The “overstory” of Richard Powers’s title is a term for the canopy of a forest, the foliage at the top of the trees. Powers has sometimes been criticized for being a “top-down” novelist, one who presents characters from the high or long perspective of history, science, or music. These critics carp that his often highly intelligent characters are not human, don’t live and breathe and feel for each other. In The Overstory, Powers twits those critics by presenting — with his usual scientific brio — trees that live, breathe, and signal to each other, exist in a “social” relation with other trees and the biosphere that depends on them. Trees were exhibiting qualities of animal life long before the human story began and will be here long after the human story is over, the latter hastened by our suicidal deforesting of the planet. Powers knows, and a psychologist in the book says, that humans need “good stories” to be persuaded by scientists’ alarms, so Powers creates a band of varied and lively characters with back stories and understories to make his novel a “bottom-up,” as well as a top-down, fiction, one that equals his best work.

Partial disclosure: you will find, perhaps on the back cover of The Overstory, a quote by me (from my review of his last novel, Orfeo) asserting that Powers is one of America’s greatest living novelists. I explain that claim in the review; to save space here, this is the link: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/review/orfeo.

Further disclosure: I have conversed with Powers several times when he visited the university where I used to teach, and I have occasionally corresponded with him about his books. More disclosure: I have read all eleven of his previous novels, but I review only those that I think are his most interesting and instructive. Penultimate disclosure: since reading in 1973 Gravity’s Rainbow, the deepest drilling environmental fiction of the last 50 years, I value most those novels that tell overstories, what I call “systems novels,” books such as Powers’ The Gold Bug Variations, Gain, and The Echo Maker, which won the National Book Award in 2006. If you share my values, I think you will find The Overstory a profound and important book, one that does for the life that hovers over us what Pynchon did for the fossils beneath us. Even if you don’t now share my aesthetic priorities, you may after reading The Overstory.

As usual, Powers chooses limited omniscience, expanded at times into full omniscience about the futures of his characters. On several occasions in The Overstory, Powers — not one of his characters — directly remarks about art. In the following passage, he seems to address those critics I mentioned by defending the kind of fiction in which the passage is found:

Every one [of the novels his character is hearing read to him] imagines that fear and anger, violence and desire, rage laced with the surprise capacity to forgive — character — is all that matters in the end. It’s a child’s creed, of course, just one small step up from the belief that the Creator of the Universe would care to dole out sentences like a judge in federal court . . . life is mobilized on a vastly larger scale, and the world is failing precisely because no novel can make the contest for the world seem as compelling as the struggles between a few lost people.

Mobilizing fiction on a “larger scale” requires one of Powers’s favorite words, in this novel as well as in the rest of his work: ingenuity. A former computer programmer and musician and student of genetics, Powers knows the importance of form in the communication of information. Probably his most formally ingenious novel is The Gold Bug Variations, with its double structure from four-part genetics and Bach’s Goldberg Variations. In the first short section of The Overstory, a character looks up into a tree described as “fractal.” As James Gleick pointed out decades ago in Chaos, tree branches create a non-linear pattern of fractal self-similarity, both to the tree as a whole and to other branches. The Overstory has a fractal design. The names of the novel’s four parts — “Roots,” “Trunk,” “Crown,” and “Seeds” — indicate the book’s basic structure and growth. Powers’ fractal ingenuity manifests itself in the similarities, bifurcations, branchings, connections, and further branchings among the nine major characters introduced in the independent, named sections of the 152-page “Roots.”

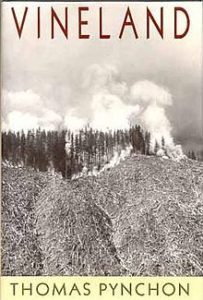

Though the settings from which the characters come are specific and identifiable, Powers supplies few temporal markers, perhaps appropriate for “understories,” a word he uses throughout. Most characters seem to have been born in the late 1950s or early 1960s. The exception is Patricia Westerford, a botanist, author of The Secret Forest, opponent of clear cutting, and Powers’s spokesperson, who is about twenty years older than the others. She has the initials of Peter Wohlleben, who published a popular book entitled The Hidden Life of Trees. If you would like to dig into other roots of The Overstory, there are Donald Peattie’s Natural History of North American Trees, to which Powers refers in the novel; James Lovelock’s Gaia, which furnishes an epigraph; and Thoreau, who supplies several quotes. For those interested in the history of American deforestation, see Annie Proulx’s 2016 novel Barkskins. And for a powerful visual of clear cutting, there is the paperback cover of Pynchon’s Vineland, a novel, like The Overstory, that refers to fractal patterns and is partially set in redwood country:

Some trees grow very slowly. Readers will need to be patient as Powers introduces his people who are similar in their experience of trauma and in their association with trees. Nicholas Hoel grew up on an Iowa farm with one of a few surviving chestnut trees; as an adult he finds his whole family asphyxiated by a faulty gas heater. Mimi Ma’s Chinese father planted a mulberry in the family’s yard in Illinois and years later killed himself underneath it. The novel’s psychologist, Adam Appich, identifies with a maple after his sister disappears on a Florida vacation. Vietnam vet Douglas Pavlicek is saved by a banyan after parachuting into the jungle. Neelay Mehta, son of Indian immigrants in Silicon Valley, falls out of an oak, cripples himself, and becomes a whiz inventor of computer games. Ray Brinkman and Dorothy Cazaly, a married couple, come to appreciate their backyard trees after Ray suffers a debilitating stroke. College student Olivia Vandergriff begins to care for trees only after she almost dies from an accidental electrocution.

Given the commonalities in “Roots,” readers may feel Powers is more an overlord manipulating his characters than a teller of understories. But in “Trunk” we soon see how the characters’ similar backgrounds bring them together. Olivia and Nicholas meet cute over “Free Tree Art,” move together to the West Coast in search of some post-traumatic purpose, join a nature “Defense Force” (that resembles Earth First!), and spend a year sitting on a platform in a giant redwood. Mimi and Douglas meet after a small park in their city is destroyed and join the same defense group in Oregon, where Adam Appich shows up to interview activists for his Ph.D. dissertation on group psychology. After the leader of the group is killed, Douglas is abused by the police in a demonstration, and Mimi is wounded in another demonstration, the two couples and Adam form a Monkey Wrench gang of arsonists. When the action they say will be their last — burning a resort in progress in Idaho — goes awry, one of the gang dies at the scene and the survivors disperse, ending “Trunk.”

A novelist who writes with soteriological intent, Powers is insightful about the motives of his eco-terrorists, their appreciation of natural life after personal traumas, their hatred of industry and police, their idealistic desire to save other humans from their suicidal destruction of forests. Powers spends many pages describing the lives of Olivia and Nicholas 200 feet over the ground in their redwood. Powers’s presentation of this literal overstory — the weather that moves through it, the life forms that exist in it, the close seeing and clear thinking that can occur when one is unplugged in it — is the scientific and emotional center of his book and a mini Walden, for Powers’s language, like Thoreau’s, is equal to what Thoreau called the “extravagant” nature he witnessed by separating himself from humans. Olivia and Nicholas and readers learn to love the tree and its connections to the forest around; when the tree is cut down, the characters’ love turns to rage against the machine of development.

These five activists never meet Patricia Westerford, but several do read her Secret Forest from which Powers periodically inserts the science that underlies The Overstory. As a graduate student, Westerford discovered that trees in forests communicate in subtle ways with each other, warning of dangers, activating defenses, even attacking threats. But she was mocked by other botanists who defended clear cutting and organized replanting of trees — which destroyed the complex ecology of true forests, turning them into monoculture tree farms. When others’ research proves Westerford right, she becomes a well-known authority. Her lecture to environmentalists near the end of the novel is a remarkable tour de force. Like the intricate genetics in The Gold Bug Variations, Westerford’s descriptions of exceedingly complex feedback loops and strange, mysterious tree forms are necessary to substantiate Powers’s stories. The difference is that Westerford’s trees can be seen: just do a Google images search and view the trees for yourself. One of Powers’s familiar prodigies of learning, Westerford is also the conduit though which the author pipes in world-wide myths about forests and trees, such as Yggdrasil and other Trees of Life.

The other important character who does not meet the activists is Neelay Mehta, the game programmer. If Westerford is Powers’s earth-hugging authority on the past lives of trees, Neelay is the high-flying collector of future arboreal information whose last name suggests a “meta” dimension. He turns from producing successful competitive computer games to creating virtual experiences dense with nature, employing hundreds of programmers to make his simulations as robust and rich as possible. At the end of Powers’ novel Gain, a woman dies of cancer probably produced by environmental toxins, but Powers offers a shard of hope by making one of her children a cancer researcher. At the end of The Overstory, Powers moves beyond Neelay’s initial earth-from-above simulations to posit what Powers calls “the learners,” who are like angels of Big Data moving through the air over us, their algorithms assembling and organizing such comprehensive and persuasive information about trees and the rest of nature that humans of the future will no longer need stories to save themselves from suicide. One present function of the “learners” (which Powers doesn’t mention) is identifying from satellites illegal logging operations and sales.

“Crown” and “Seeds” quick cut among the characters’ lives twenty years and more after the arson in 1979. The activists have gone underground, changed names and occupations. Betrayal, guilt, imprisonment, hopelessness, and a possible pedagogical suicide make for a pessimistic crown. Nicholas creates art out of fallen branches that only the “learners” will see. Ray Brinkman and Dorothy Czaly let their backyard revert to woods, but this non-cultivation of their garden, like Nicholas’s art, is an isolated seed. Presumably writing most of this novel before the election of Donald Trump — and the appointment of Zinke at Interior, Pruitt at the E.P.A., and Perry at Energy — Powers seems to have foreseen the current accelerated assault on nature: “Everything’s dying a gold-plated death.” Westerford has written The New Metamorphosis and created a seed bank of endangered species, but only the “learners” offer hope for a transformed future in the real world. Powers has plucked from present streams of data sufficient information to demonstrate the complex lives of trees and the necessity of preserving those lives. He has worked his learning into and through many affecting stories in The Overstory, but he chose to invent environmental activists who failed, who killed one of their own almost forty years ago.

If the “learners” don’t deliver their saving overstory soon, we are going to need “imaginers” more radical — a word with its origin in “roots” — than the characters in The Overstory. Despite the disappointing election results for Jill Stein and the Green Party in 2016, eco-activism — or even eco-terrorism — may not be as futile as the recent history in Powers’s novel seems to imply. Westerford shows that forests migrate as a response to threatening conditions. Ray Brinkman gets interested in trees by playing one that moves in Macbeth. Imagine a hundred thousand humans dressed as trees and migrated to Washington. This would be an event the “learners” and maybe politicians would register. How about a “War on Christmas (Trees)”? Fleet-footed activists come out at night and spray the trees for sale on city streets with orange paint, recalling Agent Orange and disrupting wasteful tree farms. The Kochs’ estates have trees. Could they be girdled by laser-equipped drones? Eco-suicide is also mass murder. Ray Brinkman — a man on the brink — is a lawyer who argues that if the planet is our home, humans have the right to defend it. Florida has a “hold your ground” law. Imagine protesters breaching the fences at Mar-a- Lago and taking back our home. Twenty years ago, I published a novel (Passing Off) in which an eco-terrorist intends to bring down the Parthenon, which she considers a symbol of building mania in a city surrounded by deforested mountains. A scholar has recently claimed that a scene on the Parthenon frieze approvingly depicts human sacrifice. I have begun to wonder if only the sacrifice of human lives can slow down, if not prevent, environmental catastrophe in the future.

Final disclosure: like Pynchon’s Tyrone Slothrop, I have a family history of cutting forests. My grandfather ran a sawmill in the Green Mountain state. An uncle cut trees. As a teenager, I peeled pulp and stacked lumber. But I don’t think my guilt affects my judgment of the importance of The Overstory. Read the e-book version of this 500-page novel, save a tree, spread Powers’s words, become a seed of information, contribute to the “learners’” global truth, and think about performing some arboreal action for the sake of your grandchildren.

Tom LeClair is the author of three critical books, six novels, and hundreds of reviews and essays in national periodicals.

This post may contain affiliate links.