When Chiyoko, whose husband has been replaced by ill-intentioned lookalike Hirosuke, is brought to the titular location in The Strange Tale of Panorama Island, she is so overwhelmed by the artificially constructed place’s surreal hedonism that she faints.

It’s unlikely that this graphic novel by Suehiro Maruo, adapted from Edogawa Rampo’s 1926 novel of the same name, will cause anything approaching such a strong response. While the graphic novel — or, more accurately, the manga — is a fairly direct adaptation, the material is hardly as shocking as it may have been at its original publication. The times have changed, of course — what might have been daring or scandalous in 1920s Japan is generally palatable in 2013 America — but Maruo, known for his transgressive, disturbing comics, passes on the opportunity to match Rampo’s baroque flourishes with modern outrages and plays things surprisingly safe.

The original novel (recently released in its first English language edition by the University of Hawaii Press) was a relatively early-career work by the progenitor of Japanese mystery/detective/weird fiction Rampo (born Tarō Hirai, his pen name honors Edgar Allan Poe; roll Poe’s name around in your mouth and it’s not hard to transform it into “Edogawa Rampo”). In it, floundering writer Hitomi Hirosuke seizes an opportunity when he hears that Genzaburo Komoda, his college classmate and spitting image, has died. Hirosuke steals Komoda’s identity, pretending he was only comatose, and seizes the Komoda family wealth. He uses the fortune to transform a sparsely inhabited island into a garden of delights that conforms to his every whim, which, befitting someone compelled to literally reshape the world to meet his innermost desires, are pretty strange.

The panorama of the book’s title and the island’s name refers to an entertainment that was briefly popular in late-nineteenth century Japan (after earlier popularity in the U.S. and elsewhere). Panoramas were round buildings large enough to accommodate dozens. Visitors entered through a dark tunnel and seemingly emerged into another world. They stood on a raised, circular platform in the center of a room. On all sides, the walls of the panorama were painted to reproduce a scene — famous events from history, beautiful vistas — with statues and decorations added to cause the viewer to feel that they had stepped fully into the world depicted.

The panoramas immersed viewers in experiences, and served as refuges from the increasing clamor and crowding of Japanese cities moving into the 20th century. Panoramas were a haven from encroaching modernity. In them, “the observers enjoyed a sense of visual power and control they could never hope to experience while being swallowed up in, distracted, and consumed by the busy, noisy, confusing metropolises in which they lived,” according Elaine Kazu Gerbert’s introduction to the University of Hawaii edition of Panorama Island.

While Hirosuke’s panorama stretches the idea of an encompassing, artificial world across an entire island, it’s far from anti-modern. Rather, it’s defined by its modernity. To fund its construction, Hirosuke sells the Komoda family brick-making business, noting that brick construction is outmoded and will soon be replaced by concrete. Though it seems like a pastoral retreat, there’s a huge network of dynamos and engines on the island, described by Hirosuke (in Maruo’s version) as “dream machines that produce nothing.” This network of machinery that literally serves no purpose prefigures the alienating, mass-manufactured world of the mid-20th century (to say nothing of the current workplace in which, for many of us, our voluminous keystrokes produce nothing tangible). The sense of power Gerbert describes viewers having while inside a panorama is surely something Hirosuke craves, but his panorama isn’t a refuge from the confusion of modern life for anyone but him.

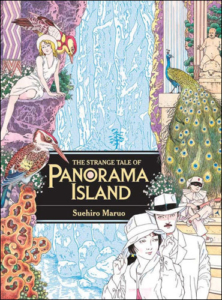

On the basis of his work, and the visual extravagances described in the novel, Maruo seems like the perfect interpreter for Rampo’s book. Maruo’s comics are cult works, sparsely available in English (out of dozens of manga, only Ultra-Gash Inferno and Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freakshow have previously been available), which feature extreme gore, explicit sex, disturbing compulsions, and bizarre horror. Despite those subjects, Maruo’s work retains a compelling and artful quality in even his most body-fluid-soaked work. The strangeness of his ideas and his recurring tropes (military insignia, schoolboy uniforms, eyes, furtive sex) are clearly the work of an artist with a singular vision. His nuanced art demonstrates strong draftsmanship, a tight command of anatomy, and innovative page designs. A skilled artist with such an unbounded imagination seems perfect to realize Rampo’s debauched Island.

But if you enter Panorama Island expecting Maruo’s traditional excesses, you’ll be disappointed. For the first half of the story, before Hirosuke and Chiyoko visit the island, he seems restrained, perhaps to highlight how unmoored and hyperbolic the island is compared to the characters’ quotidian lives. On the island, there’s a lot of sex, some of it graphic, but Maruo’s adaptation reveals none of the nightmarish vibrancy present in his earlier works.

That’s not to say that Maruo doesn’t imprint himself on the manga. His cleverness as an artist shines through in many places. In comics, each panel represents a frozen moment of action. For example, if a ball is being thrown, the first panel may show the thrower pulling back her arm, the second following through and launching the ball, the third the ball reaching its destination. Maruo, however, freezes multiple instances of movement in the same panel. Instead of depicting the movement of an arm across three panels, Maruo draws a single panel with the arm in all three locations simultaneously, making the character appear to have three arms. Another panel shows Hirosuke rising from his pillow, his head in three positions giving him the appearance of a three-headed man. This sort of formal flourish is jarring and creepy. In the time that it takes to parse the image, a gust of uncertain reality makes everything grotesque — fitting for Rampo’s sensibility.

Maruo’s artistry also allows him to provocatively expand on the original novel’s themes of developing modernity. For instance, Chiyoko’s distress stems from a distinctly modern problem: the sense of being too observed. Eyes are a visual motif throughout the book (and Maruo’s work generally; you’ve never seen so many — or perhaps any — eyeballs licked sexually as in his comics). In The Strange Tale of Panorama Island, Maruo’s motif takes on heightened significance. As Hirosuke and Chiyoko enter the island via a clear undersea tube, Maruo arranges tiny fish to appear like sets of eyes lurking in the dark water. Later, the giant feathers of a peacock are dotted with eyes. The island is thick with statues, all of which seem to leer at Chiyoko. In our YouTube age, being seen isn’t shocking — judging by reality TV and social media, not being seen is more terrifying — but when motion pictures were just 30 years old and photography barely more than 50, it’s easy to understand feeling queasy and disturbed at the revelation of this panopticon. Chiyoko seems particularly unsettled because she isn’t the viewer; instead, she’s part of the panorama, forced into playing a dehumanized role similar to a statue.

Maruo’s work also derives strength from its visual nature when illustrating the tension between modernity and tradition that the panorama — both the exhibit and the island of the story — embodies. For instance, in more than one scene, 30-something Hirosuke wears a modern suit while negotiating business deals with kimono-clad, middle-aged men. This costuming choice more effectively conveys, in just a few panels, the liminal state of the 1920s Japan in which the story occurs than pages of description would.

Despite these effects, a fundamental problem of both the novel and the manga prevents modern readers from truly sympathizing with the characters’ experience of the island: neither written descriptions nor drawings can replicate being immersed in Hirosuke’s twisted imagination. The experience of climbing a staircase that appears to be hundreds of feet tall, but is in fact only dozens thanks to an optical illusion, may be surreal in description or drawing, but reading about it can’t duplicate the experience of climbing it. Riding through a lake on the back of a woman dressed as a swan may be odd, but imagine pressing your thighs into her sides for support. The reader may be unable to fully understand the strangeness at hand, but Maruo creates images strange enough. Even without his standard shock and ugh, Panorama Island is packed with arresting visuals.

Both the novel and the manga end on a note of sour unreality. Once Hirosuke becomes ensconced in his dream island, Rampo’s recurring detective Kogorō Akechi appears almost literally out of nowhere (before entering his first panel, Akechi hasn’t even been mentioned) to rein in Hirosuke. It may be fitting that a story so concerned with Hirosuke’s jarring, artificial creations would end with a deus ex machina, but it’s abrupt and unsatisfying.

Ultimately, Suehiro Maruo’s The Strange Tale of Panorama Island realizes the themes of developing modernity and the dislocation of over-observation in richer ways than the novel. At the same time, it removes elements, such as Hirosuke’s implied sexual inadequacy in comparison to Komoda, which added psychological richness to the novel. Even if we aren’t treated (subjected?) to much of Maruo’s nightmare-born imagery, it doesn’t much matter. His formal flourishes are exciting and his rendering of the sybaritic island gorgeous — and, as with Rampo’s writings, there’s such a paucity of Maruo’s work available in English that anything new is a treat.

This post may contain affiliate links.