Over the course of the past few weeks, I’ve seen the same viral image shared across several different social media platforms. The photograph in question is a tight shot of a handwritten sign, presumably in a café, which reads: “No ‘Wifi’ . . . Talk to eachother [sic]. Call your mom. Pretend it is 1993. LIVE.” While I won’t expound on the irony of an anti-internet sign garnering attention through the very medium it sets out to chastise, I will, if you’ll indulge me, challenge the writer’s questionable sense of nostalgia — which I assume is a pining, not specifically for Doc Martens and Meg Ryan comedies, but merely for simpler times, unimpeded by the distractions of modern technology. If that’s the case, then I’d like to adjust the wayback machine slightly, and pretend it’s 1923 instead, an age where “Apache” was a dance and the only password you needed to remember was the one that got you through the backdoor of a speakeasy.

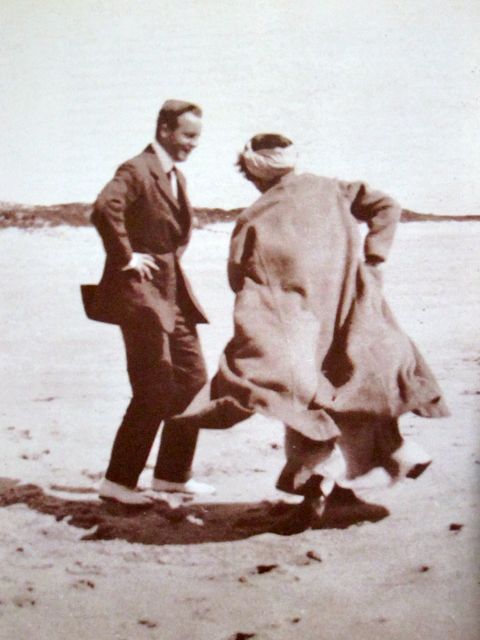

On June 13th of that year, Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Les Noces premiered in Paris. Like most opening nights, the performance was followed by a celebration, in this instance, a grand soirée on a Seine river barge, hosted by Gerald and Sara Murphy. For those not familiar, the Murphys were a pair of wealthy American madcaps, who were best known amongst the “Lost Generation” set for being legendary party hosts. Though artists in their own right, the Murphys more or less earned their places in history by entertaining the likes of Man Ray, Dorothy Parker, Ernest Hemingway, and the Fitzgeralds. On this particular night, the guest list included (to name a few) Cole Porter, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Tristan Tzara, and naturally, Stravinsky, who, according to biographer Amanda Vaill, skipped cocktails and went below deck to rearrange the place cards.

Sara Murphy decorated the tables with piles of tin cars, dolls, and plush toys, which Picasso formed into absurdist tableaus. Everyone drank bucket-loads of champagne, and Cocteau shuffled around the boat, clutching a lantern and shouting “We’re sinking!” In a fashion slightly evocative of Gatsby’s Klipspringer, pianist Marcelle Meyer appeared and serenaded the guests with her rendition of Scarlatti’s sonatas, and ballerinas danced. Finally, as author John Richardson wrote in his book on Picasso: “As dawn broke, [Boris] Kochno and [Ernest] Ansermet . . . took down the gigantic laurel wreath, inscribed “Les Noces — Hommages,” which Sara had put up in the main saloon, and held it like a hoop for Stravinsky to take a running jump through.” To this day, the gala is regarded as one of the most off-the-hook parties in history, cementing Gerald and Sara Murphy as an iconic “it-couple.”

So why do I bring this up? Because apart from the wild parties, Gerald and Sara Murphy are also famous for being the inspiration behind Dick and Nicole Diver, the alluring but emotionally insolvent protagonists of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night, a novel that is, if nothing else, a tale of detachment and marital loneliness. The book is rife with comments about how alone Dick and Nicole feel in one another’s company (and with friends and lovers, to boot). In one scene, in which the pair sits in frosty silence, Fitzgerald notes how Dick “often felt lonely with [Nicole],” and in another, he describes Nicole as “leading a lonely life, owning Dick, who did not want to be owned.” Most poignantly, in Chapter 12, Fitzgerald writes: ” . . . they sat with the children on the Moorish roof and watched the fireworks of two casinos, far apart, far down on the shore. It was lonely and sad to be so empty-hearted toward each other.”

How much of this sentiment is based upon impressions of the Murphys versus Fitzgerald’s own fractured relationship with Zelda is difficult to say, but the point still stands that in the literary imagination of the Jazz Age, people who engage in the most public, grandiose acts of socialization (what our sign writer might consider to be living), are the ones who are the most isolated from real human interaction. This is certainly a prevalent theme in The Great Gatsby, where lavish, glamorous parties — undoubtedly influenced to some degree by those thrown by the Murphys — are portrayed as the ultimate symbol of social disengagement. Gatsby is as alone at his parties as he is in death, and that goes for anyone and everyone else. As Ronald Berman says in his book Fitzgerald’s Mentors: Edmund Wilson, H.L. Mencken, and Gerald Murphy:

A [Fitzgerald] story like “Jacob’s Ladder” will show the lonely crowd — people always en masse — while other works like “May Day” show people connected only by the moment. In The Great Gatsby . . . [people] are briefly seen (often in a stunning, objectified evocation of appearance or dress or manner) and soon gone.

This concept of parties equating detachment is not limited to Fitzgerald, either. Joseph Moncure March’s 1928 narrative poem novella, The Wild Party, passes a similar judgment on its characters, who all engage in an orgy together without ever developing more than a superficial interest in one another. By the time things at this grungy, Manhattan pleasure party are wrapping up, March writes, “Their voices wailed from quavering throats/and clung fondly to the long, sad notes/they swayed/leaned back/closed their eyes/in sour attempts to harmonize.” In other words, making a concerted effort to interact with others does not necessarily equate making a meaningful connection.

The Murphys avoided the cruel oblivion that befell F. Scott Fitzgerald towards the end of his life (supposedly, Sara was actually one of the few people to attend Scott’s funeral), but the tragedy of losing a son in 1935 prompted Gerald to write in a letter to Scott: “I know now what you said in Tender in the Night is true. Only the invented part of life — the unreal part — has had any scheme, any beauty. Life itself has stepped in now and blundered, scarred and destroyed.” So excuse me, sign writer, if I find your directive to turn off my laptop, imagine I’ve gone back in time, and “live” to be little bit overblown and condescending. If you want to throw wild parties on the Seine, be my guest, but I’m probably just going to hang out here and watch Netflix.

This post may contain affiliate links.