One of the more interesting aspects of American culture is how deeply wedded innocence and violence are. The radiance of our culture shines in a complacent and mindless cheeriness over the entire world. Think of our saccharine pop music, our amusement parks, our elevation of youth to a nearly moral condition.

One of the more interesting aspects of American culture is how deeply wedded innocence and violence are. The radiance of our culture shines in a complacent and mindless cheeriness over the entire world. Think of our saccharine pop music, our amusement parks, our elevation of youth to a nearly moral condition.

But just as prevalent, and definitely more profound, is our national penchant for pairing the gum-drop with the blood-stained. You can’t think of the summer of love without thinking of Manson. You think of the jet-setting smooth jazz of the sixties and realize that it’s chained, somehow, to the lynchings and church bombings of the South. The glitzy fun of disco humming along inside of decaying and crime-riddled cities. David Lynch’s pristine American suburbs, where one day you find a human ear in a field and the trap door opens under you, revealing a shadow world of drugs, violence, and insanity that had always been there, waiting for you.

In the collective myths of our past we try especially hard to cover up the ugly side of our national character. The American Prairie, breadbasket of our continent and epicenter of plainspoken American purity, is a sort of “safe space” in our cultural memory. The hardworking, plainspoken and resilient men building their own personal paradises alongside the hardy and simple women is an archetype that we desperately cling to. Like all pasts, it’s an idealized one. Perhaps it’s most fully realized literary manifestation is in the Little House on the Prairie books, in which Laura Ingalls Wilder describes a painfully simple pioneer culture of Sunday school and log cabins. If that were our only artifact from the time and place — 19th-century Kansas — the nostalgia would be heavy and inescapable, like a black hole from which neither doubt nor complexity can escape. Forget the fields of rotting Buffalo corpses, ghost towns, and Indian villages wrecked by disease. Forget the lawlessness, the murderers, the rapists, the lynchings, and the starvation. But those things were real, too.

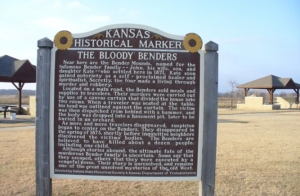

There’s no better example of how inseparable American dreams of a pristine past and American nightmares of domestic violence than the tale of the Bender family. The Bloody Benders, as they were known, are as deeply woven into the fabric of American identity as sports, jazz, drug wars, highways, and labor strikes. It’s the story of how a disturbed family ran a bed and breakfast almost solely for the purpose of finding fresh murder victims. Theirs is the story of the domestication of violence, of how the dark and malevolent is less likely to exist in the grimace of some supervillain in a top hat, and more in the strange smell coming from your neighbors’ basement. Just seventeen miles south of Independence, where Wilder and her family all wished each other good night before bedding down in the evenings, was the town of Osage, the home of the Benders. John Sr. rarely spoke. He wore a heavy beard and had the face of someone who almost never smiled. His wife, known simply as Ma, was the bitter matriarch of the clan, having such a sour disposition that she was known as “She-Devil” to the locals. The parents rarely interacted with other townspeople, leaving their children to act as social ambassadors. Daughter Kate fancied herself a psychic healer and attended church regularly with her brother, John Jr. They were by most initial accounts a normal, if exceedingly private, immigrant family of either German or Dutch origin, running a B&B out of the front of their large cabin and farm compound. Except for prickly attitudes, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Sure, there were some locals who had disappeared mysteriously, but there wasn’t enough evidence to point a finger at the Benders.

Until Dr. William York went missing. York had set out in search of another missing man, who had left with his daughter to build a new life near Osage, never to be found again. The thing that made William York’s case different was that his brother was a Kansas state senator, the kind of person with the resources to launch a proper search and investigation. After a woman fled the Bender cabin, claiming that Ma Bender threatened her with knives, York arrived with an armed search party. There was a back and forth, with Ma Bender claiming that the woman was a witch who had poisoned her coffee, and Kate Bender offering to help use her psychic powers to help York find his brother. Everyone in the search party thought they were guilty and wanted to hang them on the spot. York demanded that they acquire proof.

More locals went missing, prompting a town meeting where it was decided that every local home would be searched. By the time the Benders were to be searched, it was noticed that their livestock were unfed. Their field, it was also noted, was always plowed, but never seeded. The Bender family had silently slipped away from Osage.

A search of their property confirmed what the search party had suspected. There were over twelve bodies found on the property, one of them being in the well. William York was found buried in the orchard. There were body parts barely hidden everywhere, nearly all of them with their heads bashed in and throats cut. Not all of them were in one piece. Apparently the M.O. of the Benders was to set up a sheet behind visiting guests, hit them over the head with a hammer, then have one of the lady Benders jump on them, finishing them off with a slash across the neck.

It’s a very grim, very American story. Even more so because of its ending: the Benders escaped. Some reports had them splitting up, taking different trains East and West. They went down to Mexico. They rode to St. Louis and blended in. They recreated themselves in Michigan. They made it to New York, continuing their spree hidden in the urban sprawl of the growing metropolis. They returned to Europe, to regather their strength and wait for everyone to forget. They moved west to California, making a fortune speculating in some young and vital industry. They got stronger. They lost their accents. They are the strangers who just moved in next door, who invite you over to dinner with an awkward smile. They’re the neighbors you’ve known for years, the ones who are always gardening at odd hours. They’re your friends. They’re your coworkers. They’re you. The dual nature of American daydream and violence always has loose ends that tease our imaginations, dispersing a fear so general, so diffuse, that it’s nearly identical as a legend to the happy myths that we tell ourselves. You can’t have Wilder without the Benders.

This post may contain affiliate links.