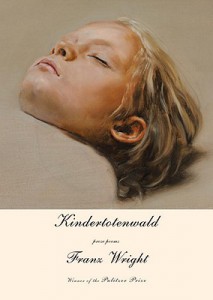

[Knopf; 2011]

Franz Wright’s new volume of prose poetry, Kindertotenwald, translates the Pulitzer prize-winner’s sensitivity for emotional distress and existential longing from verse into prose. Since it’s a Franz Wright book, it comes as no surprise that Kindertotenwald discovers and traverses new emotional spaces, new ways of naming desire, loneliness, guilt, and grief—from a poet with a long track-record of piercing, lucid insight into the human condition. We could hardly expect otherwise. Unfortunately, the relationship Wright establishes with the prose format feels less cogent—the collection contains poems that seem to “fit” beautifully in prose, but also others that seem to wander through it absent-mindedly. Kindertotenwald certainly constitutes a masterful expansion of Wright’s technical resources, it will certainly consolidate his already well-established renown as a discoverer of new affective resonances.

While it seems clear that Kindertotenwald successfully extends Wright’s track record of generating stark, sensitive revelations about our connections to others and to ourselves, it is less clear how well his sensitivity fares when transposed into the diffusive expansiveness of prose. In many poems, Wright deftly finds ways to channel his considerable powers through the freedoms (and constraints) of the prose medium, but at times, one can sense a certain discomfort in coming to terms with the realities of the format. In all fairness, prose poetry is an often enigmatic and maddening form, and while finally starting to make its way into the work of mainstream poets like Wright, it remains largely uncodified and underexplored. Furthermore, perhaps a certain difficulty inheres in the very structure of a form which, as its name manifests, is founded on a heterology: how can the delicate quality of verse, which poets have always insisted can be attributed very specifically to its formal qualities, be transposed to prose, a form seemingly designed to obscure its own status as form?

The texts I would identify as the masterpieces of the genre (including John Ashbery’s Three Poems and Vermont Notebook, Ron Silliman’s Ketjak, and Bob Perelman’s “An Autobiography”) all find ingenious and productive ways of integrating prosaic and poetic modes, whether by crafting essayistic narratives that are easy to follow at any single point but somehow never quite cohere in the way good prose is supposed to (a la Ashbery), embedding constellations of prosaic statements within intricate sculptural arrangements (a la Silliman), or distorting a preexistent prose form with unaccountably manneristic, dreamlike elements (a la Perelman).

Often, Wright is able to take advantage the unruliness of the prose format by harnessing its essential relentlessness, creating texts that slowly build to a roiling climax. “Litany”, for example, suspends a wide variety of material within a simple, driving repetitive structure, seeming increasingly to push at the constraints it has established for itself, only to close with a terse, paranoiac collapse back into form: “While we slept, no one held a gun to my head. While we slept, I hate my only friend.”

At other times, however, the fit between form and content is less comfortable, rendering the rhythm a bit choppy and the development a bit digressive. Perhaps the least successful pieces in the collection are those in which Wright’s biting sense of humor, by turns bitter and incredulous, jumps the rails and skids into a carnivalesque snarky-ness (think Ashbery without the technical precision and restraint) not necessarily becoming in a poet whose strength is spare lyricism (in “The Peyote Journal Breaks Off”: “So things do not appear to be headed in an especially auspicious direction [. . .] I switch on the TV with the idea of checking out the action on CNN. It’s not long before I discover that it is possible to weep from sheer astonishment and rage, I never knew that.”).

Often, though, we get the directed energy and sensitive control of imagistic palette that characterizes all of Wright’s best work, most notably in the lovely “Bees of Eleusis”: “The ingredients gathered, a few small red tufts of the dream spoor per sheaf of Demeter’s blonde wheat, reaped in mourning, in silence, ground up with the pollen and mixed into white wine and honey. These stored forms of light taken under the ground.”

The work in Kindertotenwald draws on a variety of sources, including literary biography and musical ekphrasis (with shout-outs to Basho, Nietzsche, Rimbaud, Saints Teresa and Bernadette, Kierkegaard, and Messiaen), history and politics (most notably in “One Hundred and First Reason to Stay into Your Room”, an odd but tidy little poem that modulates from a personal anecdote to a reflection on colonial history), and biblical and mythological material (the aforementioned “Bees of Eleusis”). The primary impetus for the collection, however, seems to be—obliquely or otherwise—autobiographical. Wright is at his best when meditating on work, youth, aging and family life.

Most particularly, Wright is endlessly captivated by the dynamics of the dysfunctional family, specifically his dysfunctional family: check out “Circle” and “The Last” for evocative portraits of, respectfully, Wright’s mother and his father (the equally prominent poet James Wright). The latter, while it lacks the effortless technical facility that Wright’s work can show at times, is gut-wrenching, brutally honest, and probably the highlight of the collection. The volume’s centerpiece—and the poem from which it draws its (gloomy) title—“The Scar’s Birthday Party” doesn’t seem to be about Wright’s own life, but is nevertheless wonderfully precise and humane in describing the suffocating family to which a successful young professional returns home: “For the time being, she is still sitting here, right next to Mother the fixed smiling glare and her husband the mumbled joke nobody gets, they appear to be sleeping, reclined in their chairs, all year long they’ve been sleeping, sleeping as snow fell, blowing all around the house, spring branches tapping at windows, each alone in their rooms [. . .]”

All reservations aside, Franz Wright fans who pick up Kindertotenwald are likely to find what they are looking for, and readers new to the poet’s work, though encouraged to check out earlier, masterful collections such as Walking to Martha’s Vineyard and Wheeling Motel, may also find much to hold their interest. More personally, I feel obligated to salute a truly mainstream poet for unconditionally embracing a difficult, inscrutable format which has long been primarily the domain of folks operating in the small-press world. Here’s hoping that Wright is not finished exploring the possibilities of the form. More specifically, here’s hoping that he continues to deploy his tremendous gifts as an affective autobiographer within the domain of the prose poem, a domain whose latent productivity lies in its inextricable fusion of truth and fiction, storytelling and poesis, life and beauty.

This post may contain affiliate links.