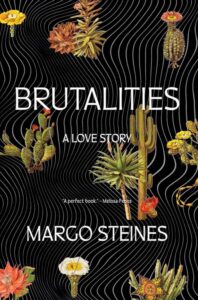

[W.W. Norton; 2023]

“I am thirty-seven, pregnant, in love, and effectively locked in my apartment,” writes Margo Steines on the first page of her memoir. Brutalities: A Love Story opens in a liminal space: Steines is nearing her third trimester while quarantining in Tucson during the spring of 2020, surrounded by the fresh calamity of the pandemic. The first chapter establishes Steines as a protagonist with relatable desires and longings. She feels safe at home with her partner, “N: . . . the person I spent so many years of my life stumbling around looking for.” They share a bowl of berries; she marvels at the gentleness that suffuses her life. The scene is a study in tranquility. Each successive chapter alternates focus between Steines’s unfolding pregnancy and the many forms of violence that saturate the book.

The second chapter opens with pain: “the first pain [Steines] paid cash for.” The reader experiences immediate tonal whiplash, as Steines cuts from the serenity of her present to the brutality of her past. First a full back tattoo, then the time she “paid a woman to strap me to a leather cot and hit me with a stick,” followed by Steines’s former employment, when she “was paid many thousands of dollars to hit men with similar sticks.” The plainness of her language grates against the sensationalism of the content. Like a wound-up trebuchet, the narrative is propelled by tension. The other man who shadows the book, Dean, N’s foil, is introduced as the owner of a compromised forklift that he “used . . to dangle girls like [Steines], girls who felt lucky to be there.” The narrative bite of Brutalities is generated by this juxtaposition: the magnetic charge between Steines’s longing for gentleness and her attraction to violence.

“My desire for tenderness was a poorly kept secret,” Steines says. This revelation emerges from an isolated farm where she lived with Dean, a setting she returns to throughout the book. Surrounded by broken dishes and animal bloodstains, Steines dreamed of an alternative future: “me pregnant, him kind, both of us utterly changed.” The reader already knows that Steines will arrive at this longed-for future, though partnered to a very different man from Dean. But there is a desert of suffering to cross first.

Steines’s project is to examine her complicity in her own suffering, and by doing so, to develop a more transparent relationship with her desires. In certain ways, Steines’s narrative follows what Parul Sehgal, in her landmark New Yorker essay, codifies as “the trauma plot.” “Unlike the marriage plot,” Sehgal writes, “the trauma plot does not direct our curiosity toward the future (Will they or won’t they?) but back into the past (What happened to her?).” The contemporary timeline holds minimal surprise: Steines is pregnant at the beginning of the book; at the end, she gives birth. The story’s intrigue lies in the interim: how (and why) Steines progressed from teenage domme to would-be homesteader to unionized metalworker to writer to mother-to-be.

The story develops through a web of associations, which allows Steines a chronological freedom to skip through exposition and alight where relevant. The book’s chapters rarely tell a single story from beginning to end. They function more as thematic meditations, circling around questions of agency, conflicting desires, self-sabotage, and the limitations of the body. She lurches into an episode and then leaves it hanging, the way she used to dangle from Dean’s forklift, “up off the ground with rope.” However, this suspension isn’t bothersome. Rather than backstory being scattered throughout, it’s strategically deployed for thematic relevance and narrative effect. The complex timeline reads organically, a testament to Steines’s skillful narrative composition.

In a fuller sense, Brutalities defies the narrow script—what Sehgal calls “the coercive tidiness”—of the trauma plot. Steines’s memoir falls into the category of “stories [that] rebel against the constriction of the trauma plot with skepticism, comedy, critique, fantasy, and a prickly awareness of the genre and audience expectations.”

Steines rejects the trauma plot paradigm that would interpret her attraction to violence as a reprocessed aberration from earlier in life—essentially, that would reduce her actions to symptoms. She repeatedly frames her involvement with violence as something she chose, however misguided or uninformed her choices. “The stories you’ve heard about trauma and violence are reductive,” Steines states. Within the trauma plot, suffering is placed onto the protagonist by an external bad actor, be they abusive parent, nefarious stranger, or systemic force. The traumatized protagonist is characterized by passivity. Sehgal points out that when Virginia Woolf wrote about her childhood sexual abuse, “she settled on a wary description of herself as ‘the person to whom things happen.’” However, Steines refuses to absolve herself. She acknowledges the inadvisability of her choices and emphasizes the aimlessness of her younger self while taking responsibility for her role. “Violence . . . wasn’t given to me,” she insists. “I set out to find it.”

The origin of her compulsions holds little interest for Steines. The trauma plot often revolves around identifying an initial traumatic occurrence which sets the tragic trajectory in motion. Steines’s personal history is speckled with countless potentially qualifying incidents, but she refuses to pinpoint an inciting event. She regards “the hurricane of [her] selfhood” as something innate, having emerged so early it was either congenital or inevitable. She reiterates the lack of utility she found in therapy. Identifying the origin of her issues, however useful in placing blame, proved irrelevant to Steines’s more pragmatic ambitions. “Along the way I lost the conviction that uncovering the whys of my ways was a worthwhile enterprise.” She lists a string of underwhelming insights gleaned from hours with therapists: “I was sensitive, and I grew up with anger in my home”—who wasn’t; who hasn’t?—“and I felt uncomfortable, and I sought comfort.” But Steines immediately interrogates the dubious emotional arithmetic that would determine her path from such generic inputs: “Is that all it took for my dominoes to tip?”

Rather than focusing on a single negative experience, Steines turns inward: She examines the many ways that she collaborated with her own destruction. Her quest for pain, centered on the intersection of violence and sexuality, emerged from a burning desire for “something fierce enough to puncture the suffocating cocoon of numbness [she] lived inside.” The memoir’s arc lies in Steines’s progress toward conscious agency. While she refuses the victimization implied by the trauma plot, Steines’s depiction of her earlier self is marked by ambivalence. “My job at the dungeon,” she explains, “was a consequence of the same numb zeal that made me say yes to everything: any pill or powder, any new way to touch or be touched. Nothing felt like much of anything, so I kept looking for whatever was more intense, more extreme.” Steines was formless, easily shaped by stronger wills. About Dean, she writes, “we fit easily, because he was a solid object and I was water and there was nothing I could not shape myself around.”

Structurally, her separation from Dean is the climax of the book. His departure is the Jenga tile that topples Steines’s entire tower of destructive coping mechanisms, and over time, she identifies safer containers for her curiosity. Age and maturity quench Steines’s thirst for danger and damage, but violence itself retains its magnetic pull. “I was transfixed by violence and power, and maybe I still am,” she acknowledges. “But my relationship to violence and my desire to be hurt have been altered over time, and today I no longer need or wish to be the object upon which violence is exerted.” Her insatiable craving for pain dims as she cultivates a pleasure in tenderness.

Brutalities is not a triumphant recovery memoir. To whatever extent “healing” happens, it occurs off the page. Steines refuses to characterize her past self as fallen, foolish, and wicked, while presenting her contemporary one as whole, understanding, and redeemed. She never apologizes for her attraction to violence, never castigates herself for what she’s drawn to, but she openly grapples with the implications of her choices.

Within the typical contours of the trauma plot, the violence that Steines experienced and participated in would be characterized as wholly undesirable, the chemical residue of early abuse. Recovery from trauma would mean rejecting rough touch wholesale. “If we say gentle touch is the only ethical touch, that is a clear and easy boundary to abide by,” Steines acknowledges. But she uses her story to create a space for nuance and greater complexity: “That boundary also elides the lived experience of a lot of people, including myself, who are drawn to roughness in its various forms and who seek outlets for those urges.”

Her previous experience allows her to interrogate what she gained and continues to gain from exposure to physical power. “What does it mean,” she asks openly, “that now, deep into my thirties . . . I am no longer interested in getting hit but I am still circling violence, ever finding new ways back to it?”

This reflective capacity is what separates thirty-seven-year-old Steines from her many previous iterations. She is still desirous and intense, but she evaluates her choices rather than being driven by them. She has come to trust her capability to self-regulate, maturing into the dungeon master of her own life.

Steines doesn’t limit her investigation to the circumference of her own experience. “In deft hands,” Sehgal says, “the trauma plot is taken only as a beginning . . . With a wider aperture, we move out of the therapeutic register and into a generational, social, and political one.” This is what Steines gives the reader: a consideration of violence as a form of truth. She identifies the contradiction of refusing to acknowledge violence while participating in a society fueled by it. In “Sick Gains (II),” she calls out some of society’s more accepted forms of violence: institutionalization, excessive pharmaceutical intervention, and the minimization and disregard so many people, particularly women, receive when seeking healthcare. Street harassment, workplace misogyny, the criminalization of sex work, and police violence all appear in the text as extensions of Steines’s inquiry into violence, power, and agency.

The inability to acknowledge or abide violence isn’t purity, Steines insists, but dishonesty. “We lack hunger for truths about the violence we participate in,” Steines states. She relentlessly investigates the confluence of power, desire, and true sensation. From the dungeon to the MMA ring, Steines observes how rough touch can, in the proper context, create space for authenticity and tenderness. Brutalities: A Love Story is a breathtaking work of memoir that reveals the startling power of gentleness.

McKenzie Watson-Fore is a critic and writer based in her hometown of Boulder, Colorado. She holds an MFA in Nonfiction from Pacific University. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in New Critique, Colorado Review online, CALYX, and elsewhere. She can be found at MWatsonFore.com, drinking tea on her back porch, or dancing Argentine tango.

This post may contain affiliate links.