Tr. from Spanish by Rosalind Harvey and Anne McLean

History repeats itself.

Everything has been done before.

There are only seven original plotlines.

To the stymied scholar, these platitudes can be liberating — we need only look to the past to find our footing. To the aimless artist, they can be damning — we are forever caught in a washing machine on endless rinse cycle. And yet, as Beckett says: “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

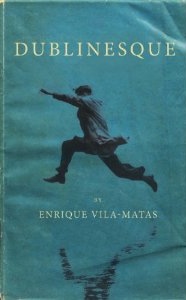

This is the how I visualize Samuel Riba, the purposeless protagonist of Dublinesque, written by Enrique Vila-Matas and translated by Rosalind Harvey and Anne McLean. Though he might not agree with that washing machine business, Riba would certainly appreciate my ostentatious use of quotation: Vila-Matas inserts us firmly inside Riba’s head for a majority of the novel, and Riba can barely squeeze out a thought without invoking the works of Shakespeare, Paul Auster, Tom Waits, David Cronenberg, and even Coldplay. He lives obliviously in the shadow of his influences and seems quite self-contented with the burden of the Over-Educated Man.

Riba predominantly concerns himself with the death of literature’s influence in the world. He is a veteran publisher who, strangely enough, wishes to have a funeral for books — the dramatic irony of it all is that he doesn’t realize these books are traitors who have killed all of his own original thoughts or ideas. Indeed, this novel is rife with such dramatic irony; although Vila-Matas never strays from Riba’s perspective, he seems to whisper bitchily to the reader throughout about Riba’s complete lack of self-awareness: Look at him!, he seems to say, Just a wayward sneaker clunking away in the spin cycle of life! And he has no clue! Riba also remains unaware of how absurd he is in his contradictions: he laments the replacement of Gutenberg with Google, even though he prefers to participate (however guiltily) in the Google era. His wife despairs at how much time he spends on the computer, shut up in his room, and his parents constantly pester him about his upcoming projects. Samuel Riba still has all the problems of a petulant teenager even at 60, and the reader cannot escape his infuriating lack of motivation to change.

Riba even fears leaving Barcelona, though he has long wished to travel to Dublin or London. Although he immerses himself in English poetry and song lyrics, he still cannot speak or understand the language. His fear cripples him until a dream of Dublin and the incipience of Bloomsday (June 16, the infamous date depicted in Joyce’s Ulysses) finally incites him to go on that long-awaited trip.

*****

The narrative trudges up to this turning point, upon which both Riba and the unflagging reader expect immense transformation. But the trip passes, Riba returns home, and nothing much has changed: “the moon shone, having no alternative, of the nothing new.” How could we have been fooled into expecting anything other than the Beckettian quotidian? “This will have been another happy day!” The sun still rises on Beckett’s Winnie. Vila-Matas’ Riba still whiles away his hours in front of the computer screen, and cannot have a single thought without putting it in quotations.

However, there is one subtle shade of change: in the aftermath of his uneventful trip, Riba feels himself vaguely haunted by the young Samuel Beckett—or rather, a young man in a trench coat he sees looming around Dublin who everyone believes is the spitting image of a young Beckett. This young man also resembles the mysterious figure that lingers on the periphery of Paddy Dignam’s funeral in the Hades chapter of Ulysses, who Nabokov purported to be James Joyce himself. At the funeral, Leopold Bloom is thus confronted with his own author. Riba, ever wishing to emulate his literary heroes, suspects that this young man who looks like Beckett is his own author, a higher power he can rely on for guidance. This suspicion gives Riba instant relief and acts as a spiritual crutch; perhaps, with this author, he will not fall to the clutches of alcoholism again. Perhaps his wife won’t leave him as he fears. Perhaps everything will turn out just fine and he will never have to change his ways.

It is both shocking and gratifying for the reader, then, when the narrative stutters into first person, just once, for the slightest moment: “—forgive the interruption, I do need to distance myself somewhat, but if I don’t say it I’ll burst out laughing—”. See there!, cries the reader, The author! Peeking out from his natural habitat! Up until this point, Vila-Matas has opted to use the third-person, which immediately distances us — we feel as if an intruder has inserted us inside Riba’s mind. But can we cry out to Riba and tell him he was right after all? God doesn’t make it that easy — so why should Vila-Matas?

This one vital moment sent my mind reeling off into the existential stratosphere where Riba dared not go: if Vila-Matas is Riba’s author, is he also the mysterious man from Dublin? And, in a case of dramatic irony for Vila-Matas himself, do the translators Harvey and McLean add even another layer of surveillance to Riba’s fate as they manipulate his thoughts into English, an unfamiliar language? Dublinesque offers the reader layer upon layer of secrets that only she is privy to, and the effect (as it often is, when one is the sole owner of a secret) is thrilling.

But poor, unknowing Riba should not fear — if Beckett tells us anything, it is that life will go on much the same, even without a higher power for guidance, even without his wife, even if tempted by drink. And if Vila-Matas tells us anything, it is if RIba can’t go on, his books, a poem, or the lyrics of a Coldplay song will help him go on.

This post may contain affiliate links.