In her book The Intimacy of Four Continents, Lisa Lowe investigates the connections between the emergence of European liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic African slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The book addresses how the relationship of genocide, appropriation, and dispossession is integral to liberal thought, even though liberal thought often seeks to present itself as transcending these contexts. She argues that “freedom,” one of the cornerstones of liberal thinking, has fed on the idea that other subjects (“slaves,” “savages,” “coolies”) as well as other practices and geographies, are placed at a distance from the “human,” and shows how various narratives and strategies have justified colonial violence as part of the progress towards that “freedom.”

Towards the end of the first chapter of her book Lisa Lowe writes: “ . . . I do not move immediately toward recovery and recuperation, but rather pause to reflect on what it means to supplement forgetting with new narratives of affirmation and presence.” How can the pain of those lost and forgotten be made present now? How do we supplement forgetting?

How?

She acknowledges that it is difficult, that there is “an ethics and politics in struggling to comprehend” what has happened and how history is presenting itself to us now, but suggests that if we learn to read “across” in order to “nuance connections and interdependencies” and “engage slavery, genocide, indenture, and liberalism as a conjunction” we may discover the past and its legacies in a new light.

Towards the end of the first chapter of her book Lisa Lowe cites Stephanie Smallwood, a historian of the seventeenth-century Atlantic slave trade who has written: “I do not seek to create — out of the remnants of ledgers and ships’ logs, walls and chains — ‘the way it really was’ for the newly arrived slave waiting to be sold. I try to interpret, from the slave trader’s disinterest in the slave’s pain, those social conditions within which there was no possible political resolution to that pain. I try to imagine what could have been.”

What were the social, economic, and psychological conditions that prompted “the slave trader’s disinterest in the slave’s pain?”

What could have been?

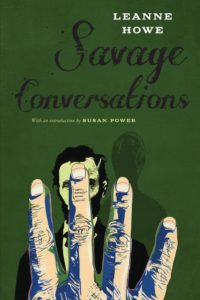

LeAnne Howe’s play Savage Conversations activates this space in history. She fills the wide-open gaps with a narrative of “what could have been,” makes the absences present in very intimate ways. It smells “fishy” in the room of where this past revisits a woman and tells her:

And you, dressed in a stinking nightshift,

The one you refuse to remove all these months,

Can never cover the past.

The woman is Mary Todd Lincoln, former wife of slain President Abraham Lincoln. The one speaking to her is Savage Indian, “One of the thirty-eight Dakota men hanged the day after Christmas, December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota,” in what has been described as the largest mass execution in United States history, attended by about 4000 white settlers. The year is 1875, thirteen years after the execution and ten years after Lincoln’s assassination. The site of where most of Savage Conversations takes place, often in the very early morning hours amongst candlelight, is a room in Bellevue Place Sanatorium, 333 S. Jefferson Street, Batavia, Illinois. Mary Todd Lincoln has been committed to this bedroom after she was brought on a trial for insanity. Her only surviving son Robert had testified against her and Dr. Willis Danforth of Illinois, who had treated Marry Todd Lincoln for “nervous derangement and fever in her head” attributes her condition in part to her belief that an Indian Spirit visits her nightly and slits her eyelids “and sews them open, always removing the wires by dawn’s first light.”

In Scene 1, “They Speak of Dreams,” that spirit grabs her by her shoulders, pulls her in and says to Mary Todd Lincoln:

Because with your eyes sewn open you still see nothing.

I read this and I realize, again, I never know what comes first, I don’t know what is the order of causalities, even though it feels as if my eyes are sewn open to see it very clearly laid out in linear timelines of progress and growth wherever my European ancestors went. Is there first peace and paradise and then invasion, then greed and blindness and injustice, then violence, then revenge, then trauma, then mourning, then revising, then repatriation, then healing, then forgiving? Or is there a different order where it all happens at once, all the time, over and over again? Could I tell, if I could close my eyes and look somewhere else?

LeAnne Howe offers many entry points to imagine what is happening and why in that room between Mary Todd Lincoln, Savage Indian, and a third character, called The Rope (“both a man and the image of a hangman’s noose” that was used during the execution of the Dakota men). The atmosphere she creates makes the trajectories tangible. There is tension. If something smells “fishy,” there will be people who go where that smell is coming from.

Savage Indian comes nightly as a man, as a vision, as a spirit, as a condition, a precondition, a legacy, a “ghoul, specter, poltergeist, banshee” and maybe as a direct reference to Noble Savage, the invented, malleable figure that helped European colonists to contextualize and justify some of the contradictions and crimes the American nation is founded on – which is to admire, glorify, cherish, respect, idealize and degrade, exploit, benight, kill, destroy and exterminate one and the same people at the same time.

Savage Indian tortures Mary Todd Lincoln physically and he arouses her sexually, he keeps her from sleeping at night. He “serves a mad woman’s unearthly pleasures.” He talks to her, he grabs her and binds her legs and arms, he quotes Shakespeare, he drinks water from her china teacup, he sleeps in her chair, he cuts out her left cheekbone out, he places her wedding ring on his little finger, he dances a waltz with her, he gently caresses her face, he cuts her eyelids, he takes her scalp and holds it up like a trophy, he chants a warrior’s call, he studies her accounts, he reads aloud from the Chicago Tribune, he shackles her to a chair fifty-seven times in one night, he reads to her from her Bible, he fills her gaping mouth with fescue and sod, he yawns and he laughs, he cuts her hanging body down from the rafters, he holds her tenderly in his arms like a lover, he forces her head up, he knocks her to the floor, he hears the Dakhóta drumbeat.

What he does reads like America. It’s very complex and very American and out of the many entangled complexities I am curious about the connection between revenge and pleasure, being revenged and being pleasured by that revenge. “You desire agony, Gar Woman,” says Savage Indian and it makes me wonder: What kind of satisfaction comes with the action of inflicting hurt or harm on someone for a wrong suffered at their hands, and what kind of pleasure comes with receiving such vengeance? Who has the need, the right, the duty, the perversity? How is emotional pain yoked with delight, or relieved through violence? Why is there a proverb that says: “Revenge is sweet.” Why does Mary Todd Lincoln coo with pleasure when Savage Indian binds her legs and arms?

Why does she say: “Such pageantry I’ve missed since Mr. Lincoln’s demise.”

What is revenge?

Savage Indian says:

When I am myself as I am tonight, every word is weapon.

When I am myself as I am tonight, why can’t I forget what happened and

Take you amid the dried-up tingling in my head,

The dried up prickle between my legs,

The ravaged filaments of desire.

Malcolm in William Shakespeare Macbeth puts it this way:

Be this the whetstone of your sword. Let grief

Convert to anger; blunt not the heart, enrage it.

Revenge. An instinct? A tool for survival? Cathartic? What if one only has the whetstone but no sword, because one doesn’t carry weapons? Whom or what do you whet with that stone? And how?

Are those questions even relevant to ask if I don’t specify if the revenge I am talking about is being performed in literature in the form of words, acted out in sports in form of games, put into action in war in the form of retaliation, triggered in the nervous system in the form of rage circuits, studied in science in the form of a series of experiments on rats or college students, institutionalized in politics in the form of laws, perverted on the Internet in the form of revenge porn, in the heavens in the form of divine judgment, in education as a series of deterrence strategies?

The revenge in LeAnne Howe’s Savage Conversations may be situated in the realm of rewriting history. Literature. She uses words that describe hate, brutality, tenderness, compassion, rage, calculation, rationality, absurdity, and logic in the interactions between Savage Indian, who when he was “a human being, would sing the air thick with Dakhóta songs” and this white woman, who was a jealous wife, and possibly an abusive mother with Munchhausen syndrome, and a former First Lady with post traumatic stress disorder, and possibly an abolitionist but maybe not, and possibly a traitor, and possibly insane, but also a daughter, and a widow, and a little girl, and a historic figure, and a celebrity. In an asylum called Bellevue she asks for it. Or did it come on its own terms? Why are Meursault’s last words in The Stranger by Albert Camus:

For everything to be consummated, for me to feel less alone, I had only to wish that there be a large crowd of spectators the day of my execution and that they greet me with cries of hate.

And why does “Savage Indian” deliver? Why does he come, night after night? Isn’t that a lot of work? Is it his duty to “Fire!” and emancipate, is it a pleasure to call her “Liar,” and tie her up, is it a means of surviving to account for the Millions of Natives dead and still be able to say: “We live. We live. We live. We live.” Is it a necessity, is it an honor, is it a responsibility, a way to mourn, a relief, an opportunity to add blank pages and let the reader imagine “Artwork of two hangman’s nooses.”

Whatever it is, it’s very effective. The images stick. The questions linger: What were the social, economic, and psychological conditions that prompted “the slave trader’s disinterest in the slave’s pain?”

For a few months I made it my routine to visit the American Wing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC once a week, and the more often I went the more sick I became of going there and the more addicted I got of having entangled myself in the “contradictions on which this nation is founded,” trying to figure out how one could get out of such entanglement. Michael Gross writes in his book Rogues’ Gallery: “The Metropolitan is more than a mere drug, though. It is a huge alchemical experiment, turning the worst of man’s attributes — extravagance, lust, gluttony, acquisitiveness, envy, avarice, greed, egotism, and pride — into the very best, transmuting deadly sins into priceless treasure.”

One of the first sculptures that started me getting addicted to getting sick in the Met was “Indian Girl, or The Dawn of Christianity,” carved in 1855-56 by Erastus Dow Palmer, six years before the 38 Dakota men were hanged for their actions in the Dakota War against White Settlers. “Indian Girl” is a full length, semi-nude female figure in white marble, and the neoclassical sculpture caught my attention first, because it looked like a naked teenage girl looking at her cell-phone. Yet it wasn’t a smart-phone she cradled in her elevated right hand, it was a crucifix, which the young “Indian Maiden wandering listlessly in her native forest gathering bird-plumes” had found and picked up and “which impressive emblem she, seeing for the first time, gazes upon with wonder and compassion,” as Erastus Dow Palmer introduced his symbolic program of the statue to Hamilton Fish, his patron. Whoever wrote the label at the Met added: “Her left hand, holding the forgotten feathers, rests limply at her side.”

Depending on the direction with which one wanders through the rooms of the American Wing at the Met, one comes upon a second sculpture, the “White Captive,” carved 1858-59 by the same artist, three years before the 38 Dakota men were hanged for their actions in the Dakota War against white settlers. This time, the label says, the nude “portrays a young woman who has been abducted in her sleep (her nightgown hangs from the tree trunk) and held captive by American Indians. Bound at the wrists, she clenches her left fist behind her back in defiance. Palmer was commended for his choice of a “‘thoroughly American’ subject, which consciously alluded to ongoing frontier skirmishes between Indians and white pioneers.”

From the very first time I looked at those sculptures and read the labels I felt deep disgust and rage at the men who made, looked at, paid for, praised, and exhibited them. And yet I also felt pleasure walking around them, looking at the details, which made me feel stupid, which then enraged me again. Nevertheless, even though deeply perverted, on some strange level they are beautiful.

When at midnight Mary Todd Lincoln says to Abraham Lincoln: “My bed, always a catafalque to you” as if he is in her bedroom, I thought of the “White Captive” standing naked in this big morgue we call a museum. And when Mary Todd Lincoln says: “Here, at last, I’ll tell it all: I did wish you dead, sir, eight thousand thirty-nine times for all the days you ran sideways from our home . . . ” I wondered if she not only wished him dead because she was still jealous that he may have loved this other woman Matilda, “who captured his imagination,” or if she may also have wished him dead for eight thousand thirty-nine other reasons.

It most likely will take a long time to confront, untangle, and rewrite the past. In an New York Times article “Can Museums Heal History’s Wounds” Chip Colwell writes: “By my estimate, in the United States alone, it will take more than 200 years to consult with descendants on all of the Native American human remains in museums.” This activity, he argues “can turn museums from places of colonialism into mediating spaces that confront and then move beyond their own pasts,” beginning by re-filling the galleries that will be pretty empty once museums have returned the treasures that have been stolen and looted from colonized lands.

There are six pages in Leanne Howe’s play that contain nothing but a single line in cursive font. They all describe an artwork.

Is it time to put “The Indian Girl” and “The White Captive” into the storage unit and make room for some new works? What about it? Would Savage Indian say:

When I look at your world, I weep

Because in the end, even your life is a captivity account.

Maybe we are all captives of one sort or the other.

Franziska Lamprecht is an artist who started writing as an extension of the long-term process based works, she produces together with her husband Hajoe Moderegger under the name eteam. Their projects have been featured at PS1 NY, MUMOK Vienna, Centre Pompidou Paris, Transmediale Berlin, Taiwan International Documentary Festival, New York Video Festival, International Film Festival Rotterdam, the 11th Biennale of Moving Images in Geneva, among many others.

This post may contain affiliate links.