills down on a gruesome episode: the slaughter at the end of 1941 of thousands of Latvian Jews, including her father, who was gunned down in a pit, after the author and her sister, Sisi, left Riga for her mother’s native Italy. Her parents had an acrimonious break, leading her mother to fear she would lose custody of Jarre and her sister. So, without informing her estranged husband, she spirited the children away clandestinely.

Her father’s plight—and indeed Jarre’s as a memoirist—is aptly captured by a letter she and her family received from him, which haunts the author (and the reader). She is unflinching as she reveals her indifference to her father’s message, which she paraphrases here, shortly before he died:

It was October of 1941, I was starting high school in Torre Pellice, where I had been living for six years, with Sisi, in our maternal grandmother’s house. Mostly I was thinking about meeting the boy I was in love with as soon as possible; in a drawer somewhere lay the strange letter from our father that had arrived at the end of July, begging us insistently to help him get out of Riga. He didn’t explain why; he declared that he was sick . . .

Despite her disinterest at the time, her father’s letter contains a line she never forgot: “Because remember that you, too, are Jewish.” Referring to this sentence in the most important letter she would ever receive, she writes, “I can still see it distinctly, word for word.” Jarre’s Jewish identity is part of the book’s exploration; her faith for many years, she writes, wasn’t central to her life. Searching for her father’s grave forces her to confront her relationship with her Jewish faith.

Nonfiction books and especially books in translation frequently immerse us in history and culture that is unknown to us. In Distant Fathers, we learn about the Waldensians, a Protestant offshoot that developed in twelfth century France, whose members lived mainly in the Alpine valleys west of Turin. Here we learn about the Rumbula massacre, as it’s known in Latvia. It’s one of many atrocities that occurred during World War II, but not one many Anglophone readers are likely to know about. Yet the contempt with which Latvian Jews were executed is chilling. The book arguably demands that any effort to move on from this historical period be abandoned—we still don’t know enough.

While Distant Fathers references “fathers,” it’s largely about Jarre’s rapport with the most important women in her life, especially her mother. Jarre recounts how their relationship was quite strained and how she failed to live up to her mother’s expectations. In Return to Latvia, the women from her immediate family fade, while her father is foregrounded. Jarre also logs details about her own genealogical search, reuniting with scattered members of her extended family who share her father’s surname, a history, or both. These details are compelling because Jarre is writing a mystery story that happens to be a memoir. Jarre realizes family is the first and best mystery we encounter in life. Both memoirs also reflect how her life paralleled some of the most salient moments of the twentieth century, including the rise of Mussolini and the expansion of the Nazi empire. In Distant Fathers, she recalled a speech Mussolini gave during the year she turned fifteen. Five years later, when she turned twenty, the Germans finally left her grandparents’ Italian town near Turin. “What are usually called the best years of one’s life are for me contained between those dates,” she writes in Distant Fathers.

Jarre essentially couldn’t escape these parallels, and as such, toward the end of her long writing career, she wrote that first memoir. These historical moments have regrettably left many voids in her family tree. “I hold inside myself the sound of countless voices, voices of those who’ve been dead now for many years,” she writes. They are voices whose stories have largely disappeared.

Not surprisingly, the centerpiece of the memoir is Jarre’s 1999 return to Latvia, following an absence of some sixty years, undertaken to piece together what happened to the father she last saw as a child, and to find his final resting spot. Jarre uses preparations for the trip and post-trip analysis to revisit many aspects of her childhood, and her relationship with her parents. Those readers who have buried a parent, especially a father, will find Jarre’s journey painfully familiar—though it may also be cathartic, retracing the years vicariously. “Of his voice I retain only an echo,” Jarre writes of her father. “I no longer know what name he used when he told me to leave him in peace to read his newspapers.”

Jarre balances such intimate disclosures with historical information not only about the events of 1941, and other war crimes, but also efforts after the war to find war criminals and to make sense of what happened. The crimes themselves—how the mass graves outside of Riga were constructed or how the bodies of the thousands of victims were mercilessly disposed—and the ways in which perpetrators escaped justice for decades never lose their power to shock.

Her memoir occasionally bursts with clear-eyed observations about guilt and blame. To what extent have all the war crimes been examined and resolved? Perhaps a better question: To what extent have the crimes been overlooked? Jarre would be the first to say she, too, moved on with her life; indeed, that’s what makes the letter from her father so painful. But part of the work of piecing together her father’s story is figuring out who did what when. And it’s chilling to learn how often Latvians did the Germans’ dirty work. A cousin writes to Jarre at one point, “If the Latvians hadn’t offered their services as executioners, the situation wouldn’t have become so terrible.”

Nonfiction writers often begin in the present and then work their way back into the past to retrieve the most important moments of their lives—and of their stories. That’s not Jarre’s approach; instead, she tends to circle back to important points. As Goldstein explains in a Translator’s Note in Distant Fathers, “There is very little about the telling that is straightforward.” What’s notable is how her storytelling reproduces her mind’s babel of languages, her complex emotions, the efforts to leave behind the past, only to be drawn again to Riga, 1941. The memoir, after all, pivots around events that transpired more than seventy years before she wrote the book. With some pique, she remarks that she doesn’t even know the Latvian language; her trip literally takes her back to another life that just happened to have been her own.

Jarre, who died in 2016, concludes the memoir with the information she sought about her father’s end—which leads her, poignantly, to beg forgiveness of the man she never stopped mourning. In an age of hypersensitivity to spoiler alerts, I quote from the final section without much worry because nothing can dent its almost cruel power to pierce us as daughters and sons, first and foremost.

I dried my eyes and prayed. So, praying, I asked forgiveness in German, our language, from my father, my Papi, for what they had done to him and for leaving that morning in December, never to return.

What it might have cost Jarre emotionally to face this awful truth, one can only imagine. But we readers are the grateful, if tearful, recipients of this revelatory largesse.

Jeanne Bonner is an editor, essayist, and literary translator. She was a 2022 NEA Literature Fellow in Translation. She teaches courses in writing and Italian part-time.

This post may contain affiliate links.