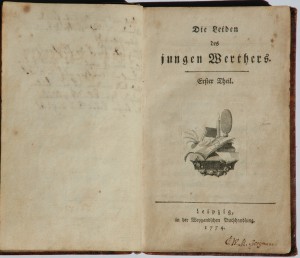

Near the end of the 18th century, the first Italian translation of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther arrived in Milan. But they never reached the shelves of Milan’s burgeoning bourgeoisie: the copies were bought up by the Catholic clergy and burnt. The reputation of Goethe’s Sturm und Drang masterpiece had preceded it, having already unleashed a mimetic wave across Germanophone Europe. Young men had taken to wearing the protagonist’s blue tailcoat and yellow waistcoast, adapted his manner of speech, and, more chillingly, imitated Werther’s final act of suicide. The rash of suicides so worried authorities in Milan, Leipzig, and Copenhagen that the scandalous novel was banned in each principality; years later, the American sociologist David Phillips coined the term “the Werther effect” to describe art’s power to inspire violence.

Even before so many young Prussian gentlemen ended their own lives, artistic influence had been problematic for society. The problem traces back to the roots of Western philosophy — Plato himself bans poets from his ideal city out of concern for their subversive powers. Every act of censorship is a tacit admission that the artistic sublime is a double-edged sword — for all the technical mastery and innovation in the films of Leni Riefenstahl, they cannot be separated from the ideology which they served so effectively.

This menacing interplay between art and reality is, if anything, of even more importance in a culture so thoroughly inundated with images as our own. Yet the question only comes to the fore rarely — and then only as a moral escape hatch — through which we shove social ills to reassure ourselves that evil is not a social phenomenon. Consider the aftermath to the 1999 Columbine massacre, when the arbiters of conventional wisdom sought recourse to the killers’ love of video games and heavy metal as an explanation for the unexplainable. Art can be censored when dangerous; people never should be. Reality, however, is never so simple. It was the supposedly demonic Marilyn Manson who, in Michael Moore’s documentary Bowling for Columbine, displayed a stunning pathos when asked what he would have told the two young men he apparently inspired to commit evil: “I wouldn’t say a single word to them. I would listen to what they have to say and that’s what no one did.”

After another horrible shooting at the Aurora, Colorado midnight showing of The Dark Knight Rises, it is little consolation that this time around there are fewer fingers being pointed at art’s supposedly malign influence and more at a toxic society that does little to defuse anger, aid the mentally afflicted, or address its gun fetish. Nevertheless, there are disturbing details, such as the fact that many in the audience failed to register the horror unfolding, believing it instead to be a particularly effective trick from director Christopher Nolan. Naturally, this caused some to wonder if the shooter, who according to various reports either identified himself as the Joker or was wearing a mask like the movie’s villain, took his cues from Nolan’s unremittingly dark takes on Batman.

But to the extent that Nolan’s films were discounted as an inspiration for the massacre last Friday, we may finally be learning something about art. If Nolan’s films are violent — they are, but not especially so — it’s because the tastes of the viewing public increasingly skew towards the beautiful, chaotic panoramas of a Nolan or Michael Bay blockbuster. Art does not, despite its occasional pretensions to the contrary, dwell wholly apart from society at large, and cannot bring in any corruption that was not already latent. The young men of Germany who killed themselves two hundred years ago may have taken a cue from Werther, but the despair on which they were acting was their own. The fault never lies so heavily with art as it does within ourselves.

This post may contain affiliate links.