[FC2; 2017]

[FC2; 2017]

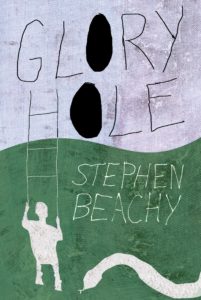

On the back cover of Stephen Beachy’s Glory Hole, the synopsis concludes, “the novel also serves as a version of the I Ching, meaning it can be used as an oracle.” On Beachy’s website, he gives directions for how to consult the book as a prophetic text, and each of the sixty-four chapters is linked to one of the traditional hexagrams (which are also the accompanying images before each chapter). Even after having finished the novel, I couldn’t quite put my finger on what he was getting at. There didn’t seem to be an explicit connection between the novel’s content, a Bay Area community teeming with characters and caricatures from the 80s to the early 2000s, and the I Ching. So I set out to find the connection by consulting the novel myself.

Before I could even throw the coins, I needed to think of a question. I flipped around in the book, looking for question marks, something to resonate. It seemed like the question should come from within the book, not from me. I wanted to learn something about the book itself, for the book to loop around its own prophecy.

I found: “Melvin says, as if to himself, What is a book for?”

Of course, this question seems obvious, or trite, but for me, at this moment, it’s important. The characters in Glory Hole have pictures on their refrigerators of civilian casualties of U.S. drone strikes, children with missing limbs. A character is waterboarded—or at least it’s imagined that he’s waterboarded, in detail. Amish children are shot in a schoolhouse. There are junkies, punk bands, pornographers, liars. A four page list of types of rape. AIDS, Disneyland.

This world is our world, and a lot of it is a mess.

Plotwise, the center of the novel from which much of it radiates is the mystery of a young, popular author named Huey Beauregard who may not exist at all, closely echoing the stories of Anthony Godby Johnson and JT Leroy. (In fact, Beachy played a role in revealing the Leroy hoax.) Melvin joins Philip, Felicia, and a group of their friends in puzzling out the truth behind Huey’s writing and public persona. This question of authorship / authenticity frames Beachy’s novel boneyard, purported to be written by the Amish teen Jake Yoder who is mirrored by the character Amos in Glory Hole. The act of writing a book, reading a book, putting truth into a book or wanting truth out of it, is all over this novel and its relationship to Beachy’s other work.

Melvin, who asks “What is a book for?”, is a voice of naïveté in the novel: he’s young, a runaway Mormon living in a squat in Oakland, and he is always questioning, most often his sexual desires. His voice gives the question the kind of innocence necessary to make it worth considering, or reconsidering. Like, it can’t be trite if he’s the one asking it.

And, a book like Glory Hole that is so long (495 pages) and really heavy, literally; with overlapping narratives and characters, blurs of reality and invention; a sprawl of a book with a vague narrative and unmappable plot: What is it for? What does it contain, and what tentacles does it stretch into the world?

I followed the directions from The Everyday I Ching by Sarah Dening and threw three coins six times. I ended up with hexagram 40 that then changed to hexagram 16. The directions on Beachy’s website led me first to discover the current situation in Part III, Chapter 3, then to Part II, Chapter 8 for future possibilities.

Hexagram 40

According to The Everyday I Ching, hexagram 40 means “Release from Obstruction.” There was a blockage, and now one may let go and/or make progress.

Part III, Chapter 3 is one of my favorites because things aren’t what they seem. There are phone calls and dial tones, two bridges that are worlds apart, a bay and a river, underworlds, mirrors, doubles, and doors. Who is sane? What is real? “It’s really raining now. A downpour of auras and meanings.” Three moments in this chapter stand out as potential responses to “What is the book for?”:

- “A sentence is a period of time when you are in a particular place. You live within that space and that time. You live within the sentence.” Of course, this is like reading: We are sentenced to be in a space, alone and quiet, in the book through its sentences. A novel like this keeps us there: it is long; the plot is purposively muddled; we’re treading water.

- In this chapter, Philip, a writer and weed dealer, has gone to Iowa to write a piece on a shooting at an Amish schoolhouse that has killed several children (a retelling of an actual event). He befriends a teen, Amos, who has left the community, in hopes that he can connect Philip with the shooter’s son and relatives of the children murdered. Philip and Amos are in an abandoned building, and a mother of one of the children is outside on the bridge over the river. She won’t speak with Philip, but Amos offers to ask her a question for him:

“One [question] is probably enough. She sees things. The river’s like her mirror. It’s all there.

Ask her where it’s going, Philip says.

You know that already. Everyone knows that already.

Then ask her what it’s for. I don’t know that. Nobody knows that.”

Strangely, Philip’s question echoes our question, Melvin’s question. Is “it” the river? Life, the book, the shooting? Amos returns with a few answers from the mother, one of which is “that the door to the invisible has to be made visible . . . it’s the only place left for us to go.” The book is a doorway into a world we cannot see here. Not a mirror, but an opening.

- Finally, Amos has shared with Philip a book-length collection of his stories. Amos begins to break down, calling the stories “evil.” He throws the papers into the fireplace and runs out of the building. Philip grabs the manuscript out of the fire, and it has “a crater of charred blackness right through the middle.” The book is a black hole.

The progress to be made, then, is to be sentenced to the book, go through the door, dive into the black hole.

Bibliomancy

Before I consulted the book as oracle, I knew where to find the answer to the question. I went to my shelf and pulled out From the Book to the Book: An Edmond Jabès Reader, translated by Rosmarie Waldrop. If anyone knows what a book is for, or who has really dwelled in this question, it’s Jabès.

When I opened it, an old bookmark was between two short passages, one titled “The Loop” and the other “The Hole.” “The Loop” begins, “‘One of my great fears,’ said Reb Aghim, ‘was to see my life round itself into a loop without being able to stop it.’” Glory Hole’s characters move through narratives and around each other in helical multiplicities. Are they looping downward, hellward? (A repeated phrase in the novel is “down below,” calling out to Leonora Carrington’s memoir of her institutionalization.) In the book’s final third, Ralph, a porn/horror film director, says, “The glory hole is really a hell mouth anyway.” I wouldn’t call the book a hell, but an acceptance of and a description of communities within our living world as hell.

Now here is the middle section of Jabès’ “The Hole.” For many of the characters —Melvin, Felicia, Philip, Amos, Bob… or for Sarah, the woman who invented Huey Beauregard—I think this passage holds an answer to our question (though really what I’m learning is that the answer is everywhere, on each of Glory Hole’s 495 pages). And perhaps this is another kind of prophecy: one hole speaking to another:

The book is a labyrinth. You think you are leaving and only get in deeper. You have no chance of running off. For that, you must destroy the work. You cannot make up your mind to do that. I notice your anxiety mounting. Slowly but surely. Wall after wall. Who awaits you at the end? Nobody. Who will leaf through you, decipher, love you? No doubt, nobody. You are alone in the night, alone in the world. Your solitude is the solitude of death. Another step. Somebody will perhaps come and pierce the wall, will find a way out for you. Alas. Nobody ventures here. The book bears your name. Your name clenched like a fist clenched on a sword.

Ridiculous, on your belly like this. Crawling. Drilling the wall at its base. Hoping to escape like a rat. Like the dark in the morning, on the road.

And this determination to stay upright in spite of being tired and hungry?

A hole, just a hole,

the chance of the book.

Hexagram 16

The second hexagram is meant to be a way of looking at the future, beyond the initial reading. Hexagram 16 is called, in The Everyday I Ching, “Thinking Ahead,” and on Beachy’s site, “Enthusiasm.” Comfort, confidence, and harmony are read here.

In this chapter, Geordi, a translator and scholar of obscure ancient Arabic texts, finds himself in a transient encampment upon a garbage dump. He sits with a group of men inside their tent, and Geordi, like Philip in the above scene, is both bewildered by and accepting of his situation (neither unlike Alice who participates in but continually questions her new, confused space). One of the men thrusts a notebook into Geordi’s lap.

Take it, he says. Take it with you and study it. I have it memorized anyway, but you can use it, you can use it to mobilize the insurrection, when the time is ripe, tonight, tomorrow…

Every insurrection is a part of the same insurrection, the man says. One insurrection spread out across space and time like music. Every insurrection shares a rhythm, a kind of vibration. Feel it. Feel it coming, feel it inside you, not someday, but right now…

I first read these lines darkly. The scene is ominous, and the call to violence unnerving. An insurrection in response to what? Drone strikes, water rights, healthcare, police brutality?

Hexagram 16, though, suggests a kind of hope. The insurrection is like music, and it “shares a rhythm” with other insurrections. This notebook is a tool for uprising and a pulse among the other texts internal to the novel as well as all other books. The hope there is in the power of the book and the ability of books to make change. But, I don’t think I’m wrong to read the lines with suspicion because there is never any indication of what kind of change, for good or for evil. Like Philip asking about the river, I want to know where it’s going. Returning to the previous section, Amos thinks his book has power:

Amos explains calmly and quite clearly that he is the one who made the murders happen.

It’s because of these stories that he wrote, which are like magic. The stories became real. The shooter received them as a kind of transmission or a kind of writing in the atmosphere… [T]he stories… come directly from hell.

These books are capable of action, their authors think, prophetic — like the I Ching. Jabès says, “The book bears your name.” How does what we read come into our lives? What real power does a book have to predict (open doors) or to depict (reflect back)? By putting one prophetic text against another, I might have held up a mirror to a mirror, creating endless openings, or, I guess, a hole.

The Amish mother says that the “invisible has to be made visible.” Glory Hole continually shows events and environments that are both authentic and upsetting. But it does this in honest conversation with its own form, surprising length, endless stories within stories, films and references, other books, dreams. That’s what artists and writers do: they show the world, in all its pasts and futures, infinitely, as itself unbounded.

Kelly Krumrie is a PhD student in Creative Writing / Literature at the University of Denver. Prose is forthcoming from or appears in Black Warrior Review, SHARKPACKAnnual, Sleepingfish, Shirley Magazine, Your Impossible Voice, and others. She is currently the translations editor at Denver Quarterly. Links to her work can be found at kellykrumrie.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.