In A Lover’s Discourse, among many other figures, Roland Barthes presents us with the figure of the one who waits.

“Am I in love? — Yes, since I’m waiting.”

Anxiously for a telephone call, alone at a café, hovering over her phone for a text message—the lover is the one who waits.

The loved one doesn’t wait because the loved one is loved. By dint of being loved, all actions point towards the loved one; it is impossible for the loved one to wait because the loved one has no idea that any actions are happening at all.

“The other never waits. Sometimes I want to play the part of the one who doesn’t wait; I try to busy myself elsewhere, to arrive late; but I always lose at this game: whatever I do, I find myself there, with nothing to do, punctual, even ahead of time. The lover’s fatal identity is precisely: I am the one who waits.”

As I write this I am in France, in a village an hour outside of Toulouse, where I work at an art program. Because the program is international, and taught in English, my French is poor but improving. My favorite phrase is baise-moi plus fort, which I have only ever uttered in jest and never on duty; I have no reason to say it in seriousness because my own loved one is 3000 miles away. Every day I wake up at 7 or 8 am and walk down a very large hill to where our office and studios are located at the end of a winding road framed by crumbling stone houses and twisty little grapevines, fig trees, roses, poppies, et cetera.

I am also writing letters.

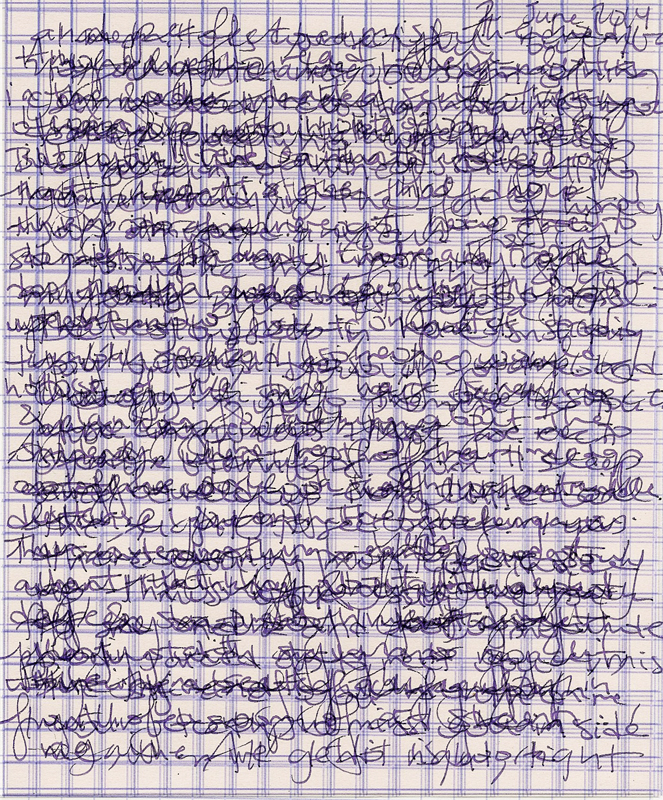

The bulk of my day is spent in an office, when I’m not making rounds in the studio. At the desk I manage money and handle various affairs between the university, the town, the students, and all that. But in my dull moments, which are some of my finest, I write dirty love letters to my boyfriend, in purple ink on very small sheets of squared paper, stacking pages next to filed receipts and a desk calendar. It’s perhaps not the best use of my postage petty cash: I’m working! I’m in France! Why the love letters? Shouldn’t there be more to write home about: describe my days, the sun rising over the river, the way the light falls over the vineyards and the aspens, the cheese I eat or the red wine I drink?

But after all, what is the point of travel writing if not to make you feel as though you are right here, with me? What is the point of food writing if not to make you feel as though you were eating this thing too, or are maybe even the thing that I am eating? In my mouth, et cetera. The love letter, drafted at my desk in this sunny room in southern France; the entreaty, “wish you were here” shorthand for “come here” shorthand for “come,” if not here, then anywhere will do, provided you are thinking of me, which you are, always, because you are expecting my letters.

Like Barthes’s waiting figure, I too have always wanted to be the one who doesn’t wait. I am a consummate lover in that I am always the one who waits: at airports, at coffee shops, on stoops waiting for the loved one to throw their set of keys down. I send text messages, hit send, recoil as it zips across to the loved one, wait patiently for a response, which may yet take hours. So now that I am in southern France, what excruciating waiting must I be doing! There is no texting internationally across six time zones; all I can do is write letters.

Love letters are the least personal thing one can make and the most self-indulgent. Unlike sexts (private, pithy, save a leak) we hope to write love letters so beautiful and disgusting that we would want them to be seen by everyone, who in turn marvel at our wordplay, our wit, our filth, our charm. It matters that they are addressed to the loved one only because we are sentimental creatures; Her’s Theodore Twombly wrote love letters for everyone and anyone at beautifulhandwrittenletters.com. And I’m certain they were received by the unknowing loved ones in just the same way.

By now we are all familiar with James Joyce’s love letters, which are of the filthiest order and which I consulted before writing my own; and who found those? Who published them? I write each letter back to les Etats-Unis secretly hoping that when I die it will end up in a book, although then again, I hope that when I die many things of mine will end up in books.

The love letter as a literary form is showy, a poetic declaration, an unfurling of all the reasons and hows and ways and why. Its response, should there be one, is almost irrelevant: it is impossible to see the loved one read it; sometimes, the exchange is not even published, just the one-sided litany of “me” fucking “you” here, here, or here, outside of space and time. And when posted internationally—a week’s waiting for delivery, maybe more—it becomes an inversion of Barthes’ lover-as-one-who-waits.

“I create and re-create it over and over, starting from my capacity to love, starting from my need for it: the other comes here where I am waiting, here where I have already created him/her. And if the other does not come, I hallucinate the other: waiting is a delirium.”

Once I send the love letter, I no longer wait. The writing of the letter is enough to expend the energy of long-distance loving. The letter is the self-indulgence, the flourish, look how much I love you. The kind of people who write love letters—letters, not texts or sexts or emails—do not, perhaps, even require a response. I am not expecting my loved one to write back: it would be another week before I saw it. I would forget my original letter entirely. Anyhow, I am the writer, not he. And how time passes by! I am content to write letters. My letters are so literary, so poetic that they become one-sided, devotional; they fulfill my desire to be the one who doesn’t wait by hallucinating the loved one into being. Given my distance from the loved one, the literary hand becomes the new loved and lover, which I can marvel at as I seal envelopes and lick stamps before placing these missives in the post.

The lover sends the love letter internationally, paying postage. As far as the lover is concerned, the loved one exists, hypothetically, at a distance; the lover writes the love letters for herself, the lover. The loved one is constructed in the frame of the love letter, the literary thing, the beautiful, dirty object: light as paper, airy as script, posted and sent into the ether, perhaps delivered.

This post may contain affiliate links.