A motherboard circuit is the center of a computer, like a brain stem within the PC body. On Macs it is called a logic board, and four weeks ago it was the failure of this function inside my laptop that resulted in the loss — the death — of an unsaved, near-complete review of Tan Lin’s The Patio and The Index, a miniature book recently published online at Triple Canopy.

A motherboard circuit is the center of a computer, like a brain stem within the PC body. On Macs it is called a logic board, and four weeks ago it was the failure of this function inside my laptop that resulted in the loss — the death — of an unsaved, near-complete review of Tan Lin’s The Patio and The Index, a miniature book recently published online at Triple Canopy.

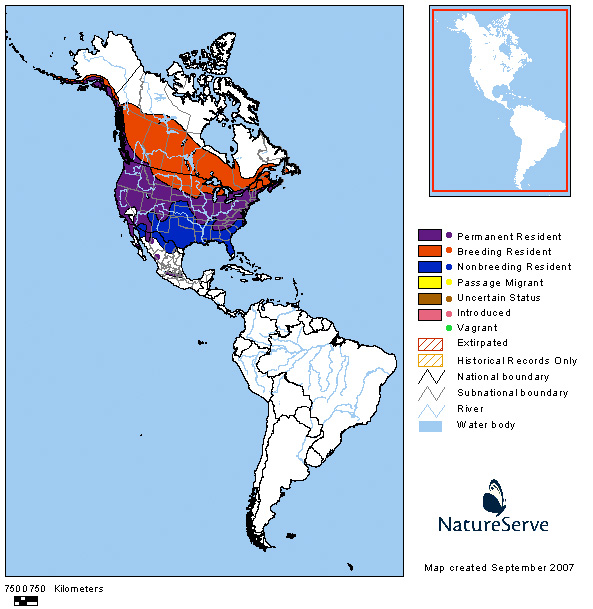

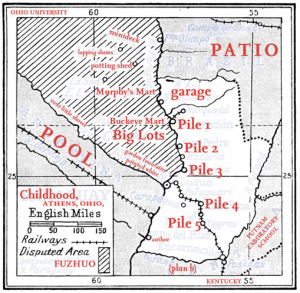

Patio is a memoir set at “30 Cable Lane, in Athens, Ohio,” a typical town that was, in the ’70s, transitioning from hemlocks to big boxes. On the one hand, the story is mythic: in Athens, Lin remembers the life and death of his father within a curated assemblage of Chinese-American and American mid-western experiences; each of the four chapters centers on some milestone event in Lin family history; related and semi-related images of ceramics, architectural blueprints, Google search results, etc., are dispersed throughout the prose; and the precise correspondence between text and image is obscure and invites projection.

The story achieves its specific focus via a bricolage of wild idiosyncrasies that Lin has scavenged from memory (or elsewhere?), retold in detail, and catalogued in the terminal index. So it is that Lin interprets the “cordoned-off Yosemite far from the streets of Athens” with a naturalist’s zeal, working to make the landscape familiar and the myth real:

I have drawn up a few maps and a timeline/list (below) to indicate some of the boundaries and rough chronological order of my father’s clay and half-clay projects. I have included the list of man-made and naturally occurring materials (they are pretty much the same) to make it easier for you to see what one childhood, in Appalachia, actually looked like at those moments when it is not reducible to anything else.

Somewhere between the “many versions” of the story and Lin’s own “childhood’s childhood” exists an old patio that was built, following Lin’s father’s vision and inspiration, of refined limestone powder. In Lin’s youth, the harvested lime, which came from natural deposits in Ohio’s Hocking River Valley, took on a new form as a construction material. It was no lifeless bag of Home Depot Sakrete, it was transcendental. Years later, through Lin’s writing, the mortar has again been mixed with water and made hard, immortalizing his father. “When I think of the patio,” Lin writes, “I think of my father’s dying, and the many minutes of it appear like items in a search string or the stones in a patio.” Reification is ancient: the Roman’s used opus caementicium to construct, among many other things, the Pantheon’s dome, which they dedicated “to every god”; in Latin, concrēt-us is derived from concrēscĕre, which means “to grow together”; a mother appears inside a computer. In short, words and their associated meanings are a lot like buildings, materials, and children. Each is a replica along a chain of iteration that points backward to its inspiration, an original idea.

Lin’s challenge is that his father, who was a pottery instructor, is now no longer living — and, when he was, he obviously wasn’t yet dead. The text suggests that this kind of circular redundancy is necessary to understanding and has three alternate titles, one of which is The Anthropology of Forgetting in Everyday Life. Hence the linguistic excavation process to re-iterate a lived life. Clay is buried underground in Ohio’s geology, but in this story it is visible everywhere, having been dug up and transformed into “1,235 pots,” which the author finds “in the house, the garage, and the yard,” and “hidden in a small room in the basement.” These banal artifacts accrue new meaning when redoubled in Lin’s “lazy chronology,” but embracing its prose is a disorienting, almost synesthetic experience that feels like stepping off a bus at 30 Cable Lane without a compass, map, or watch.

Lin’s challenge is that his father, who was a pottery instructor, is now no longer living — and, when he was, he obviously wasn’t yet dead. The text suggests that this kind of circular redundancy is necessary to understanding and has three alternate titles, one of which is The Anthropology of Forgetting in Everyday Life. Hence the linguistic excavation process to re-iterate a lived life. Clay is buried underground in Ohio’s geology, but in this story it is visible everywhere, having been dug up and transformed into “1,235 pots,” which the author finds “in the house, the garage, and the yard,” and “hidden in a small room in the basement.” These banal artifacts accrue new meaning when redoubled in Lin’s “lazy chronology,” but embracing its prose is a disorienting, almost synesthetic experience that feels like stepping off a bus at 30 Cable Lane without a compass, map, or watch.

Much the way that his father’s hands once sculpted clay spinning on a wheel, Lin’s storytelling hacks into an already circular process. Through syntactic ambiguity, he linguistically replicates the iterative function itself: “In regard to tokens the good thing about a box of chocolates on Valentine’s Day is that the box says something you do not have to, and the good thing about a token is that buses take them. The bad thing is that a token can be wrong.” With each successive encounter, the meaning of the word ‘token’ contorts. Token-ness is at once affirmed and undermined.

In wordplay, this is called antanaclasis — a single word is repeated, with a new meaning employed at each new usage — and is demonstrated in the expression, falsely attributed to Groucho Marx, “Time flies like an arrow, fruit flies like a banana.” Lin goes on to interrogate the archetypal idea behind the trope. That is, not the meaning of the word ‘flies,’ but process of transmutation between one ‘flies’ and another ‘flies.’ He asks, “What is the difference between a patio and the memory of a human being?” The author, like the reader, can and does conflate patio and Dad such that the meanings soften, evolve, and then harden. The reconstituted words are not mere analogies. The versions are biological homologs, ancestrally related. Each new version offers a new possibility for a new relationship. Mortar is an iteration of mortar is an iteration of Father, and a replica is always a thing it is not.

It follows that my dead book review has this new incarnation, “In the same way,” as Lin writes, “that Marcel Duchamp once took a used bicycle wheel and made it into something that it wasn’t but in fact was.” Further, this review, like Lin’s father’s life, will again be replicated and reproduced in smaller versions, first in logic boards, then onscreen in computer pixels, and, finally, in the loops of neurological electro-chemistry.

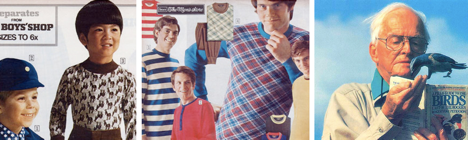

The Patio and the Index has another alternate title, A Field Guide to a Family, and I think it makes sense to read the text as a guidebook. This is appropriate because guidebooks are impressionistic, and a family on a page is not an actual family. A few years ago, I left my own family and home in western New York to study ornithology in northern Ohio, three hours north of Athens. Once there, I noticed that I could no longer recognize the common summertime tune of a song sparrow. This, I soon read, was because sparrow populations often develop regional dialects such that over time isolated communities will begin to sound dissimilar. The Roger Tory Peterson guidebook’s description for song sparrows, like any guide’s, is skeletal: “Song, a variable series of notes, some musical, some buzzy; usually starts with 3 or 4 clear repetitious notes, sweet sweet sweet, etc.” Though this sort of mnemonic sameness in nature is ridiculous, it is none-the-less easy to assume individual birds to be identical, each broadcasting a copied tape that has been passed out through a kind of genetic-code distribution system.

Historically, the epistemological trade-off between reality and representation has been a matter of life or death with regard to ornithology. Prior to 1934, when Peterson published Guide to the Birds, naturalists were trained to shoot and kill, the problematic irony of this practice being that a dead bird does not entirely replicate a real bird, least of all its song. Peterson’s identification system, for which he was canonized “father” of modern guidebooks, saved countless bird-lives, and his mental fidelity for bird song may still be unparalleled. “I can recognize the calls of practically every bird in North America,” he famously declared.

But it is worth noting that the great ornithologist and naturalist also confessed, “There are some in Africa I don’t know, though” (my italics). Peterson’s encyclopedic, super-human, super-avian mastery of avian vocalization subtleties seems to contradict reality, in which literally every bird sounds different. What then, beyond mental replication, does it mean to know a song, or a bird, or another person, or a family?

One answer comes in a variable series of musical notes. If we can find birds on the pages of books, and gods within concrete, it does not seem fantastic to encounter our parents inside of their pots and patios. Lin’s father was reminded of the Ohio countryside by “off-brand shampoos,” and “potato chips in cardboard tubes,” so it is fitting that the author remembers him inside these very things. Just as fitting as remembering him in “a music section” where Lin purchased his “first store-bought record album, Beatle Mania!,” advertised as “a collection of hits recorded by the Liverpools.” After all, a human is very much like a song sparrow, and a story like a song — or a Beatles’ album, or even a Beatles’ compilation. Every re-recording is at once a reconstructed version and something entirely new. As Lin sculpts a “sampled novel” of his father’s life and death, he also re-combines, re-enlivens, and re-connects. The circuit may not have been broken, but it is repaired.

Peter Nowogrodzki is a writer living in western New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.