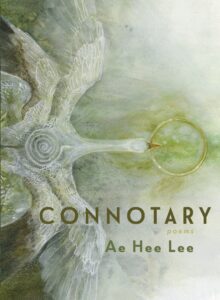

[Bull City Press; 2021]

Ae Hee Lee’s Connotary is a chapbook of seventeen stunning poems, selected by Tiana Clark as the winner of the 2021 Frost Place Chapbook Competition. This compact collection contains a multitude of nuanced reflections on transitory spaces, liminality and migration, and the blurring of boundaries between the body, the memories it contains, and the earth. Through her precisely beautiful lyric, Ae Hee Lee offers vivid remembrances of family, gesture, and place; she examines pasts and origins; she imagines new futures.

Lee’s poems are serious and calculated without ever losing the honest grace of what it is to be human. For those of us who consider ourselves migrants, or who grew up as children of migrants, between spaces and cultural codes, the poems of Connotary capture scenes that are familiar: time spent waiting, walking, in airports, in kitchens. Travel is not merely a passive act, it is a routine examination of one’s belonging, of what the body brings from one place or family to the next.

Connotary bends time and space, both in the literal sense of traveling between disparate geographies, but also through a rich relationship with memory. Memories are presented both as holy and matter-of-fact. In the opening poem, HYU : : IN-BETWEEN, the narrator recalls her and her sister waiting on the train’s platform with their mother as they would “practice the art of climbing stairs / slowly, anoint each step with the shadows of scissors, wolves, / shapeshifters we call hands. It’s a quiet / and passionate affair—to dwell / in the meanwhile.” Part of being between spaces is also having a very intimate relationship with patience and slowness. Waiting becomes cultural. It is in this waiting that we tend to one another, to small moments, which become the foundation of who we are and how we remember our lives years into the future. The final lines of this opening poem were ones I returned to often in my reading of the chapbook: “And a train nuzzles the station, / as it arrives, arrives, and arrives.” The train does not simply appear, now in its new space, ready. The arrival is gradual, and it is continual, so much so that it becomes a state rather than an action.

I particularly fell in love with Lee’s poem CHICAGO : : RE-ENTRY RITUALS, which cemented just how much rituals are central to the dynamics at play in this text. Migration in itself can be ritualistic, a regular crossing back-and-forth (if one is able to), and the gathering of objects. Lee writes: “I’ve become an expert / at packing exactly 50 lbs. / worth of breadcrumbs.” The spaces of transit, like airports, like the train station, are mazes which the body comes to know: “I wander through / the labyrinth of customs, / praying for safe passage / in a mixed tongue.” And in these spaces of ritual movement, we are asked to consider our function: “What’s the purpose of your visit? / they ask. What’s the purpose of me? / I ask and answer myself: / to be reunited with love, waiting / at every side of the border.” Here, the visit and the body blur — arriving to a place is arriving to a self. And upon arrival, ritual, too, is a grounding act. Rituals, like food, like memories, bring the past to the present. They conjure spaces that are not physically present; they are forms of cultural persistence. This thinking is also present in the poem NATURALIZATION : : MIGRATION: “The space / it would take up / in the immigration bag / my parents passed down / to me: dark, foldable closet / I’ve dragged / from country to country.” The ritual of travel and migration is intergenerational. It permeates across family lines, so that multiple eras feel the ripple effects of such movement.

Moving backwards for a moment — before the book even begins, the reader is confronted with an epigraph from Alberto Rios: “Words are our weakest hold on the world.” I am always appreciative of texts which are aware of their own limits, that in some way embrace the notion that the complexities of time and place are not capturable on paper, but who choose to live in this space of absence, and to see what can flourish inside of it. Rios’ epigraph brings to mind language’s failure, a failure that is inherent — there is always something missing. As I am always looking for an opportunity to quote Anne Carson, I will quote her thinking in Eros the Bittersweet, wherein she tells us that “the words we read and the words we write never tell us exactly what we mean.” The correlation between experience and language is never an exact match, yet this in-between space is still a space of creation. Love and desire, too, are never exactly as we want them to be, but still, there is beauty in that lack, in what is not present, in what is not expected. Suspended here, in this partial failure, the structure of language can still show us truth. Lee echoes this in the poem MIDWEST : : EQUINOX, where she writes: “I think I’ll never grasp the true / width of the world.” Places trick us and edges blur; there is always something unreachable. But for a body in transit, between, that is a known state, and in this state, the body continues to learn new things.

In this known state, displacement creates its own logic. In Lee’s poem KIMCHI : : IN TRUJILLO, the narrator paints several vignettes in the kitchen alongside her mother: details of smells and objects abound, alongside a recollection of the mother slicing onions into “whatever size she thinks would be ‘a pleasure to eat.’ / My mother’s measuring tool: her intuition.” The preparation of food is a vibrant site for diasporic reflections. Kitchens are quite literally places where the past often meets present: the passing of things on to future generations; old places being conjured in new ones, all through the concoction of a single dish.

And of course this condition of in-betweenness is not a neutral one. There is a grief in liminality, as I am sure many thinkers and poets have intuitied before. In TRUJILLO : : HOMECOMING, she writes: “I don’t / remember whether to turn my face left / or right. I whisper, it’s okay / es normal—for there to be sorrow / in forgetting how to cross / through gaps, now filled / with gossamer veils of time.” Even for the most well-versed of movers, the body has its limits. It is heavy to be in a constant state of flux. Lee further recalls: “When I was younger, / I orphaned many books; / now I just carry / this guilt, / a longing / for roots…” With movement, things must be left behind, and despite it being such a regular occurrence, the author here still longs for a sense of stability and stillness. Roots evade the in-between body; when multiple places are home, sometimes no place is.

Each title in the book contains two words or phrases connected by two colons. In recent years, I’ve observed or participated in more conversations about punctuation than I ever thought I would, but I actually have become especially enthusiastic about the prospect that these symbols can mean so much more than their immediate utility. I am at the stage where I’m excited about saying — Yes! The colon does, in fact, bring to mind living in duality while also orbiting a space of constant movement and connection. The colon designates a before and after, a passing on of one piece to the next, a second half or arrival that would not be possible without a first half, a departure. But the colon is also a fluid middle, a connection — and this is where Lee situates herself.

In the chapbook’s penultimate poem, BOUGAINVILLEA : : PAPELILLOS, the narrator recounts a story of walking down the street with Alejandra, a frequent companion in these works. She recalls: “We don’t stand too close; we don’t interrupt the rustle of paper chalices / above our heads. We wait, under the latticed shade, stay / still to understand what it means to sway.” Returning once more to the notion of waiting and stillness, I was fascinated by the decision to sit in the swaying, as if true stillness is not an option. This swaying brings to mind the continuous arrival of the train, the condition of arriving and going, finding beauty in the continuity, even as it slows. Observing the bougainvilleas, both the narrator and Alejandra place their bodies in relation to the earth. They sway the way the branches sway in the wind. They want to understand this sensation; they need to.

Lee concludes the book with another favorite poem of mine, in which she calls herself the daughter of a bridge. I found this to be incredibly impactful and poignant both in its simplicity and in how accurate this image is in capturing what it means to exist in / from migration. Bridges are structures that connect two places but are, in themselves, spaces of transit and transformation. The bridge is neither here nor there, but it is essential in connecting the two. It is a space on which to land and move and arrive and pass through and depart and, when on the bridge, still, you may consider yourself to be between realms.

Through Connotary, Lee helps the reader to see that this state of liminality, despite being haunted by pain and loss and abstraction, can also be — and often is — sacred.

Sarah Sophia Yanni‘s writing has appeared in DREGINALD, Feelings, Autostraddle, and others. She is the author of ternura / tenderness (Bottlecap Press) and is Assistant Editor of The Quarterless Review. A finalist for BOMB Magazine’s 2020 Poetry Contest, she lives and works in Los Angeles.

This post may contain affiliate links.