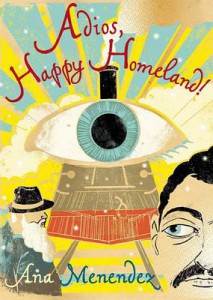

[Grove Press; 2011]

There’s a certain air of weepy nostalgia that pervades the work of some Cuban (once-Cuban, exiled Cuban, and Cuban American in particular) writers writing in English. The Cuba of their memories, or often their parents’ memories, is an elysian island, pre-Communist and therefore pre-poverty, pre-hardship, pre-exploitation—an imagined setting overripe with the untainted sweetness of the place of origin always longed for and always denied.

That’s certainly what I expected from Ana Menéndez’s latest book, and it’s partially what I got. Adios, Happy Homeland! is a conceptually ambitious project: it’s a fictional anthology of Cuban writers’ works, compiled by the fictional Herberto Quain. Readers of Borges may recognize Herbert Quain, subject of the short story “An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain,” which takes the form of an obituary. (The adaptation of “Herbert” is charming—it reminds me of hearing Karl Marx always referred to as Carlos Marx.) Adios, Happy Homeland! begins with a prologue by Quain that frames the tone and themes of Menéndez’s project:

But I know something of imagination, having sheltered under its enormous shadow-wings. And, though I may not be Cuban, I have learned to speak the language of escape. Untether your expectations; be lifted by these unseen poets struggling to translate that which has no translation. And remember what a great friend once told me: just because it never happened doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

The stories in Adios, Happy Homeland! are organized around the themes of escape and more concretely, flight. The book is presented as a collection of stories by Cuban authors and poets (some of them based on real Cuban authors and poets) and meant to form a thematic whole. They often function intertextually—a minor character in one story is the narrator of another; one story is a memory of a character in another story; etc. These connections, and the overarching idea that everyone dreams of escape, give the book a kind of welcoming completeness, a sense of a world that is comfortably held together.

But Menéndez’s greatest weakness comes from that devotion to continuity. Her narrators lean toward an overly sentimental, lyrical style. Many of the stories share a sometimes-cloying tone (this is how we talk about Cuba). They also share a common organization around a device or catch. It’s the kind of structure that discourages deep engagement with a story—understanding the story is presented as a single moment of realization that has to be reached. In a way, the use of Herbert Quain is an instance of this kind of trick, and one that is slightly puzzling. It’s cute, yes. But why a character from an Argentinean writer for a book purporting to have something to do with the Cuban literary imagination (other than that Borges is the most recognizable Latin American writer outside of Latin America, and the Ficciones his most recognizable collection)? Why not, say, more of a reference to Alejo Carpentier, for example, an extremely complex (Cuban) writer whose frenetic, surrealist style has much more to do with Cuban literary consciousness? Or something from José Martí, revered as the father of Cuban independence? It is a question of audience, to a certain degree, and accessibility, but it’s also a sacrifice of meaning for neatness, for schtick. It is also worth looking at the impulse I’m indulging in here, to politicize works by Cuban authors, to necessarily read them in the context of nationality. And yet Menéndez’s work trades heavily in nostalgia and in the sense of longing for the Cuban homeland; it would be a stretch not to read this book in terms of Cuban identity.

The use of a device works better in some instances than others. Some of the stories are truly provoking. In “End-less Stories,” a choose-your-own-adventure loop of infinite regress, the brevity and restraint of the story work to powerful effect. Menéndez is at her best in some of these more experimental, less narrative pieces, particularly those that explore language and translation. There’s more to play with here. “Zodiac of Loss” is one of the cleverer pieces. The narrator speaks to each sign of their qualities, and their coping with loss (the loss, on the surface, is alphabetic—there’s no letter “e” in this story). One of the best is “Un Cuento Extraño,” the only story in Spanish, a dialogue between two characters who wonder why they are speaking in Spanish when they’re from New Jersey, and whose jokes are made in the awkward linguistic occurences that sprout in the spaces between English and Spanish. The titular story, “Adios Happy Homeland: Selected Translations According to Google,” is a clever and at times hilarious selection of e-translated classic Cuban poetry. Lines from José Martí’s famous Versos Sencillos, a kind of anthem for Cuban nationalism, become jarring fragments of lost and misplaced sentiment:

Callo, and understand,

and I take the pomp of rhyming;

hang a withered tree in my hood doctor.

Well, if that doesn’t speak for itself. And Menéndez lets it.

This post may contain affiliate links.