The Frieze Art Fair in London, like Art Basel or TEFAF, is one of those little whirling eddies in space and time where normal, established categories seem to fall apart. Art and money, commercialism and culture, the beautiful and the faecal — all these things usually held to be opposite poles locked in an antagonistic contradiction suddenly become indistinguishable. Given all this, weaker and more directly experiential aspects of life are all but defenceless. Sound, for instance: strange things happen to sound in the Frieze Art Fair. It’s very much a fair rather than a gallery, and the big white tent pitched in Regent’s Park inspires none of the subdued shuffling dignity of a museum exhibition. Instead the sounds of scraping heels and clinking glasses blend into the muffled chatter of four thousand people under the broad echo chamber of its roof. When it rains — and this being London in late autumn, of course it rains — its patter sounds like a rolling wave of white noise washing across the entire space, something you could at first confuse for an abstract sound sculpture. The few windows are tinted, and the outside world glows in a restricted palette of broodingly apocalyptic greys and greens; it’s not hard to imagine the rainwater lifting the entire fair from its moorings and carrying it out to sea on a swollen Thames like a Noah’s Ark of art. It’s all quite distracting, but that’s not a bad thing at all.

This isn’t a place for viewing art; it’s a place for selling it. Its spatial logic has nothing to do with the gallery but follows the paradigms laid down by shopping malls: big, brightly lit spaces, walkways, a few hubs for seating, a market-stall arrangement, and plenty of dining options for weary shoppers. This being an art fair, it’s a little more upscale than the usual Zizzi or Pret A Manger; at one end of the exhibition there’s an outlet of the Michelin-starred Locanda Locatelli restaurant, radiating the smells of updated Italian home cooking and the sounds of clipped, monied conversation as if to taunt hungry and impoverished journalists. In each gallery’s stall the various pieces are displayed according to the best practices of consumer retail, with big signature artworks placed prominently to draw in the buyer’s attention and artificial plywood crannies huddled in corners to arouse curiosity. Most prominently, the inherently confusing spatiality of the shopping mall is replicated. These places are intended to keep you wandering for as long as possible. They use slight angles and occasional islands and deceptively simplistic maps. The point isn’t to aid navigation but to actively impede it, until after a while you feel like you’ve been trapped in some ironic hell of soft white lighting and beckoning shop fronts. Stay in those places for too long and you can start to understand why so many suicides and spree killings take place in malls.

All this seems less jarring in the main Frieze London space. Most of the works there have been created under the prevailing conditions of artistic commodification, and this is exactly where they belong. This time around, though, the main space has been joined by Frieze Masters, in which works from the dawn of the image to the turn of the third millennium are shown and sold. There’s something downright weird about seeing the same marketing techniques applied to Inuit carvings, Renaissance masters and Spatialist austerity. But despite this weirdness, there’s something interesting — and encouraging — going on.

The museum-form, in which we’re used to approaching these artefacts, imposes a blanket aestheticization on art. This isn’t always a good thing: once disruptive or political artworks enter the museum-space they’re immediately stripped of their broader significance and turned into objects of pure aesthetic contemplation, smothered by their own auras. By forming a heterotopia solely dedicated to art and the ultimate fetish-object of “culture” the museum robs individual works of their ability to refer to anything outside this bracketed space. A while ago I saw an exhibition at LACMA in Los Angeles of the revolutionary Chicano collective ASCO; pieces like Gronk’s incredibly visceral The Truth Of The Repression In Chile were being reverentially appraised by comfortable bourgeois types with their lips pursed and their hands clasped behind their backs. They’d been calmly and viciously neutered. Art fairs do something very different: by imposing the logic of exchange onto the work of art they actually manage to open it up to other uses.

In Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he argues that the ability for images to be reproduced exactly robs them of their aura or cultic value — the “here and now of the work of art, its unique existence in the place where it is at this moment.” It is this aura of genuineness that ties an artwork to its own tradition and that makes it an object of reverence. Once an image can be duplicated, the notion of a genuine original begins to fall apart. However, Benjamin doesn’t lament the loss of artistic aura — he embraces it, writing that “the instant the criterion of genuineness in art production failed, the entire social function of art underwent an upheaval. Rather than being underpinned by ritual, it came to be underpinned by a different practice: politics.” The means of mechanical reproduction that Benjamin describes are photography and cinema, both technologies that were still in their relative infancy in the 1930s. Now, there is no single image of everything. With the widespread use of mobile phone cameras, any image is reproduced and transmitted an infinity of times. And there are plenty of mobile phone cameras at Frieze. While many galleries and museums still ban photography, at Frieze it’s almost encouraged. After all, you have to know what you’re purchasing. An object for sale in a market stall (in a world configured like a market) can’t make the same claim to inviolable uniqueness as one in the set-aside space of gallery. Buyers and students walk past exhibits snapping away at everything in sight, and some works even directly encourage it. Jennifer Rubell’s self-portrait, for instance, takes the form of an enormous reclining sculpture, pregnant and nude, with a belly you can crawl into and curl up inside, positively begging you to get a snap of yourself Engaged In Dialogue With Art.

The question raised by these art fairs is: who is the consumer of art? The exhibition is open to the public (if you can fork out for the hefty entrance fee), but it has little to do with the democratic and socialist mass art that Benjamin envisaged as a result of emergent technologies of duplication. The fair is organized around the needs of a small art-buying elite for whom the artwork exists as a signal of social and cultural status or a stable repository for economic capital. Its entire point is to promote the idea of a unique and genuine work whose physical embeddedness in space and tradition justifies its price tag. Much of art criticism has given up on theorizing art in favour of justifying it. At the same time, there’s a remarkable dissolution of cultic value. One stand at Frieze Masters proudly exhibits Brueghel’s The Census at Bethlehem; there’s very little indication that the painting on show isn’t the 1566 original, but a copy by the Flemish master’s son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Some art critics have upbraided the fair for displaying “fakes,” but none of the viewers seemed to mind. Their phone screens flickered constantly in the darkened stall: it’s the image itself that matters. When the image is fungible and exchangeable, the fact that the actual painting itself is soon to be sold to some oil billionaire is almost irrelevant. The phone camera actively disrupts the elite’s claim to “own” art — it belongs to anyone who can take a photo of it.

Of course, the mobile phone camera doesn’t reproduce its object exactly. The sense of scale is lost, along with the texture of the paint and the interaction between light and color; the whole thing becomes flattened, a smooth plane beneath a flat screen. Viewing art through the screen of a phone also involves a kind of distracted distancing, a lack of total immersion in the piece itself. This isn’t necessarily a negative phenomenon: Benjamin describes lucidly the political importance of mass distraction in cinema:

The ability to master certain tasks in a state of distraction proves that their solution has become a matter of habit. Distraction as provided by art presents a covert control of the extent to which new tasks have become soluble by apperception. Since, moreover, individuals are tempted to avoid such tasks, art will tackle the most difficult and most important ones where it is able to mobilize the masses. Today it does so in the film. Reception in a state of distraction, which is increasing noticeably in all fields of art and is symptomatic of profound changes in apperception, finds in the film its true means of exercise. The film with its shock effect meets this mode of reception halfway. The film makes the cult value recede into the background not only by putting the public in the position of the critic, but also by the fact that at the movies this position requires no attention. The public is an examiner, but an absent-minded one.

Something similar is happening to painting at Frieze. Art is liberated from its own context. Flying through the interfaces of a million handheld screens, it takes its place among the innumerable other electronic representations that swarm across the planet and radiate out into space. There are, of course, some rearguard actions on the part of the art industry. One of the most prominent is the otherwise baffling recent trend of displaying mirrors as artworks. By literally reflecting their surroundings, these restore some sense of rootedness; meanwhile any picture you take of them will just be another selfie. In galleries these are always distinguished by the small crowd that tends to form in front of them, pretending to consider its implications while actually briefly checking their hairlines and making sure they don’t have anything stuck in their teeth. (They’re also notable for the ingenuity of the explanatory cards displayed next to them; various mirrors can apparently trouble notions of space, sitedness, individual identity, creativity, or, of course, art itself.) At Frieze, they’re everywhere. Probably conscious that once taken home and hung on someone’s wall a simple mirror’s value will tend to drop quite sharply, sellers are now showing tinted mirrors, mirrors in unusual shapes, mirrored cubes hanging from the ceiling. It’s unlikely to stave off the phone-camera revolution for too long. As ever, capital creates the conditions for its own overthrow. Something new and powerful is being built here that could soon discard the art fair itself as a useless husk: the radical commons of the image.

PS: The object of the art fair is to render aesthetic value and exchange value indistinguishable. In this it’s a spectacular failure. Still, there are plenty of people who bemoan the effect all this money is having on the quality of art. I’d suggest that they’re not properly applying dialectic principles to this opposition. As Freud knew, money is intimately connected with shit, but then the creative artistic act is also fundamentally anal. The two are joined at the hip, or more properly, at the arse. It’s also worth remembering that wherever the money-form has arisen, currency has always been in the form of those commodities that have no practical use except for their beauty and those used to adorn the body: precious metals, beads, shells, and so on. Meanwhile, painters and sculptors have always worked with the basest materials: mud, clay, blood, faeces. It’s not the case that worldly money corrupts the “higher” form of art; art tends to corrupt money’s pretensions with its own baseness. And it seems to be winning.

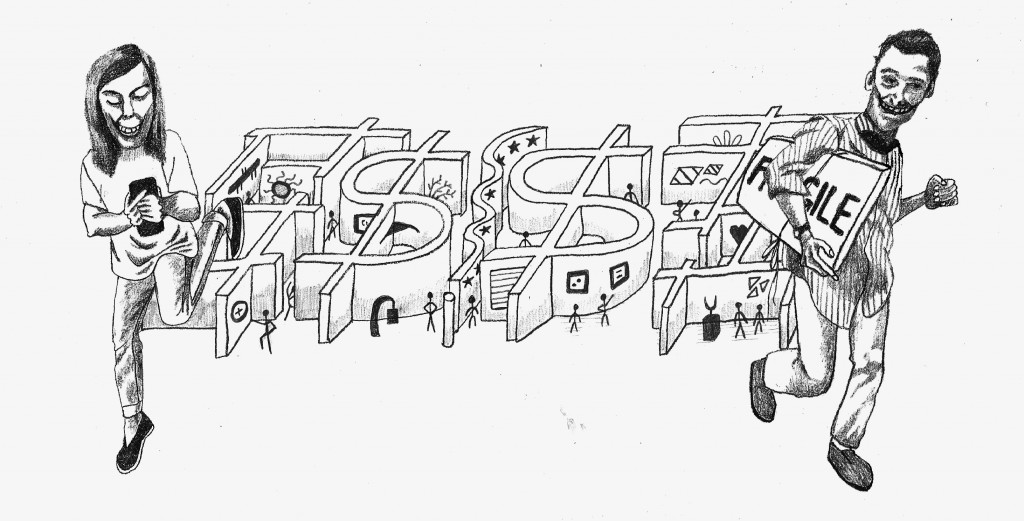

Illustration by Eliza Koch. See more of Eliza’s work here.

This post may contain affiliate links.