What was most surprising about the response to Beck’s Song Reader wasn’t what people were saying, but who was talking about it. I shouldn’t have to remind you who Beck Hansen is, or why publications like Rolling Stone and Spin would be discussing his latest release. But beyond the music world, Song Reader was also discussed in a literary context: in The Millions, for example — or Full Stop. But even more surprising is how it was lauded as a marketing coup in Forbes, or the discussion of its aesthetic appeal in art-making circles.

So what is it?

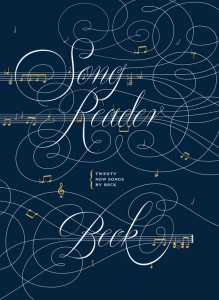

Quite simply, Song Reader is an exquisitely packaged portfolio of sheet music. The songs, which number 20 in total, are a sort of Tin Pan Alley pastiche, with titles and lyrics that contain parodically whimsical references to images and sentiments that can safely be labeled nostalgic, though Song Reader itself is not. Here are some other things Song Reader is not: it’s not recorded music for you to passively enjoy. It’s not an album. And it’s not a book in any traditional sense. I’m inclined to think that it’s not some sort of anti-technology statement, either, considering that part of the project is a website where people can upload videos of their own versions of the songs.

It seems, though, that it might be most productive to define Song Reader not by what it is or is not, but by what it can do. So how do we use it?

Most obviously, we can look at it. The book itself is beautiful. The cover was designed by noted typographer Jessica Hische and is composed of elegant swirls on a rich blue background. The songs themselves are printed on individual sheets that are adorned with throwback artwork from the days of take-it-home-and-play-it-yourself sheet music distribution. There are images of lone women wandering through graveyards, or of a wolf standing on a moonlit hill. There’s an antique camera floating away on water. There are even fake early twentieth-century advertisements. The advertisements are pleasantly cheeky and well-rendered. While falling short of lending a sense of historical authenticity to the project, they signal an alliance with the era being evoked and seem more natural and less gimmicky than might be supposed. Song Reader is, above all else, an object — the artwork is as essential to the success of the project as the printed notes.

You can also play the songs yourself. If you’re a poor reader of music, the songs will probably be fairly difficult to play. If you’re a professional musician, they will probably be easier than a lot of what you encounter. If all you know how to read are guitar tabs, you can probably power through some passable versions of the songs. Releasing music in standard notation, instead of as an .mp3, does seem, at first glance, to be less democratic. (You might especially feel this way if you can’t read music.) But without an officially released “Beck version” of these songs, there’s no authoritative standard version to compare them to.

In a way, Beck is showing us how arbitrary those official versions can be in the first place. Through its seeming arcane fussiness, Song Reader presents a way for music to be more free. And people do seem to be taking advantage of that freedom. You can hear the songs performed on the official Song Reader website, on YouTube, by the Portland Cello Project, and even by staff members of The New Yorker. Of course, you can get almost anything on sheet music, play it yourself, and upload the video somewhere. But by not releasing an “official” recorded version of these songs (at least not yet), Beck has forced a dynamic into existence — an interplay between musicians and listeners akin to what the Grateful Dead achieved. It’s a more balanced relationship between art and community.

The critical response to Song Reader has been mixed, though mostly positive. It’s been called visionary as well as a lazy throwback. Some have even reduced it to Beck giving a middle finger to mp3 pirates. (How would one pirate Song Reader? Use a Xerox machine?) But I disagree. Simply put, it’s a thought-provoking use of the best parts of the internet and print.

Song Reader has found a creative way of bypassing some of the more crass aspects of musical commerce, and I think that’s where the “gimmick” feelings comes from. We’re so used to dealing with art as product that when we’re allowed to share and explore it together as a community removed from the marketplace (even by just one step), our cynicism kicks in. The problem isn’t Song Reader; the problem is us. As one of the song titles intones, DONT ACT LIKE YOUR HEART ISN’T HARD.

This post may contain affiliate links.