At a screening this summer of Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, the film’s director David Lowery told the audience that he wasn’t going to be specific about when his movie was set, because he was aiming instead more for “a feeling, than a time.” The film, a beautifully shot but ultimately boring sequence of good-looking people speaking only a few words in a “once upon a time in Texas” scenario, left me mostly bitter — I felt something, maybe. Mostly I was upset that the film thought it was so much deeper than it was, all because it had the right look, because it had that cloying soundtrack, because the filmmakers obviously had said, “Yes, we’ve struck on something real, and beautiful, and all about America here.” It was lazy, but even worse, it was manipulative at the expense of trying anything difficult. The crowd gave it a standing ovation.

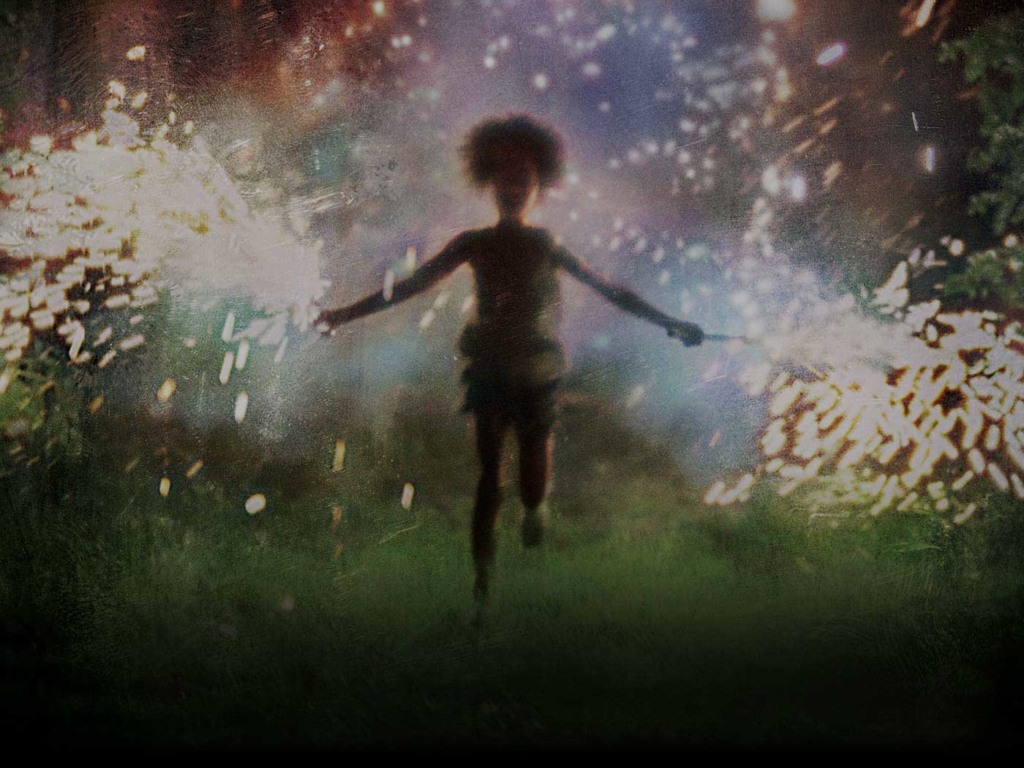

Last month there was a long essay that made one very good point: smarm (or as it’s usually called — middlebrow) can be incredibly reductive. Some middlebrow works have now rejected any attempt at complexity, aiming only to get as much “feeling” out of the viewer or reader as possible. In films and novels this new form of middlebrow can be seen in some well-known works, mostly by young white guys couching a manipulative and unrealistic dynamic in a recognizable tragedy. All of Jonathan Safran-Foer’s fiction work, as well as the 2012 film Beasts of the Southern Wild, are guilty of not actually offering anything complex, just something simple and easy and, well, smarmy. They say, “Despite 9/11, Holocaust, Katrina, there’s still some beauty out there.” They make you think you’ve actually had a thoughtful exercise, while not actually asking the reader or viewer to ponder anything difficult at all.

These works all aspire to something higher and more meaningful as they leave you sobbing on the floor (for a sympathetic character has died!), but as the great critic Dwight Macdonald so elegantly put it in his essay “Masscult & Midcult,” their way of working “pretends to respect the standards of high culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them.” The best works are now the ones that make you feel the most, the ones with that great soaring score, the ones with the tragedy, and not the ones that make you think anything besides “beauty, sadness, beauty.” They try to win your heart with a light dose of melancholy.

We can probably blame this all on Days of Heaven. Terrence Malick’s shortest film, its value really lies in the beauty of its shots, its oblique narration, its reminiscence of a time most Americans never thought existed. Walking away from the film, as the young orphan runs off on yet another adventure, probably to die penniless in the American West, the viewer feels much the same way as when viewing works of the new smarmy middlebrow: “Yes, that was depressing, but so much beauty, huh?” But even Malick grew tired of that simple trick (so tired, he took 20 years off). When he returned with The Thin Red Line, gone were the meditations on becoming a mud doctor, solemnly replaced with long monologues about lives wasted for no reason, about an unimpeachable evil that could not be overcome by any means.

This year’s To The Wonder was one of his most complex and honest works to date. Critically and commercially it failed, however, because it never attempted to deliver anything simple to the audience. In the final lines of his final review, Roger Ebert wrote, “There will be many who find ‘To the Wonder’ elusive and too effervescent. They’ll be dissatisfied by a film that would rather evoke than supply. I understand that, and I think Terrence Malick does, too. But here he has attempted to reach more deeply than that: to reach beneath the surface, and find the soul in need.”

The new works of smarm, or middlebrow, or whatever, just like the old ones, are so eager to supply, to please, that they are practically begging: “Please feel,” they implore, as if emotions were a difficult thing to conjure.

This post may contain affiliate links.