There might be something preferable in memorializing someone six months after his death. One hopes that eulogies will be more clear-eyed and composed with more reflection, if not necessarily more critical. I’m not sure if that was why Birkbeck College, University of London decided to hold a memorial service yesterday for Eric Hobsbawm, the great historian and former Birkbeck professor and president who died last October. But the memorial service, held in the academic heart of London, was tear-free.

There might be something preferable in memorializing someone six months after his death. One hopes that eulogies will be more clear-eyed and composed with more reflection, if not necessarily more critical. I’m not sure if that was why Birkbeck College, University of London decided to hold a memorial service yesterday for Eric Hobsbawm, the great historian and former Birkbeck professor and president who died last October. But the memorial service, held in the academic heart of London, was tear-free.

Over the course of two hours, friends, colleagues, comrades and former students paraded across the small stage painting in their eulogies a portrait of a man who will clearly be missed by many. Hobsbawm was famous as a historian and widely popular around the world with people of all political persuasions, the rare Marxist who receives a complimentary obituary from The Economist. He came to communism as a Jew living in Vienna in the 1930s. He’s best known for his trilogy on the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism, but he was a prolific, versartile writer. He contributed op-eds to The Guardian, essays to the London Review of Books and, for a while, served as jazz critic for The New Statesman. His history books, and his essays, are easy and enjoyable reading.

Italian President Girogio Napolitano sent in a pre-recorded video. Neal Ascherson, a Scottish journalist and former Hobsbawm pupil, recounted lessons in morals as well as history. As a young student at Cambridge and recent veteran of the Royal Marines, the professor told Ascherson to be ashamed of wearing a medal he received for his service in putting down an anti-colonial uprising in Malayasia. “He made me think about what I’d been doing and for that I’ll be eternally grateful,” Ascherson said. Martin Jacques, the former editor of Marxism Today, delivered a political biography, tracing Hobsbawm’s politics from the time of Hitler to the time of Thatcher.

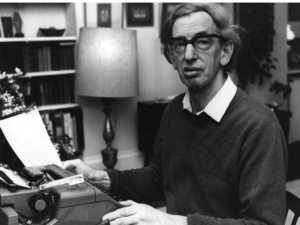

But what I found most interesting in the portrait of Hobsbawm that emerged was not that he was a great teacher (unsurprising), or a great writer (obvious to anyone who has read him), or a committed Marxist (well known), but that he resembled an archetypal bourgeois public intellectual. From the photographs of him in a cardigan and oversized glasses, to the hobbies of birdwatching and jazz, Hobsbawm was something of a stereotype, though not a malevolent one. He was a wide reader and deep thinker. He kept friendships mostly with writers and other intellectuals. He enjoyed the trappings of a comfortable middle class lifestyle. The art historian Simon Schama peppered his eulogy with references to French restaurants and fancy hotels, allusions lost on me, if not most of the crowd. Schama recounted a dinner party at which the “historian from below” found himself seated between Benazir Bhutto and David Frost.

The writer Claire Tomalin, who was tasked with discussing Hobsbawm “as a friend,” talked about these apparent contradictions the most lucidly. Tomalin recounted going to visit Hobsbawm for the first time at his home in Hampstead, a picturesque, leafy North London neighborhood with some of the city’s most expensive real estate. “I asked Eric how being a communist fit with this,” Tomalin recalled. “He said, ‘If you’re in a ship that’s going down, you might as well travel first class.’”

This post may contain affiliate links.