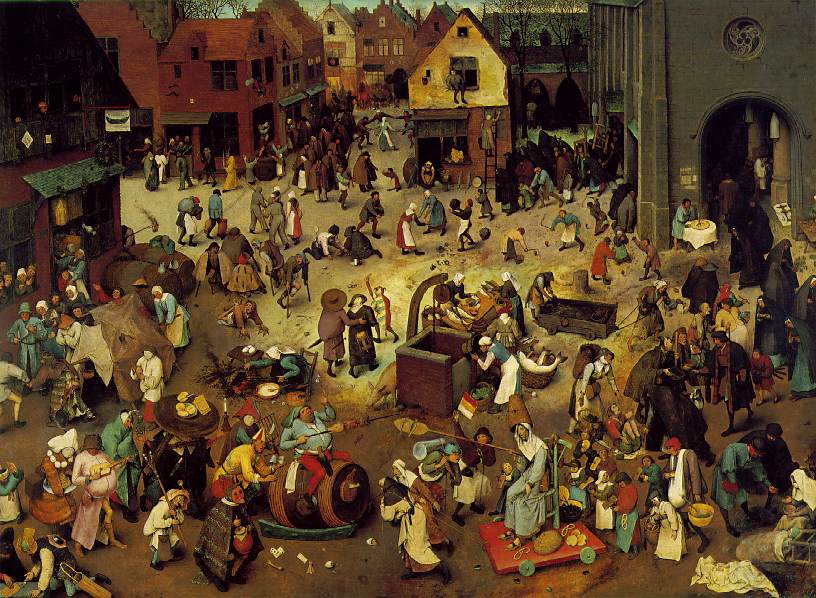

Pieter Breughel the Elder, Carnival’s Quarrel with Lent (1559)

This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #7. To help us continue to pay our writers, please consider subscribing.

Alas, alas for Hamelin!

There came into many a burgher’s pate

A text which says, that heaven’s Gate

Opes to the rich at as easy rate

As the needle’s eye takes a camel in!—The Pied Piper of Hamelin: A Child’s Story by Robert Browning, 1842

Steeped in folkloric memory, the medieval “Pied Piper” perhaps received its most popular English rendition from Robert Browning. Browning’s verse, among other innovations, singsongs the discord in Hamelin, the political backdrop of which is all too familiar. Two modern villains, the Mayor and the Corporation, are responsible for the town’s rat problem. The townsfolk charge both with negligence. Without populist pressure, the narrative suggests, there’d be no disharmony to speak of, let alone resolve:

At last the people in a body

To the town hall came flocking:

‘Tis clear,’ cried they, ‘our Mayor’s a noddy;

And as for our Corporation—shocking

To think we buy gowns lined with ermine

For dolts that can’t or won’t determine

What’s best to rid us of our vermin!

The tale’s mainstay arrives soon to the scene: A vagabond musician who happens by a town undone by rats and, by a hap stranger, rids them of their pestilence with a few whistles of her pipe. Promised a bounty, the piper leads the rats to water, drowning them. Social order is accordingly harmonized. But when the Mayor and the Corporation do not service the town’s debt, the piper again wields this inexplicable power and trances the children out of town, stripping it of its posterity, never to return.

Leaving Browning’s modern innovations to the side, the fundamental mystery remains: What of this itinerant musician with her uncanny ability to sew and un-sew the social and political fabric as effortlessly as breath itself?

•

The musician’s social and political role, her twin power of composing and decomposing order, is not so inscrutable to Jacques Attali, a French economist who in 1977 published a Marxist history of music titled Noise: The Political Economy of Music. In it, Attali esteems Pied Piper narratives as “the best and most enlightening examples of myths about music.” A serviceable symbol of Attali’s Noise, the Pied Piper gives metaphoric sense to Attali’s strangely metaphysical economic theory.

“Music,” Attali claims, “is prophecy.” An audible vision, “its styles and economic organization are ahead of the rest of society.” The temporal and immaterial features of music have long marked its unique aesthetic, but, for Attali, they imply that music “explores, much faster than material reality can, the entire range of possibilities in a given [political and economic] code.” Like scientifically predictive numeric models, music “makes audible the new world that will gradually become visible” to “impose itself and regulate the order of things.” Not unlike the Pied Piper, and as Plato well knew, “musicians, even when officially recognized, are dangerous, disturbing and subversive.” Musical creations “herald the future.”

The aesthetic peculiarity of music—its ecumenical spirituality, its kinship with number, and its subversive power—raises the possibility of its unique material production. Attali’s historical dialectic presents music as ever-presence, both annunciatory and world-defining, while music’s counterpart, noise, creatively destroys worlds, shaping reality anew. By extension, music’s material production is a window into the economic whole and a privileged set presaging the total economy. Simply, the way musicians and the music economy go, so go other occupations and economic sectors.

That music is prophecy, especially in economic matters, is hardly self-evident. However, since its publication in 1977—a crucial year in American DIY music—Noise’s artful economic theory has landed certain of its high-flown predictions. Attali devotes the last third of Noise to what he calls composition, a mode of the economy “beyond exchange,” emerging out of the commodity economy. “The bulk of commodity production then shifts,” according to Attali, “to the production of technology allowing people to create the conditions for taking pleasure in the act of composing.” Within this new composition economy, music is produced “as self-communication,” as a “noncommercial act.” Writ large, composition proposes “a radical social model” wherein participants are “capable not only of production and consumption, and even of entering into relations with others, but also of autonomous pleasure.” To be sure, if we see the composition economy at all, “we can see in the makeup of musical groups, in the creation [and use] of new technologies . . . an outline of what composition can mean: each person dreaming up his own criteria, and his way of conforming to them.” A familiar DIY ethos, indeed.

In this overdetermined scenario “beyond exchange,” your creative self can have it all, previously unthinkable in the capitalist marketplace of commodities: inalienable ownership over your creations, even near total indulgence in their creation without risk of unsocial solipsism. Composition, for Attali, is “personal transcendence” at its most illimitable. While this seems outrageously fantastic, two contemporary developments make Noise’s dialectic worth heeding. Our economy, of course, has not emerged entirely out of a commodity economy, but de-commodification brought the mainstream music industry to its knees at the turn of the century, and, doubtless, something like composition informs what we today call DIY, which was around in ’77 and is nearly ubiquitous today.

To compose a living, a sense of self, and a society by whatever available means is a good shorthand for both the DIY ethos and Attali’s notion of composition. By elaboration, we certainly can identify a composition economy: Consumer technologies have proliferated do-it-yourself projects and learn-it-yourself skills, while, broadly speaking, owning—if not mastering—technologies is requisite for employment. Predicated on creativity, learned skills, and voluntarism, DIY music files under this composition economy, sure, but it’s of a sort with any authorial or copyrighted work, freelance-based new media, Patreon, craft culture, the pop-up art world, and the gig economy. That only some of this work is compensated, while perhaps a majority is recreational, redounds to Attali’s predictions. However, it’s important to note that Attali thought a compositional mode of the economy would be emancipatory, if only because, as any “composer” in our gig-economy can tell you, it has not been.

Noise provides a genealogy of this composer, DIY ethos, tracing a historical through line: “Composers,” Attali explains, “are rentiers.” Attali’s notion of “rentier” is particular. Composers, as Attali defines their “strange situation,” are historically a category of worker who “succeeded in preserving ownership of their labor, in avoiding the position of a wage earner, [and] in being remunerated as a rentier who dips into the surplus value.” Outside traditional wage labor and salaried employment, rentiers’ “income is independent of the quantity of [their] labor,” Attali explains, and, instead, these workers “depend on the quantity of demand for that labor.” Plying their creative and intellectual means, a composer seeks income from patrons, who, in more advanced stages, profit wildly from their work. Beethoven’s modest patronage relation with the Catholic Church turned on this economic form. This arrangement applies later, from the 1930s on, to meagerly compensated songwriters, producing hit parade singles for record executives who took the lion’s share of surplus value. In fact, throughout the twentieth century, the music industry, both mainstream and independent, essentially perfected this particular rentierism by courting found talent from small- to large-scale patronage.

Today, many economic relations resemble this mold, some more lucrative than the pauperism of traditional composers. But Attali had not considered the underlying precarity of composition as a form of irregular employment. In the US, 94 percent of job growth in the last decade has been in what economists call alternative or precarious work, all rentierist in Attali’s sense: temporary, non-wage, unsalaried, contract, or freelance work. As economist Guy Standing has pointed out, this “new economy” is really an “on demand economy,” wherein workers parlay their learned skills and purchased technologies to meet demands of at-will work. As capital and wealth have become concentrated, so too has corporate ownership of the vast technological apparatus producing tools and occupations.

While the new economy’s aesthetic of an economy of creators—of composers—is the natural look of DIY’s ubiquity, the attendant economic insecurity is hidden from view behind the flashy marquee of the “creative class.” Without built-in employee benefits or protected employment, this new composer working class—what Standing calls the precariat—market their DIY skills as the very essence of their labor value. As the commodity economy contracts and automation winnows the labor market of “unskilled work,” skilled creative work fares no better when insecure workers are remunerated as paupers. If rentierism of this sort is the archetypical economic type of musicians, then, increasingly, a significant portion of today’s laborers are “musicians.”

In a purely technical sense, the means of composition—not the means of production themselves—are in the hands of those dispossessed of wealth and capital. This is the crucial way the musical economy prefigured the broader one in our political economy. By crafting, producing, and broadcasting individual or collective projects, a composition working class jury-rigs share economies and drafts pop-up societies—they “make do” in the fullest sense. Culturally enriching a world hollowed out by the loss of collective wealth, composers stylize our troubled and seemingly unsustainable situation. If we take our cue from Attali, by updating his history of the production of music, what can we discover about this relatively new and unmistakably precarious economic reality?

After all, today’s musical production is itself markedly polarized, with pauperized DIY musicians working amid the wreckage of a collapsed music industry and high-profile musicians—really, they are celebrity entrepreneurs—making money from basically everything but their music. The decades since 1977 have been tumultuous for music in the US, and the strange unfolding of DIY, technology, and commerce—with the dramatic collapse of the US’s billion-dollar music industry—has been complex and foreboding.

So much is the DIY ethos of this horizon that DIY music is co-ordinate with the political limitations set by our current order. The earnest calls to rehabilitate the Reagan-era punk movement, militant post-punk situationism, and other insurrectionary musical legacies are a testament to the prevailing desperation for a new political order and the creative destruction of musicians. Admittedly, these calls seem imaginatively bankrupt, if only because these last few decades have left us literally bankrupt. No less, if Attali’s theory has any credit, music’s current political economy might yet signal society’s next horizon. Upon a closer look, contemporary DIY music, still considered a potent site of radicalism, might actually practice ways of breaking out beyond today’s bleak horizon.

The ground covered in Attali’s Noise is no longer speculative: Tech consumerism affords the technology to build worlds. We live the composition economy, and its power of creating society is distinctly set off against the destabilizing economic disenfranchisement of the majority. Attali’s obscure 1977 title ultimately sounds questions that go beyond the cui bono of who profits: If the composition economy—the “new economy”—has bestowed us with the creative and destructive powers of the Pied Piper, then what of the children? Who is leading whom? Most importantly, where to—and to what end?

•

December 2017 marks the first anniversary of the fire that consumed Oakland’s Ghost Ship DIY venue and asphyxiated thirty-six show attendees. In its wake, DIY venues across the country have been shut down, precipitated, in part, by the online alt-right, who seized the opportunity to “crush the radical left.” In New York alone, over 20 percent of small local venues have closed, including the beloved Shea Stadium, the digital archive of which still speaks to DIY’s culturally productive possibilities. While this tragedy and the ensuing crackdown are only the most recent episode, the saga of DIY music has always been one of survival, operating within and without authorized establishments, finding resourceful ways to stay alive.

From 1974, when CBGB owner Hilly Kristal told the Ramones, “the only way you can play here is you have to do only your own music,” the following four decades would prove DIY music to be a thoroughly resilient community. This is due, in no small part, to its longstanding alternative political economy, so despised by the modern alt-right.

It’s tempting to mark Kristal’s response to the Ramones in ‘74 as the beginning of DIY music in America for many reasons, the bulk of which miss the mark. It’s not because the Ramones were underground, played within their limited means, or are said to have codified “punk”—DIY’s signature genre. In fact, nothing about them makes it so. After all, plenty of other counter-cultural bands, perhaps enamored of the Beatles’ performance on The Ed Sullivan Show in ’64, procured instruments and spent a hellish and unrewarding decade trying to catch the attention of major record labels. The difference between two bands from Michigan—the Stooges and the all-Black band Death, both admittedly spurred into music by the employment crisis—tells the gamut of outcomes. What makes Krystal’s response an inception of sorts is that CBGB was representative of a country-wide development of small bar-venues patronizing original musicians. This decentralized musicians’ economic relationship from major labels and their opulent studios, outsized concert venues and festivals, and TV’s push-pull fascination with youth culture toward multiplying local, relatively sustainable, and ultimately makeshift economic hubs.

Originating in the previous decade’s counter-culture communalism but culminating in ’74 at CBGB, a punk substrate had seeded and grown across the country’s vastly connected hubs such that punk’s hubbub became commodifiable. Patti Smith, though, hardly counts this time in economic terms. She views the heyday of CBGB as primarily a “community of poets”—poetry being the most un-commercial of art forms. But by 1977, the year post-punk bands Television, Talking Heads, and Suicide released their first records, commerce had peeled back the earth, uprooted, and prepared most of CBGB’s underground acts for mass consumption. If punks who produced records in ’77 are remembered as post-punk, it’s partly because of DIY music’s deeply seated ambivalence toward large-scale commerce.

Rather notoriously, when a Canadian talk show host in 1977 beseeched him for punk’s definition, Iggy Pop articulated this ambivalence: “Punk rock is a word used by dilettantes and heartless manipulators . . . it’s a term that’s based on fashion, style, elitism, satanism, and, everything that’s rotten about rock ‘n’ roll.” For Pop, the rock ‘n’ roll of a previous generation was free and easy; punk, forged in the seventies economic crisis, was hard-earned, laborious: “This is serious business to me do you understand? . . . I’ve worked very hard for a very long time to try and make something that’s beautiful enough so that I can enjoy it and so other people can enjoy it.” The televised celebrity setting is inseparable from Pop’s earnest, if unsettled, point: What the previous decade of popular, commercially lucrative counter-culture lacked in homespun, gritty ethos, punk soon found to be its most salable feature. If, in the period of ur-punk prior to ‘77, bands and bars were a marriage of inconvenience—banded together by economic downturn—bar bands presented a convenient market for the record industry. That the music industry’s eventual favor was outsized but felt deserved expresses all of punk’s contradiction.

In the eighties, this contradiction would serve as the material breach, cleaved open by the punk posture, wherein independent record labels and DIY music, enabled by increasingly cheap home recording technology, would coordinate in the shadow of larger conglomerates. The quintessential DIY record label out of DC, Dischord records, started in 1980 with a band-fund-turned-investment-capital totaling $600. Eventually producing the likes of Fugazi and Minor Threat, whose respectively dogged work ethics inform a substantial portion of their legacy, Dischord was one in a coalition of independent record labels like Touch and Go, 4AD, Subterannean Pop. If a mutually founded bar-society provided a relatively equitable DIY venue for bands, these labels provided relatively equitable means to produce and distribute commodities. The artist-owned Dischord still exists, and its sustainability has all to do with their unusual business practice, one Dischord’s founder Ian Mackaye stands by: “All bands on Dischord have the same basic [non-contractual] agreement with the label: They’re advanced a certain amount of money to record an album and produce a record cover; once those costs and the costs of manufacturing the record are recouped, Dischord and the group split any profits.”

MacKaye appears to have resolved that, if musicians’ economic relationship was one of patronage, then Dischord would act as an enlightened patron by founding its terms on mutuality, effectively liquidating the notion of patron altogether. Even in the indie world, Dischord’s model was not exactly normative, as other indie labels have been variously less generous to their artists or have conceded to corporate buyout, but it was a viable economic alternative to mainstream record-making. Indeed, this alternative was the natural extension of Mackaye and co.’s egalitarian political beliefs. Their model is the mold of today’s DIY musical economy, which adheres as closely as possible to tenets of collective ownership, principled inclusivity, and resourceful situationism. Based not in the largesse of capital but the largesse of spirit, DIY music’s political economy, which has maintained the communalist vision of punk’s network of venues and mutual ownership, has remarkably weathered the headwinds of digital innovations.

At first, digital innovations like CDs and digital video were a massive boon to the musical economy. After all, 1982 was a recession year for the industry, but it was also the year compact discs were invented and of Thriller, eventually the best-selling record of all time. The first music video aired on MTV only a year before. CDs, which were “the fastest growing home entertainment product in history,” and the music videos of MTV would lay the groundwork for a massive music industry. These technical developments marshaled behind Jackson’s rise to the top of the pop music world, and, more broadly, they sustained the industry until the end of the century. In fact, the nineties’ tech-induced economic boom was evinced most dramatically by a globally sprawling corporate music industry, processing multi-media musical production in increasingly efficient and profitable ways. The movement of local DIY to large-scale patronage that had turned found punk acts into defanged “alternative music” would process hip-hop into the premier commercial genre of the nineties in a quarter of the time.

Driven by these innovations and an outright rapacious industry, nineties alternative music—the large-scale “lifestyle” analog to DIY punk’s small-scale alternative—eventually went gangbusters. Even Fugazi was offered not one but multiple million-dollar deals. But, as Steve Albini once pointed out in his ’93 article “The Problem with Music,” the industry was actually grifting a market saturated with bands. The situation meant, hypothetically, a “pretty ordinary” but “pretty good” band would, after all the smoke and mirrors of production, merchandising, and distribution, turn “$4,031.25” of profit each, while the industry as whole profited to the tune of “3 million.” So sums Albini, “The band members have each earned about 1/3 as much as they would working at a 7-11, but they got to ride in a tour bus for a month.”

The swindle could only go on for so long, and the other shoe finally dropped when the internet helped decommodify music. Albini has since argued that the “internet has solved the problem of music,” at least as he had defined it. Be that as it may, the music industry had sold various lifestyle options as so many forms of liberation. This kind of liberation-through-purchase still has a hold on consumers. What ultimately matters, however, is that the music industry consolidated its capital holdings and left a whole generation of composers duped and fleeced and a whole generation of consumers all worked up with nowhere to go.

If Y2K proved apocalyptic for anyone, it was the large-scale music industry and retail record stores, but before the century’s turn, these large-scale practices provide a good object-lesson for when an entire industry depends on a substratum of composers. Decommodification has meant that behemoth music companies have experienced escalating losses in music publishing, resorting to brand management and ad revenue as the new profit-makers. The music industry’s capital strongholds are inertial, as corporate reps scheme on celebrity-dependent marketing strategies, ad shares, and the performance of large-scale spectacle to maintain their margins. These practices are essentially life support for a dwindling model. Decommodification has forced a change in mainstream business practices, from larger- to smaller-scale, turning back the dial on their previous growth. But decommodification has had far greater consequences, the most important and immediate of which is the radical suggestion that music should be free for consumption and free of patron ownership.

The new model of musical consumption, digital streaming, has so changed the landscape of music’s profitability that it’s changed copyright law, and, accordingly, since 2015 the music market share of independent rights ownership in the US has increased from 1.7 to 37.3 percent. Spotify, essentially a digital branding device that happens to function as a musical archive, remains unprofitable both as a company and for artists and labels. Bandcamp is a digital commons for independent musicians. It is, in fact, entirely possible for a musical artist to share their music online without exchange whatsoever. Monetary return for music qua music is a remote possibility for the large majority of musicians. Still, as music qua entrepreneurial branding creates all the profits, if only for the technological ease, there are more composers than ever. The more artful individuals there are composing music independently, the less they have stake, share, ownership, or, finally, any sympathy for a mainstream industry forestalling its demise.

Meanwhile, old school DIY musical production on the level of Dischord continues within its small-scale exchange economy, though digital production has made its presence felt there too. A sign of the liminal times: Just this year Chance the Rapper was the first independent artist to win a Grammy for a mix tape he distributed for free without any label involvement. Insofar as “industry insiders” still exist, they look to Chance as the future. The future of music appears to belong to, on the one hand, independent composers and on-demand economies and, on the other, brands whose advertisement value is what remains of the industry’s profitable cultural output. The mainstream music industry has been ousted from its large-scale commercial agora and no roadmaps chart a viable odyssey back. Given the history of its deeply exploitative practices, good riddance.

But, as Attali pointed out in ’77, the centrality of independence and the labor value of composition is a return of sorts for musicians. In accordance with their rentier status, composers have always already been independent of commerce, though their unquantifiable labor may be “trapped and expressed in commodities.” Attali went so far as to claim that composers historically were “outside capitalism,” somehow “at the origin of its expanse.” From this ideal perspective, that the musical economy has emancipated composition from commerce is not at all surprising. But it hasn’t necessarily been emancipatory for the composers.

Having ostensibly sensed this tension within Attali’s work, the late Mark Fisher, in 2010, was prompted to write, “Jacques Attali once argued that fundamental changes in the economic organisation of society were always presaged by music. Because, as a result of downloading, recorded music now seems to be heading towards decommodification, what does this suggest for the rest of the culture? And are we yet to hear the impact that the financial crash and its aftermath will have on musical production?”

To be sure, this is exactly the question to ask.

•

Classically, the nineteenth-century rentier was a luxuriating aristocrat whose asset-dependent income was independent of their labor because they didn’t labor. Their income was unearned, come to by inheritance, land rent, or interest on debt they owned. Our current form of capitalism has created what economists call a rentier society, when an economy’s sole function is the upward redistribution and consolidation of wealth for the aristocratic rentier class. Today, this aristocratic rentier class is more legible if they are identified as the investor class.

Of all employment relations, a composer-worker under rentier society rather expediently facilitates this upward redistribution since she is paid on demand, in decimals of the bottom line. Given the significant increase in tech-based creative work, the winnowing of “unskilled labor markets” by automation, and the forthcoming technological utopia depicted by the left and the right of a post-work future, our rentier society is slated to become a society of rentiers. In the long-term, the rentier of the nineteenth century is possibly going to become the normative type but with a crucial twist: It will likely be a norm rent in half by polarized economic inequality. The “new economy” of non-traditional workers already turns on a contradiction that inheres in rentier society: Determined by debt and ownership, all “creative types” will likely be paupers or aristocrats.

While the fully fleshed form of this economy is still in the offing, economists have increasingly speculated about these nearby prospects since the financial crisis. Accordingly, the exploited rentier composer is the more local and individual valence of what contemporary economists, such as Michael Hudson, systemize as rentier capitalism, or debt capitalism—a development unforeseen by both Marx and Keynes, where industrial capitalism, built by labor and industry, is supplanted by financial capitalism, a global, post-industrial, debt-based system dominated by the Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate (FIRE) sectors. This development was imperceptibly underway in 1977, but its unjust contours are unmistakable today. The top-heaviness of our economy is one consequence, but the abuse of this development has been rightly faulted for the economic collapse in ’08.

In this system, the wheels of capitalism—banks and other financial institutions, major industrial producers, special interest lobbies—are spun by the motor of international governments for profitable survival. These big business organs are often maligned as “rent-seekers,” but, rightly so, since they—and their governmental counterparts—are more accurately “kickback seekers.” The role of administrative government under rentier capitalism is consequently demoted to underwriting private interest. Contrary to what Keynes had expected, instead of committing “collective euthanasia” by taxing their profits, the aristocratic rentier class has avoided its tax obligation altogether and absconded with our collective wealth. This rigged for-profit welfare system has supplanted, even precluded, any commitment to traditionally understood public welfare.

This high-power collusion has been well documented, but an overlooked consequence of rentier capitalism is the transformation of the underclass. Indebted workers’ class character has devolved into a variegated collection of differentiated, individuated “rent-seekers,” beholden exclusively to their “private interest”—you know, stayin’ alive. So far as debtors petition the owners of production and capital for income, they are not dissimilar—the word hustle is apt here—from how creditors petition the government. Indebted workers compose their lives and cultivate their talents in the hustle for on-demand, skilled labor, while creditors hustle taxpayers for governmental trade-offs. In a sense, there are increasingly two “rent-seeking” classes: the debtor precariat seeking basic income and the creditor aristocrats seeking unearned income. All economic actors thus sing the same tune: With the near total liquidation of some notional public interest, private interest has a mandate to seek the means of reproducing itself, a bleak horizon for human activity that we’ve yet to fully reimagine. Limiting human activity to this horizon is something like an economic law under technology-rich austerity.

Since technological proliferation is most profitable, techné is the means, the aesthetic, and the short-term end of today’s economic production. Hailed as the vanguard of the creative class, the tech industry continues to outpace other sectors, and, while consumer technologies might deliver modern pleasures of digital consumption and production, the resultant economic precarity of most individuals is unmistakable. Our technology-enabled compositions are the window dressing of our fundamental economic precarity. Tech-capitalists have so dramatically shaped the means of production that they’ve transfigured workers and their means, profiting the rich and the rich alone. The world is truly composed by globe-trotting tech-capitalists, who have themselves absconded untaxed with our collective wealth. Our private compositions, afforded by massive technological output but done by ourselves, seem to matter very little when, between our debt and the cost of living, we can’t afford anything more than a per diem.

Or, to turn in the round of this paradox, is it not precisely that they matter a great deal? Is it not that our private compositions, in the end, serve a veritably public function? Consider the above saga of DIY music in America. At its best, the political economy of DIY music is an evergreen, syndicated society of non-traditional workers, who band together on political principle and creative impulse, to compose a fair, inclusive, and beautiful world. Even as many musicians work other jobs for their substantive income, they delight in truly un-coerced musical labor, in their own and in their comrades’. So potent is this collective economic practice that certain practitioners have outlasted the monstrous global music industry and even served as a more sustainable model of mutual exchange. The very technological innovations that have made the nouveaux riche into aristocrats are the ones utilized by pauper rentiers to create a welcoming and equitable alternative economy. If, in the US, there exists a fungible approximation of Murray Bookchin’s ideal of local, libertarian-socialist, self-governing communities, networked across a country and independently operative of the state and capitalist relations, grassroots DIY music has been a somewhat unwitting attempt and, possibly, a model.

•

Returning to Attali’s favored musical myth, when the Pied Piper led the children out of Hamelin, it is said, she led them beneath Koppen Hill, sometimes construed as Calvary Hill. Julian Scutts, in his comparative study of the Pied Piper, suggests the likelihood that Browning’s “revamped story expresses deep misgivings concerning the rise of a new wage-earning class that attended the emergence of money-based non-feudal capitalism and unrest, particularly among the peasant population.” On these terms a pliant mythical metaphor appears in the difference between Scutts and Attali’s interpretation of the Pied Piper.

Whisking the children away, dishonored by an unpaid debt, the Pied Piper led Hamelin’s posterity beneath the sign of Hamelin and the West’s post-feudal future, capitalism. Whether it is a bad sign it is hard to say. Quite evocatively, Koppen Hill is variously interpreted as both a proverbial heaven and the literal jaws of hell. Browning’s version, for instance, presents Koppen as potentially a Paradise. No less, what is the resultant function of modern political economies but to make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven? For that is precisely what is at stake today.

Wealth inequality in Keynes’ time was a going concern of his, and, appropriately, he deemed it a societal problem rather than a wonky policy problem. He transparently saw the existential cost of wealth inequality, which led him to defend the need for “direct taxation.” He was so certain of his solution—the “euthanasia of rentiers” by taxation—that he famously quipped about how the collective suicide of the modern capitalist aristocracy “will need no revolution.” Since 1936, there has been neither voluntary suicide nor revolution in its stead, alas. And, as of this very writing, a contemporary batch of aristocratic, tax-dodging billionaires are seeking tax cuts from a billionaire president, on the strength of, if not a promise, mere inertia of a historically militant and rapacious billionaire class.

If the Pied Piper, betrayed by the Mayor and Corporation, condemned Hamelin’s future city-state by leading its children into an uncertain new future, then such is the imminent decision of the new pauper class. Where to now, we might ask, and how? This is not an idle question. Not unlike the Mayor and Corporation, the billionaire class—especially the tech-capitalists shaping future reality—and its governmental counterparts owe us what pink tide socialists in Latin America used to call “a social debt.” As if overrun by rats, society is becoming undone, and it’s their fault. Just as in Hamelin, the very things we buy are lined with vermin. Even as we contrive solutions through alternative societies and alternative economies, the Mayor and the Corporation preside.

No doubt, until the disparities and injustices are resolved, we retain the powers of the Pied Piper. After all, as evinced by the last four decades of DIY music, we already use the technology of tech-capitalists toward proto-revolutionary ends, even small-scale, revolutionary societies. Already something like a composition class is acting not unlike a class. The same revolutionary ends are pursued, albeit without totally conscious coordination, by a diverse coalition of independent digital and print media, activist organs on social media, and jury-rigged pop-up societies across the country, whether by holding meetings and talks, plying their art, or banding together in purposively intersectional company. They are living, as Simone de Beauvoir once put it, as if the revolution has already happened. However, as the aristocratic “creative class” crafts the future in its image, it is high time the pauper “composition class” start consciously thinking and acting together as a class.

If we want society to amount to something more than artful lifestyle opportunities, as the faux-revolutionary music industry sold us throughout the last century, we’ll need to make inroads into the citadels of capital. Until a horizon dawns when we control the means of production, the means of composition might offer the relief of commonly composed society. But it’s the former that counts.

Alex Colston is a musician, editor and writer living in Brooklyn. His band is called darkturn. He is currently an Editorial Assistant at Basic Books, a freelance Researcher at Pitchfork, and a contributor to the music review website, Post-Trash. You can harangue him on twitter @re_colston.

This post may contain affiliate links.