I live in Indian country. Well, to be accurate, everyone in North America lives in Indian country. What I mean is that I live in one of the parts that still has actual Indians living in it.

I live in Indian country. Well, to be accurate, everyone in North America lives in Indian country. What I mean is that I live in one of the parts that still has actual Indians living in it.

I grew up in Mississauga, a city west of Toronto, ironically named for the tribe that once lived there. I was told as a child that they were extinct. I’ve recently learned that they were actually pushed to sell their land to the Crown, to make room for incoming colonists, and were forced to relocate. In any case, extinct or simply shoved out of the way, I never laid eyes on a native person, an “Indian,” until I was well into adulthood.

Here on the West Coast, it’s different. This is Nuu-chah-nulth territory, and there are lots of Nuu-chah-nulth people around, living both on the reserves and in the towns. The “Indians” I learned about as a child seemed mythical: elusive as fairies, capable and all-knowing like superheroes, and nearly magical in their ability to slip silently through the landscape. The real Indians, though — the ones I know now — are my friends and neighbors, even an ex-boyfriend.

So what’s that got to do with anything? The thing is, when you think of Indians as something of the past, and perhaps not quite as real people at all (since you’ve never actually gotten to know one) it can be hard to understand where they are coming from. Then suddenly something pops up: the Red Power occupation of Alcatraz Island from 1969 to 1971; the violent Oka land dispute between the Mohawk people and a small town in Québec, in 1990; or, in recent months, the movement known as Idle No More (#IdleNoMore).

It’s easy to wonder: Well, what’s this about? What do they want this time? And anyway, wasn’t this all settled a long time ago?

Well, no it wasn’t. A lot of what Idle No More is about is outstanding treaty issues. In some regions, treaties were signed between the indigenous people and the government, but the government has not kept its part of the agreement. In other regions, treaties have still never even been negotiated or signed at all; some sort of agreement needs to be made.

Although Idle No More started as a grassroots movement in Canada, the issues at its heart affect indigenous people across North America, and indeed in many other parts of the world. For example, in 1868, the U.S. Government signed a peace treaty with the Lakota Nation, guaranteeing the Black Hills as native land. Less than a decade later (following the discovery of “gold in them thar hills”) the government reneged on that agreement. The Lakota are still pushing them to honor it.

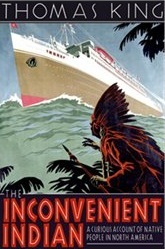

There is a lot of history — a lot of history — that has never made its way into the history books. So it’s very timely that a book by a dual American/Canadian scholar, who is part Cherokee, has appeared. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, by Thomas King, was published in November — just as the first peeps about Idle No More were threading their way around Twitter.

The Inconvenient Indian is a history of both the contacts and the contracts made between the settlers of North America and their descendents and the indigenous people. Thomas King is the first to admit that, as a history, his book is not complete — nor is it even balanced or unbiased. But it does at least fill in some of the gaps that our other incomplete and biased history books have left out.

So, for anyone who has been wondering what the current state of native unrest is all about, you need to look back. The Inconvenient Indian is a good way to start.

This post may contain affiliate links.