Is a place an object? Is a building? If I cannot go there anymore, have I lost it? Is the experience of loss, in that it is always a losing of some thing, to objectify? If I am lost without it do I become an object myself?

The more I write about objects, the more I feel the need to position myself in relation to them.

My name means “home” in a language that I do not speak. Properly transliterated from the Greek it would be written estia, un-capitalized because it’s a common noun. It also means altar or hearth and therefore radiator and hot plate, it means dormitory and cafeteria or canteen and so, I extrapolate, probably kettle; objects that contain fire, or warmth for the sake of maintaining the conditions necessary for life.

The word that became my name began as that of a deity, far from my home or those of anyone in my family, thousands of years ago in ancient Greece.

I pronounce our name wrong, with a hard Northern European ‘H’ and the emphasis on the wrong syllables. Even so, when travelling in Greece, once introduced, I make friends with ease disproportionate to my foreignness. Greek is a language in which the power to warm the home is inscribed with significance. That which is needed to sustain life and conviviality or to maintain a resting place where we can be safe together is deserving of respect. To be named for a radiator is not a joke, but an honor. I once met a Greek girl, D, whose first word on being introduced to me was “home!” She now lives in the room upstairs from mine.

Estia was a deity who was so essential to everyday reality that she disappeared into it. Her name’s transformation into common noun might be understood as a kind of archetypal narrative of becoming object.

The map is not the territory, the name is not its object and yet the longing to belong exists. If I am to decolonize my longing to belong must I lose everything? Is belonging possession or can we belong to each other?

Is it better to be possessed by every thing than possess any thing?

I love to tend and stare into fires; whether that’s because I was conceived after fire walking or because I was told so or because the fire and I have an innate connection from which “I” came and for which I was named cannot be determined. My parents wanted to name me after a fire goddess, and a nurse in the hospital went home and consulted her copy of The Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology. It was she who found and suggested Hestia as a name for me.

The first place I was home, the place my parents took me home to, did not belong to them but for a while it was in their care, they were its custodians. Years before the place had been given as a gift to someone who had work to do. He and many others, amongst whom were my parents, had been doing that work ever since. Before I was born the community was forced to close by the local authorities, which cited unregulated and therefore supposedly unsafe use of sheds and outbuildings for dwellings as justification for their action. The place lay almost empty except for my parents, and then myself and those who still came when they could, from all the far-flung corners they had spread to. I won’t name or speak for them here — “they” can be such erasure but I am using it here to acknowledge a thousand and one stories, not yet mine to tell — this whole thing was as real for them as it was for me, and we belonged to it, all of us, the work was home.

Hestia Peppe contributes a monthly column for Full Stop of still life writing concerning sugar givers, salt cellars, talismans, fetishes, and transitional objects; an experiment with vanitas not so much as momento mori but as animist memoir.

I was so small and new and the place for me was the whole of my life, until that time was over. Even when my parents bought a house of their own and we moved out, we lived nearby and we came back often, our own house like a satellite to the place where we had come from.

When I was six years old we went further away, for two years we lived on the other side of the world.

He who had been given the place as a gift died young and unexpectedly. At this time my parents and my sister and I were still living far away and he was, with only a few days warning, gone. We couldn’t get back until after the snow of his funeral was long melted. It was summer and the place was still there, and the work was still there, and we stayed for a little while with the others. When the summer ended and many had to go away again we knew there was somewhere to come back to. We carried on for a long time going away and coming back to be together. Twice a year we would gather — those that could — and in between those times there was a constant coming and going. I was still quite small and quite new, but I remember.

With the need to create shelter comes the instinct to defend it. Worse, with the need to define territory and belonging, the definition of property. There is a right-wing newspaper in Greece called Estia. Oikos, another Greek word meaning the domestic, lends itself etymologically to economics and therefore to capitalism and the markets. Patriarchy renders the labor of home-making invisible by reifying it as feminine love and refusing to assign it a financial value. Property development becomes social cleansing and smart homes invite surveillance and social control. As the artist Liliane Lijn has observed, this power that warms the home, that which was once assigned to the archetypal feminine, is now the power of industry, electricity, the potential destroyer of our planet. Belonging, or the need to be at rest on the earth, may not now be easily separated from annihilation.

It seemed to me that the work continued, that the place gave it continuity even after his passing, but I was smaller and newer than some and I didn’t know much of power, or the grief of those who had known him long before I was born.

I don’t like to call him a leader; I think he was an anarchist. His responsibilities were left in the hands of an old friend who had been doing the work with him for her whole life, she got it from her parents. She held that space for fifteen years; for the rest of her life. People kept coming back, some came every year, or twice a year, some only rarely, some of us, who stayed close, came every day, or week, or month.

Ten winters ago, a few months after she too had passed away, they announced their intention to sell the place. In this instance ‘they’ were those that had, however they had gotten it, the power to do so: to sell the place that was a gift. The name we had for it, in yet another language, had meant “shelter-hostel-school carrying on forever.”

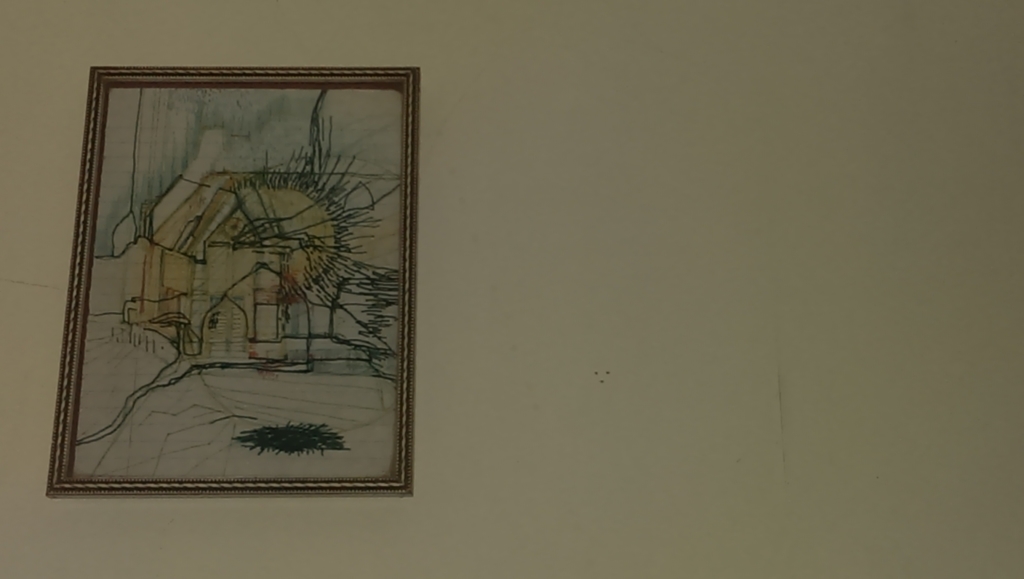

I kept the ashes of the last fire we burned together, stayed up with it, watching until the last flames went out.

In ancient Greece when explorers left to seek new lands or people built new homes, fire was taken from the hearth, the altar to Estia in the old home or the temple in the hometown and with this the new hearth was lit.

I am a small burning ember travelling from one home to the next.

This post may contain affiliate links.