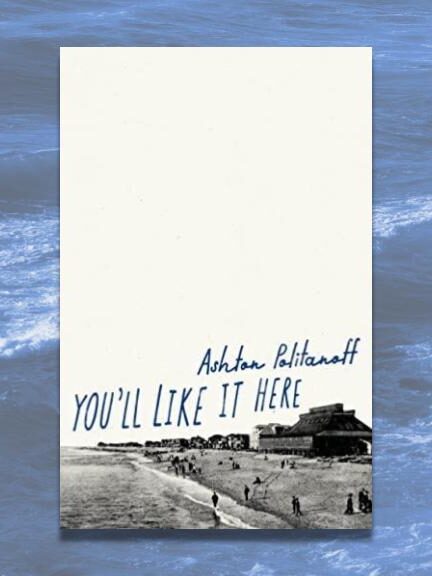

[Dalkey Archive Press; 2022]

The introduction to You’ll Like It Here, the first book by Ashton Politanoff, is three short paragraphs. It explains the author’s relationship to Redondo Beach, where this book is set and where the author has lived for nearly all his life. He states the impetus for the book, writing, “(M)y mother died . . . I found myself searching for old photographs of Redondo in the Redondo Beach digital archives.”

The form of the book is deliberately fragmentary. It is sectioned into three parts, named simply “1,” “11,” and “111.” It is distinctly non-narrative. When glancing through, the reader sees sometimes a few lines, sometimes a few paragraphs, occasionally a few pages of writing, interspersed with black and white photographs of Redondo Beach from the first two decades of the twentieth century. The writings are clippings from local newspapers, modified to suit the author’s needs (in other words, fictionalized). They form a history of sorts of Redondo Beach, California, during the same period. Politanoff said he focused on 1911 through 1918 because, as he explains in the introduction, “I saw a town come to life and recognized an era strangely analogous to our own.”

What follows is a combination of seemingly mundane, but often not, local happenings and my favorite aspect, home and property advice. On page 50, we see a photo of the town, all flat lines and endless sky, a few low buildings and a handful of people in the street. It is a photo that in its lack of anything “special” shows the ghostly materialized, the past in its simplicity, a place barely born. Empty space is significant. Tiny bits of life are interspersed in the air and land, like a garden newly planted. Next to the photo, on page 51, is a news item, “Stroke of Luck”:

A woman and a child were thrown from a light wagon Wednesday at the junction of Pacific and Catalina Avenues. The wagon struck a hitch in the road and the woman in the rear fell to the ground. The wagon wheels passed across her chest . . . no serious injuries were documented.

I am touched by how the clipping’s main characters are a mother and child, and how she escaped danger. And yet. Everything eventually goes away, including our mothers and wagons. A lovely one-sentence entry called “Egg Stains on Silk” reads, “Rub gently with a cloth and ordinary table salt.” Ordinary life continues to need to be taken care of, despite being punctuated by larger events.

What I love about the housework entries is really just this: Housework and childcare are what I have done with most of my life, hour-wise. It is barely considered a thing anymore. But without it, we would live in squalor. It surely isn’t in our daily news anymore, that I’m aware of. And yet, the homes that women made and people continue to make are where our childhoods take place. Our homes, where we grew up, are the important and deep roots of our lives, soon overtaken by time. Replaced, even. But, as made clear by the similarities of this documentation, the past does indeed repeat itself.

More specifically, much has been written and documented about the Gold Rush and subsequent populating of California. The great promise of this western state was and remains a dream, a lure. Joni Mitchell sang of it, Led Zeppelin as well. To this day, people move to California in hopes of fortune and freedom and the beauty, albeit not for gold. The myth is strong, largely because of its roots.

Roots. They can be ripped out, when needed. There are new beginnings. And what is lost becomes a memory. Then, excavation is necessary to some. To Politanoff, for sure.

In the latter part of the novel, World War One begins and the flu epidemic rages on. The entries show the fear and warnings and efforts to manage these terrible events. Here is where the book’s subject matter most obviously echoes our current time. But, to me, they also often echo all times. One entry called “The Deplorable State of Our Boys” is about young men doing young man things. In short, rebelling. Specifically, thieving and desecrating graves. Food shortages ensue, and an entry called “Mask Shortage” is pointedly relevant to our world now. The plague, the Spanish Flu, is very much like our plague now. For example, the entry “Swift Response” is about the closing of public spaces, stating, “. . . trespassing individuals will be forced to quarantine a home.” It ends with the claim that “Dr. Norvill expects the epidemic will be short-lived.” Storms rage and cause destruction and death.

Toward the end, fear and loss become more poignant. With this comes nostalgia, which often gets a bad rap. I found a few definitions that are of interest. One is “a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.” This is sort of an upbeat version, but language is malleable, and many people think of nostalgia as a bad thing. Merriam-Webster defines it as “a wistful or excessively (italics mine) sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.” Here, nostalgia is defined as too much sentiment, too much yearning. Merriam-Webster continues with a second entry, simply: “HOMESICK.” Doesn’t nostalgia then just mean, “I miss you?” And perhaps some people miss others too much, but who is anyone to say what too much is?

There are moments of such longing in this book. In its physical presentation, it immediately reminded me of Roland Barthes’s Mourning Diary, which he wrote after his mother died. Barthes’s book is just that: diary entries. In this way, the content differs. But the physical structural similarity—short, non-narrative entries on each page—and the desires of the authors to make sense of an incredible loss, are comparable. How to process a great loss? Other than to write, to excavate our feelings and their lives?

Two entries toward the end are placed very well. The ending of You’ll Like It Here is very strong in that the ubiquitous sadness of nostalgia is tempered with other human characteristics—hope and something that feels like love, even if it’s just the memory of love. One is called “How To Live.” The other is “A Watched Pot Never Boils.” The former begins with the sentence “One percent of people today know how to truly live.” From there, the paragraph lists what the other ninety-nine percent choose to suffer, including “bad air, improper posture” and “constipation.” It is a humorous entry, and indicative of nostalgia turning into a disgust with the now. In “A Watched Pot Never Boils,” a man writes in the first person a beautiful and (for this book) long description of his heart beating dangerously and his subsequent loving care by his wife:

She had me sit down again and slipped a handkerchief of wrapped amyl nitrite under my nose. Breathe, she said. Then she unlaced my coltskins, removed my wool socks, and ran a hot bath . . . For the first time in a long while, I listened to her tell me about her upbringing, and felt my chest relax.

Of interest to me is that in many ways, the short “chapters” and the non-narrative aspect of this book are very much fashionable now, evoking a sort of “flash fiction” that was brought on by the internet, and historically can further be traced to writers in the 70s, like Richard Brautigan and Jayne Ann Phillips. Even Hemingway dabbled in this structure, the paragraph story. But what makes You’ll Like It Here different is the author taking a trending formal structure and turning it on its head. It looks back in its subject matter, and its wistfulness honors that past. As Politanoff projects his loss and himself into seemingly obscure, old news items of Redondo Beach, a reader always does some projecting as well. In this way, the writer and the reader actively approach the text. The loss of a parent is felt in the mundane details of the lives briefly illustrated here, which awaken nostalgia in the words and realities and memories that haunt the physical world of the past. As a result, You’ll Like it Here is a worthy, unconventional entry into the genre of elegy.

Paula Bomer is the author of the novels, Tante Eva and Nine Months, the story collections, Baby and Inside Madeleine, the latter of which the New York Times called “raw,” stating it as “the rare book for which the word seems truly warranted.” She is also the author of the essay collection, Mystery and Mortality. A new essay collection is forthcoming from Publishing Genius in 2023, and she is at work on a new novel. Bomer has lived in Brooklyn for over thirty years.

This post may contain affiliate links.