Eric Van Hoose is a doctoral student at the University of Cincinnati. He writes a monthly column for Full Stop about prisons and popular culture.

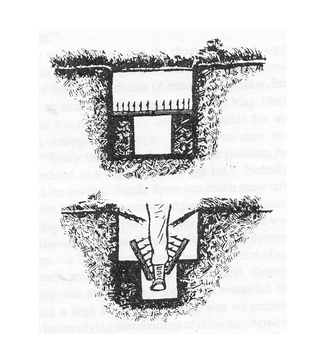

Hostile, defensive, disciplinary. Writers have been using those strong adjectives to describe some of the architecture that has been appearing in cities across the globe and which makes use of spikes, barriers, oddly angled benches, and even sprinklers. The spikes are designed to prevent sitting or lying, the dividers are there to obstruct the free flow of movement, and the benches are angled to make sure you can’t get comfortable enough stay too long. This kind of design is now a part of our malls, our parks, our bus stops, campuses, our neighborhoods, and, in general, our so-called public space. According to a recent article in The Guardian, the “emergence of hostile architecture has its roots in 1990s urban design and public-space management.” And this emergence can be seen, especially in the U.S., as growing in the aftermath of the war on drugs and the culture’s embracement of mass incarceration. It seems that as we became more comfortable locking people away in prisons we also became more comfortable making the everyday environment inhabited by the general public into a private, confining space as well.

The Guardian has published a few stories about this architecture, and the consensus there is that, like most things, this is primarily about business. Business owners don’t want homeless people loitering, sleeping, shitting (or doing anything but making purchases, really), so this architecture is aimed at disciplining the homeless, moving them even further into the margins, so that customers can do their shopping without having to confront the upsetting facts of poverty, homelessness, financial instability . . .

Of course, as Alex Andreou pointed out in February, there’s also an important psychological component at work. He notices that this type of architecture, which he came to experience firsthand after becoming homeless, “speaks volumes about our collective attitude to poverty in general and homelessness in particular. It is the aggregated, concrete, spiked expression of a lack of generosity of spirit.” And he’s certainly right. As he puts it, “Most of us are a couple of pay packets from being insolvent. We despise homeless people for bringing us face to face with that fact.” Yes. Many would rather place reality’s less than pleasant aspects out of sight and out of mind, even if that means building barriers into everyday life. In a way, this architecture is as much about maintaining a certain kind of freedom — a freedom of unawareness, an aesthetic freedom in which there are no desperate people distracting us from the immaculate storefronts, freedom to consume via the proper channels — as it is about limiting other kinds. For many, what some call hostile, defensive, and disciplinary could just as easily be called welcoming (to those of certain classes), offensive (in its ability to preempt the unwanted), encouraging (in its ability to streamline consumption).

No matter how one views it, this architecture is an even larger component of daily life than The Guardian’s limited coverage lets on. Of course, the intent to punish the poor and the homeless spills over and ends up punishing seniors, pregnant women, people with disabilities, as Andreou notes. Of course, it sends large messages to all who encounter it, whether those messages affirm or deny their values and sense of belonging. But the relatively recent examples of this kind of architecture called to our attention in The Guardian account only for a small portion of this kind of architecture. Bullet proof glass has encased gas station clerks and cab drivers for decades. Speed bumps line the streets of impoverished neighborhoods. Subdivisions are gated, adorned with neighborhood watch signs. Surveillance cameras are everywhere. People want to “protect” national borders. These are all part of defensive architecture, too. And of course, even though they’re often intentionally located far from view, we cannot overlook the prisons that dot the landscape of the country and hold nearly one out of every one hundred U.S. citizens in confinement. Spikes in the ground, reminiscent of some grim booby trap, are certainly better at garnering attention and provoking outrage, but these other, often subtler features of our built environment have been around long before the sidewalk spikes, slanted benches, and concrete sprinklers.

Focusing on the most visually arresting examples of hostile architecture distracts us from the other, slier ways mistrust and communal erosion have been built into our lives. While a bullet-proof enclosure might be a reassuring promise of safety for some, it teaches all who see it to be afraid, to expect bullets, to distrust.

And, in the name of expanding this line of thinking even further: the economy is built, too — architected through laws, policies, and practices. Who does it serve to include? Who has the most trouble gaining access to jobs and financial means? So many communities lack access to healthy food, transportation, adequate healthcare, well-staffed and equipped schools, and the kinds of facilities — recreation centers, community centers, centers for the arts — that are so good at bringing people together. As we work to address these problems we might be best served by understanding the connections between the very real physical defenses that are part of our communities and the ways in which more opaque defenses against inclusion are built into our economic system.

How we build our world reflects how we see ourselves and others. Part of what makes this type of architecture so fascinating is that it illustrates our values so literally and concretely. It showcases how those in power envision the world and people’s places within it — and seeing it helps us comprehend the extent to which people will go to influence others in the name of money and comfort.

There are alternatives, though. And while all design is necessarily limiting in some ways, it’s possible to make places that encourage and enhance relationships between people and lead to greater collaboration and communication. The people with real social and economic power are building these kinds of places. The best, most current example is likely Apple Inc’s newest “spaceship” campus, which is one unified, mostly glass circle. In an interview, architect Norman Foster explains that proximity between departments was carefully thought-through: “Of course, you have got an enormous range of skills in this building — from software programmers, from designers, marketing, retail — but you can move vertically in the building as well as horizontally. The proximity, the adjacencies are very, very carefully considered.” It’s clear that the building is designed to play to people’s strengths, to bring people closer together. Imagine if our communities were built with the same logic in mind.

This post may contain affiliate links.