People like to talk about what they like, writers especially; stereotypically lonely people, inside they are devoted fan boys and fan girls who’ve found a number of ways to worship their idols in print. The novels of Jonathan Lethem and Michael Chabon are peopled with characters who share the tastes of Jonathan Lethem and Michael Chabon. Books like Joanna Scott’s Arrogance, a portrait of Egon Shiele told through various fictional perspectives, and Geoff Dyer’s improvisational ode to jazz, But Beautiful, are both successful by the virtuosity of their prose and originality of their approaches. And then there are monuments like Bruce Duffy’s historically-rooted The World As I Found It, the biographical novel about Wittgenstein, whose life and world is so fully-imagined in the book that it isn’t important to readers where Duffy draws the line between fact and fiction.

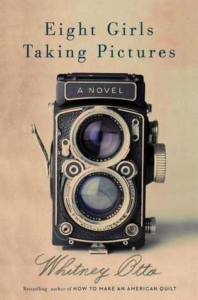

Whitney Otto’s new novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures is a different breed still; a combination attempt at a crowd-pleaser and an homage. The novel tells the story of eight female photographers, in eight different chapter/stories, inspired by the lives of real photographers. In her Author’s Note, Otto leaves the list incomplete, but she includes Imogen Cunningham, Madame Yevonde, Tina Modotti, Lee Miller, Grete Stern, and Ruth Orkin. Each chapter is introduced by a playing-card-sized photo by the spotlighted artist, and the photograph’s true title, meant to evoke a little “ooh” moment when readers get to the scene where the picture is snapped. But the photographers-as-characters are given fictional names; Lee Miller is Ellen “Lenny” Van Pelt, Imogen Cunningham is Cymbeline Kelley, Man Ray makes a cameo as someone called Tin Type, although Hannah Hoch and Diane Arbus, who are only mentioned by the characters, are allowed their real names. The “rules” of Otto’s semi-fiction don’t feel firmly established, but perhaps that’s ok; perhaps this isn’t that sort of book. It’s the sort of book you buy for your mom because she loved Otto’s 1992 bestseller, How to Make an American Quilt (at least the film version—she can’t actually remember if she even read the book-book) and because Monet is her favorite painter and Beethoven is her favorite composer, and you want to give her a little cultural boost, just one rung up the ladder, and yet you don’t want to frighten her with anything that looks intimidating, or too much like a book about “art.”

Following the text Otto writes, “This novel is my love letter, my mash note, my valentine to these women photographers, whom I have loved for most of my adult life.” The line feels almost like a disclaimer or a request for pardon: read kindly, please! It’s about something I really, really care about! By about chapter three, the disclaimer makes sense. Eight Girls can’t quite carry its own weight without the prop of Otto’s personal endorsement. The settings are set by long lists of New York’s noises and Mexico City’s smells that seem to have come from a creative writing classroom exercise, and the romance—the dangerous eyes and coy dialogue—is unimaginative at best, corny at worst. While Otto asks us not to take the stories for biographies, many of the chapters work to contain the entire arc of an artist’s life within the space of forty pages. The emphasis is on the girl over the pictures in the book, and the particular dilemmas that come to women artists, particularly the question of what to do about the kids:

“This was her paradox: She wanted to be in two places at once, to be two people at the same time. If she could split herself, one Miri would be happy spending all day with her toddling children with no thought about doing anything else . . . Her other self would be making movies with David. Or possibly taking pictures on her own, with no lingering regret about not having children, or not being home with her children.”

But this paradox, like the book’s other conflicts—the Holocaust, say, or sexually abusive fathers, or money—stops short of ever feeling quite real because the characters themselves never feel quite real. There are so many of them, with so much family baggage, so many backstories, and so many friends, that the girls begin to blend into one Everygirl; gamine, smartly dressed, familiarly discontented, and Otto shies away from getting under their surfaces. Perhaps most frustratingly, the structure of the book does nothing to capture the feeling of photography; the stories lack both the focus and concentrated emotion of a good picture. Cumulatively, the stories link together into a sprawly narrative. In a whirlwind of spectacle, we travel from San Francisco to Berlin to South America to London, while the girls flirt with surrealists, pose nude for Diego Rivera, talk about the Bauhaus, bathe in Hitler’s tub. The last two chapters are Otto’s best efforts in the book, but by that point, the novel has the effect of a too-long made-for-TV-miniseries.

At times I felt sympathetic toward Otto, who seems in over her head—it’s difficult to write a love letter! And when the addressed is someone as cool and beautiful and traumatized as Lee Miller! I saw the fiction writer Kevin Brockmeier read once, and afterwards, he sat at the signing table offering lists of favorites—photocopies of Brockmeier’s fifty favorite short stories, fifty books, fifty films, to anyone who was interested. At the time I was perplexed by this, and put off; but now I see the bravery in those lists, which make no effort to explain or qualify or embellish the good things they contain. He simply wanted to share those objects with the world, but not at the expense of messing them up. I don’t want to say that Eight Girls has ruined these photographers for me, but by the end of the book, they’re obscure to me now, they’ve become half-people, cardboard stand-ins. The shame is that the next time I see an Imogen Cunningham photo, I’m afraid I’ll see it in a different light, through the haze of Otto’s mediocre story-telling.

This post may contain affiliate links.