I just finished reading Alfred Kazin’s book Writing Was Everything, written 1995 and worked up from his Massey Lectures at Harvard. It’s a zeitgeist tour through the literary landscape of New York City and wartime Europe from the Depression to the present, told primarily through readings of and anecdotes about writers – Albert Camus, George Orwell, Richard Wright, Edmund Wilson, Czeslaw Milosz. The vitality of Kazin’s writing is so moving, so infectious, and his portraits of the writers and intellectuals of the day so enticing and intimate, I wanted to share some here.

I just finished reading Alfred Kazin’s book Writing Was Everything, written 1995 and worked up from his Massey Lectures at Harvard. It’s a zeitgeist tour through the literary landscape of New York City and wartime Europe from the Depression to the present, told primarily through readings of and anecdotes about writers – Albert Camus, George Orwell, Richard Wright, Edmund Wilson, Czeslaw Milosz. The vitality of Kazin’s writing is so moving, so infectious, and his portraits of the writers and intellectuals of the day so enticing and intimate, I wanted to share some here.

This is Kazin on Richard Wright:

I knew Wright a little, occasionally had dinner with him at Frank’s Restaurant in Harlem. He was handsome, restlessly eager, and, even when Native Son in 1940 astonishingly became a bestseller, unsatisfiable. Like many writers of the thirties who had grown up in the deepest poverty, Wright looked professionally angry. …Not for the likes of them was Edmund Wilson’s praise of Hemingway for showing “grace under pressure”; that was in another country. Wright’s country was Mississippi in the twenties, when he was stripped naked by his mother and badly beaten with a barrel stavebecause he had fought back against somewhite boys. He was slapped aorund by his grandmother, a fanatical Seventh Day Adventist, for repeating a story she called “Devil stuff in my house.” After he retaliated with a cuss word, she beat him so hard that he was sure she would kill him ifhe didn’t get out of her reach.

“I used to mull over the strange absence of real kindness in Negroes,” Wright wrote in Black Boy, his extraordinary personal history of unrelieved oppression both in and out of he black community. This book becomes a distinctive literary accomplishment through Wright’s most striking technical gift: his sense of momentum, his way of seeing life as act after act in an atmosphere of undeviating cruelty. The reader gets breathless sharing Wright’s intensity.

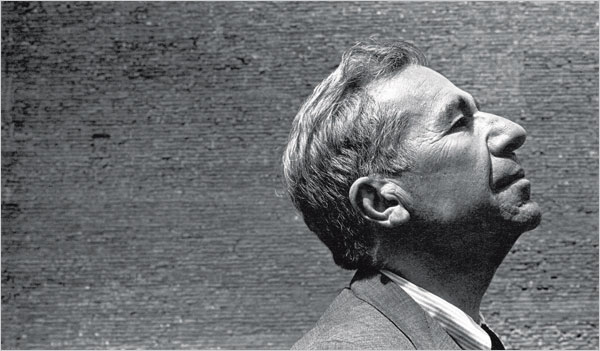

Here is the soulful Abstract Expressionist painter Mark Rothko:

I never knew why Rothko, grown rich and world-famous, was so unhappy, or why he talked as a matter of course from the bottom of his soul while standing, a desperate millionare, apart from the noisy party in his own house. But the mystery of his unhappiness was like the musrty within and around those large rectanges, swimming in interior spaces, increasingly dimmed (as Rothko neared his end) by muted colors and black borders. …Rothko’s longing for intimacy haunted me, as did his round, spectacled face knotted in pain behind all those plain-spoken admissions about the loneliness he felt in the world. He was looking for something beyond the merely personal (which in our time means psychological), and I, without knowing anything much about him, dared to call “some reason for our existence in this world.” Some reason not just for his own existence, nerve-driven as that was for him, but perhaps for the existence of the world itself.

The absolutism of Flannery O’Connor and Saul Bellow:

The self-assured Bellow did not like to admit that there were other writers. When Hannah Arendt joined his Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago, and of course lectured him as she did the rest of us, he was outraged by such presumption and dismissed her in Herzog as “canned Weimar sauerkraut.” The reclusive, deeply ailing O’Connor–she did at thirty-nine of lupus–recoiled from any view different from what was for her the central incarnate truth of the Host. Fellow southerners like Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams made her sick; literary folk from the ghastly northeast she caricatured as “interleckchuals” in her novel Wise Blood. She was so inflexible in her standards that her own parish priest, driving me up to see her after I had spoken at a nearby college in Georgia, remained in the car ring my brief, tight visit, saying that her disapproval of his usual light reading matter made him afraid to see her out of church.

And, in the last pages, here is the poet Czeslaw Milosz:

Milosz is important not because he lectures us on the European agony we did not experience, but because of the example he sets as poet and teacher. Poetry to him is profoundly a recall, not a mere presentation of lived experience. It resembles what he calls “the cries of Job,” not our endless defense and explorations of the ego. Everything depends on what is left of faith after credulity has vanished from our practical, issue-tormented lives. It is important, essential, to restore the fundamental recognition that the world remains as strange to us as it ever was.

This post may contain affiliate links.