Jeff Martin and

The Millions‘ C. Max Magee (Soft Skull Press, 2011), and our panel consists of five Full Stop editors – Alex Shephard, Amanda Shubert, Eric Jett, Max Rivlin-Nadler, and Jesse Montgomery. Our discussion happened (continues to happen) over a long e-mail thread in which we responded to the book and to each other, so the pieces we printed below are not essays so much as shares in an ongoing conversation that will extend from Monday to Friday, with two or three voices represented each day. Check back for daily updates.

* * *

Alex Shephard (Full Stop Editor-in-Chief):

x

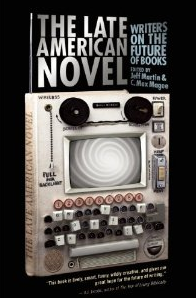

There’s only one thing that the writers featured in

The Late American Novel: Writers on the Future of Books agree on: making detailed predictions (prophecies?) about the future is a damn good way to make a fool of one’s self. Pick up a newspaper (just out of curiosity, when was the last time any of you did this? I think I recall buying — and reading! — the Sunday

Times sometime last summer, but I may just be imagining things) or, more likely, go to a newspaper’s website tand the top stories — Japan, Libya, Charlie Sheen — are all things that none of us would have seen coming in early January (well, Charlie Sheen maybe, but uuuuuuuggggghhhhhhh).

Despite the fact that the subject of this collection — the future of the book — is something we, the writing community, like to yak to each other about, it’s a remarkably difficult subject to write intelligently about for a pretty simple reason: if you’re asked to write about the future of anything, the first intelligent thought you will probably have is that 1) you have no fucking idea what the future is going to be like and therefore 2) if you make bold predictions (or even maybe incisive ones) you will probably be wrong (unless you are William Gibson).

This anxiety about prophecy is one not-so-hidden current fidgeting its way through the vast majority of the essays in The Late American Novel. The essays I found least compelling were those that either attempted to ignore (or transcend) this anxiety, or those that seemed burdened by the real or imagined expectation that they had to predict the book’s resurgence or failure or to provide a course for it through the murky, uncertain waters of the present into a more stable future. Generally, the essays that buckled under the pressure of prediction were the most disappointing — I’ll pick on John Brandon (whose work I admire, by the way), whose “The Three-Day Weekend Plan” is emblematic of the few essays that fall under this category. It starts off with a great deal of promise: the struggle of making a living writing, talk of the “rebellion” that often propels American letters into interesting, uncharted territory. But by the final third, there’s pressure to conclude and Brandon starts going on about how maybe the novella is the key to the future, and I am left scratching my head — an interesting essay about, among other things, mass culture’s influence over literary culture, collapses into vague idealism.

x

On the other hand are the essays that attempt to transcend anxieties about the future, which tended to be the most abstract — more Borgesian (sadly more often faux-Borgesian) fables. For example, here’s a passage from Lauren Groff’s “Modes of Imagining the Writer of the Future”: “If the writers of the future all look just like James Patterson…it is because they all are, as a matter of fact, genetically cloned replicas of James Patterson.” Groff’s essay is a fun read, but I felt it gave me more insight into Lauren Groff than the future of print: the writer of the future is Groff in the present, though I guess maybe that’s the point.

But this is an unfortunate way to start a discussion on a book I actually liked, a book that I found to be endlessly fascinating and enjoyable. Of course, many of my favorite works of non-fiction are those that are filled with arguments I disagree with — I still read Chris Hitchens for this reason. I’ll send some redemption Groff’s way by quoting from her (sensitive about put-downs myself, I hate dishing them out, though I am working on toughening up). “A writer of the future knows that no matter where she sets her work (in the historical-fiction past; in the science-fiction future), all she really is doing is talking about the present.” This is an idea that any reader of science fiction will recognize. In fact, the best science fiction is not just about the present, but about the strange, quantum energies that are altering it, as well as the values, ideas, and institutions that keep it tenuously tethered to the past. I would argue that the same is true in The Late American Novel — my favorite essays in the collection are those that shrug their shoulders at what others saw as the task at hand — predicting the future — and instead get at something subtler and more insightful. Some of these essays present conflicted feelings about the rise of connectivity and emergence of electronic literature, or, perhaps, the writer’s insecure place in the future. Others interrogate the past as a means of locating not only where we stand in the present, but which direction we’re facing. Many do a number of these things.

x

The most compelling pieces were authored by

n+1 founders/new faces of public intellectualism Benjamin Kunkel and Marco Roth. Kunkel’s “

Goodbye to the Graphosphere” and Roth’s “

The Outskirts of Progress” are provocative, insightful and sharp as knives. Unsurpringly, they both rely on the particular Marxist-ish approach that defines much of the work in n+1. While the majority of contributors to

Late American see the novel’s future from a deeply felt, personal position, Kunkel and Roth take on a historical perspective. Both build on the not particularly controversial notion that the dominant medium of cultural exchange alters the culture in question and, consequently, the role of literacy and art in said culture.Just as the rise of newspapers altered the 19th century novel and the rise of television the 20th, they argue, the rise of digital culture will not only alter the novel — “people will write to the screen, as they do already,” Roth writes, “shorter sentences, quick blocky paragraphs, desperate bids to grab the reader’s flickering attention” — but could diminish its position as well. Roth believes that there is a deeper crisis at hand: “our free will to culture,” that a culture first must be devoted to “thought, inquiry, and rhetorical expression.” Kunkel argues that the culture of literature is losing ground to the culture of commentary, that books will persist, but that literary culture is “waning.”

x

I’ve highlighted Kunkel and Roth’s contributions because I think that they provide an excellent introduction to the other anxiety that hovers over

The Late American Novel: that the book is at least changing — becoming digitized — or at most declining. There is a formal element to this change — e-books and the internet — but Kunkel and Roth both suggest that what is perhaps more interesting (and more troubling) is that these new media coincide with vast

cultural changes: to put it simply we are not only processing information differently, but relating to one another differently as well. Thus, writers are faced with three major changes: formal (digital lit), economic (the supposed decline of the industry), and cultural (see previous sentence). To briefly touch on another essay I admired — Jonathan Lethem and David Gates’ correspondence piece — perhaps the biggest reason I haven’t found fictional representations of social networking to be particularly compelling (

Super Sad True Love Story and

Tao Lin aside) is that writers have approached this as a primarily formal change, without fully grasping the cultural changes your Facebooks and Twitters and DrudgeReports have wrought. Unlike other media (film, but especially visual art), the novel has been remarkably resistant to the avant-garde. To paraphrase Zadie Smith, the social novel remains the dominant form. And, as Lethem writes, the novel is “the most post-modernism-resistant art form.” I wonder if a truly digital book — an e-book written (developed?) to use the medium’s incredible potential, not just its data storage — could be for literature what the Duchamp’s urinal was for visual art.

One final note in the “what I liked” vein. I’m rather dispirited that my favorite essays in the collection were written by people whose work I already know and admire (Kunkel and Roth, Lethem and Gates, Victor Lavalle, Emily St. John Mandel, Rivka Galchen) and only really liked two pieces two writers whose work I was unfamiliar with — Reif Larsen and Kyle Beachy.

So that was much longer than I wanted it to be! Thanks for bearing with me.

Still living in the graphosphere,

Alex

* * *

Amanda Shubert (Full Stop Features Editor):

I should begin by saying that I see little evidence that the novel is dead or dying. In spite of competitive information technologies and the new (though no longer that new) time-wasting demands of the Internet, it is not at all clear to me that people are no longer reading or no longer reading books with pages and covers. In fact, as Jesse pointed out in his blog post here, more books were sold in 2010 than almost any other year in the past two decades. But this brings me to another point, one Alex referred to in his comments: when we talk about the future of the book, are we referring to an economic reality, or a cultural one? Do we mean the future of books-as-objects or the future of reading? And when it comes to reading, do we mean reading novels, or reading anything at all? The editors of The Late American Novel don’t offer much clarity or direction; and their overarching questions—“Will books survive? And in what form? Can you really say you’re reading a book without holding on in your hands?”—just don’t strike me as terribly productive ones.

My favorite piece in the collection, an e-epistolary between writers David Gates and Jonathan Lethem originally published in Pen America’s “Correspondences” issue, is also the funniest and most self-deprecating about the impulse to eulogize the book; it begins: “Hey, David. As I was saying to be 2,472 friends the other day, these certainly are strange times in the history of the boundary between the human persons and the written words.” What follows is a conversation between two old pros talking about what they know, teaching and craft, with the nimble banter of writers who can’t help but come alive in words. It’s wry, clever and eminently likeable; it makes no grand claims; and it assumes, as Alex referenced earlier, that in spite of cultural and economic upheaval novels manage to retain a basic function and shape. Lethem writes:

I mean, I’m no David Shields, but I’ve made my own passing gestures at appropriation, and yet fiction—the old transaction, the old transmission—just seems to springily retake the basic shape that it was put into by Austen and Dickens (a shape only mildly deformed, in the end, by your Becketts and Barthelmes), time and time again.

Lethem and Gates’ essay reminds us that the job of writers and critics is to practice their craft, to do it as gracefully and honestly as possible, in times that are difficult and often inscrutable and the future portentous and bleak. But not more portentous and bleak than the future has always seemed for writers sensitive to crisis and schism their work cannot help but absorb, writers who lived in times as ordinary and extraordinary as ours, and often under threat of much more imminent danger – Virginia Woolf and T.S. Eliot writing in the wake of the first world war, or, for a more recent example, the 1960s counterculture movement as mythologized by Joan Didion, whose work embodied the modernist aphorism that things fall apart. To claim otherwise – that the invention of the Internet and the Kindle makes us all of a sudden vulnerable to cultural disintegration – is naïve and insulting.

Editors Magee and Martin don’t quite exhibit that level of hubris, and yet the book does, by omission and by failing to contextualize the issues it claims to examine. And in so doing it mishandles its subject – books as objects and their significance to us, the novel as a cultural form. (Benjamin Kunkel begins to begin to address the historical dimension of these issues in a helpful way in “Goodbye to the Graphosphere.”)

For all these reasons, I was also sympathetic to Victoria Patterson’s essay titled “Why Bother,” which suggests (accurately) something of its content. Patterson writes, “I brood over my work rather than the fate of the book industry.” Right.

-Amanda

The Full Stop Book Club is a regular feature in which Full Stop editors and guest contributors discuss a book in detail over the course of a week. Our first Book Club selection is The Late American Novel: Writers on the Future of Books, edited by

The Full Stop Book Club is a regular feature in which Full Stop editors and guest contributors discuss a book in detail over the course of a week. Our first Book Club selection is The Late American Novel: Writers on the Future of Books, edited by