[FSG; 2014]

[FSG; 2014]

Tr. Stanley Chapman

People who’ve seen Darren Aronofksy’s Requiem for a Dream tend to fall into one of two categories: those who have no wish to see it again (either because they disliked it or found it too upsetting), and those who seem to feed on watching it over and over. As one of the latter, the former like to judge me. The best defense I can offer is to call it cathartic, even Greek—an aesthetic cyclone that, despite its shallow characters and unabashed clichés, leaves me cleansed and sated every time. Aristotle argued for tragedy’s purification of pity and fear via dramatic action, embellished language, artistic ornament. In tragedy, characters should bring misfortune on themselves through “some error or frailty.”

In Requiem for a Dream, the embellished language is the cinematic experience; his characters’ error and frailty the most basic of human frailties: overwhelming, crippling desire. In her essay, “The Death of Tragedy,” Susan Sontag defined Oedipus’s tragedy not in terms of “implacable values,” but a situation in which “crisis had overtaken those values. It is not the implacability of ‘values’ which is demonstrated by tragedy, but the implacability of the world. The story of Oedipus is tragic insofar as it exhibits the brute opaqueness of the world, the collision of subjective intention with objective fate.” Aronofsky’s vision of that world is indeed brutal: it offers no explanation, no moralization, as it gleefully crushes his banal placeholders, his stand-ins for characters. Harry, Marion, Tyrone, and Sarah — they could be anyone. They are the everyman and -woman, and their story would be worthless — indeed insufferable — were they not tortured for our cathartic pleasure.

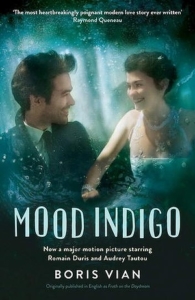

All this I mention as preface to understanding Boris Vian’s Mood Indigo: a strange, singular, and aggressive novel originally published in 1947 as L’Écume des jours. With its dizzying, surrealistic images, its cutting spoonerisms, and aesthetic elevation of pure banality, Vian’s masterpiece is a perfect pairing for Aronofsky’s now-familiar bag of tricks — not to mention one of the few true tragedies (in the orthodox, Aristotelian sense) in modern literature. Its quartet of characters — Colin, the handsome, talented, and rich twenty-something bohemian; Chick, his not-so-rich but equally virtuous best friend; Chloe, Colin’s young, beautiful, and wholly innocent wife; and Alyssum, Chick’s quiet, devoted, and perceptive fiancé — couldn’t be more boring if they tried. For the first third of the novel, Colin is falling in love with Chloe, happily funding their decadent lifestyle with his static, unexplained fortune of “doublezoons.”

Meanwhile, Chick is courting Alyssum, who forgives him his expensive vice — a compulsion to collect every written word, fingerprint, and sweatstain of the pop-philosopher Jean-Pulse Heartre. Vian describes all of this in clichés so sickening it becomes a kind of spectacle. Of Colin: “He was always smiling, as innocently as a baby, and through having done this so often a dimple had grown into his chin”; of Alyssum: “She looked out at the world through wide open blue eyes, and the boundaries of her being were delineated by a skin that was radiant and golden”; and so on. So, too, do Vian’s characters speak in stylistic, absurd clichés: “‘Oh . . .’ protested Colin. ‘Hark at the things he’s say! . . .’”; or, to his live-in cook: “Nicholas . . . if I’m not in love by this evening — really and truly in love — then I’ll start a collection of the works of the Marchioness Thighbone de Mauvoir . . . and see if some of my friend Chick’s luck rubs off on me!”

As in Requiem for a Dream, this vanilla bliss would be meaningless without the obvious, tragic spiral looming ahead of them. Vian peppers this Elysium with small, threatening glimpses of the world in which they live and to which they remain oblivious. As they go for a crisp winter walk, Colin and Chloe pass through a commercial corridor: “In another window a fat man with a butcher’s apron was cutting the throats of little children. It was a display advertising Family Allowances. ‘So that’s where all our money goes,’ said Colin. ‘It must cost a terrible lot to clear that up every evening.’” During their wedding, at the top of a towering cathedral, they hear a “brutally discordant and hopelessly lost chord” from the orchestra: “The conductor, who had taken a step back too near the edge, had just toppled over into space, and the deputy conductor had to take over without a break. At the very moment that the first conductor squashed himself flat on the floor-slabs below, they played another shattering chord to cover the din.” No one, of course, seems to notice.

For their honeymoon, the couple leaves the city. On their way through a copper mine on the outskirts of an industrial zone, they notice “hundreds of men, dressed in goggled dungarees . . . moving around in the flames. Others were stacking up the fuel in regular geometric pyramids . . . Under the effects of the heat, the copper melted and ran in red streams fringed with spongy slag that was as hard as stone.” Chloe is disturbed by the sight, and despite Colin’s reassurance never seems to recover. On their honeymoon — in a drafty old house in the country — she comes down with a cough that sounds, to Colin, “like a rip through a gorgeous piece of wild silk.” Soon after, Chloe is diagnosed: there’s a lily growing in her lung. The only treatment, says her surgeon, is for Colin to surround her with flowers, supposedly to bully the lily into submission. As Colin’s fortune dwindles — spent on hundreds, and then thousands, of flowers — their cushion against the mechanized, violent absurdity of the world thins and ultimately vanishes: there’s nothing to protect them from reality. All that’s missing are the screeching strings of Requiem’s Winter suite, or perhaps the ancient Greek chorus: “Don’t say we didn’t warn you,” etc.

Like all tragedy, Mood Indigo’s energy comes from the disaffected ruthlessness of circumstance. Just as Kafka’s corporate environments are horrifying in their indifference to human depth and emotion, Vian’s modern city is monstrous in its disregard for life. At the factory where Chick is forced to take a job, death is a day-to-day occurrence: “As he left the workshop he stood aside to let the stretcher-bearers pass with the four bodies that they had piled on to a little electric trolley ready to dump them into the main sewer.” Because this happens on Chick’s shift, and because it decreases his department’s productivity, he is fired. “Where’s your sense of justice?” he asks the production manager, to which there’s only one possible response: “Never heard of it . . . Anyway, I’m too busy to waste my time talking to you.” Colin’s attempts at employment fair no better. At an armory, he uses his body heat to grow rifle barrels right out of the ground: “Now you have to make a dozen little holes in the earth,” says his boss. “Then you stretch out on the earth after you’ve stripped. Cover yourself with that sterilized blanket, and do your best to give out a perfectly rectangular heat.” Naturally, when Colin proves unable to grow his quota of weaponry, he is fired.

It’s these scenes of industrial horror, of bloodthirsty greed, that give Mood Indigo its power — and it is powerful. Surprisingly so. Like the Thebes of Oedipus, Colin’s world cannot care what happens to him; and, like Oedipus’s audience, were it not for Colin’s suffering we’d gain nothing from his life: we, too, wouldn’t care. But as the audience, we can see it. We can care, and we do.

This post may contain affiliate links.