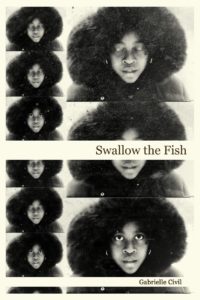

[Civil Coping Mechanisms; 2017]

[Civil Coping Mechanisms; 2017]

So You Want to Be a Wizard. Out of Sight, Out of Order. In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. Maud Martha. Maker of Saints. Dictee. These are some of the books mentioned and/or discussed by performance artist Gabrielle Civil in her introduction to Swallow the Fish. Slyly titled “Prefaces,” this introduction names the faces preceding her own, as she sews her body and concerns into a continuum of feminist art and thought. Her choice to pluralize creates an electric textual encounter: a stodgy, overly familiar term is torqued into mysterious forces, a portal arriving out of what previously seemed impenetrable. “The aim of her work is to open up space.” This line appears on her website in bold letters sprouting from the right hand corner of a photo. The image documents Civil lost in motion: legs apart, torso bent, arms and face a storm of red-washed hurricane swirls. Her body is rooted but also fluid, suffusing and evaporating, caught in a process of transfiguration. So You Want to Be a . . . . To make a book that instructs and alchemizes, a book of witnessing and archives. You want to be an experimental body artist. What steps to take? How to become? Why?

Swallow the Fish presents itself as “a memoir in performance art.” Through intimate vignettes, Civil traces and retraces her own conscious-waking into a life of words, creativity, and art. Born in Detroit to a middle class diasporic family (her mother is African-American and her father is Haitian), Civil sketches a portrait of a precocious overachiever with a passion for books, languages, and intellectual pursuits. Eventually her love of poetry expands into an interest in “sowing and spreading seeds of language” into public space. Inspired by the poetical explorations she undertook with No.1 Gold Collective, a collaborative conceptual art group Civil co-founded as an NYU grad student, her poems begin to take on a new materiality, bursting from the page in order to fuse, to circulate, to confront. In an interview with Book Nook, Civil explains how vital presence and mindfulness are to performance art, both for the artist and audience. Performance offers an opportunity to be fully present with one another, to be attentive with all the senses and then some. “To arrive,” as Civil says. She returns to this idea of circulation, to this thrilling preoccupation/provocation: how to disseminate poetry out in the world via alternative means, how to remember that body moves language.

The book collects together essays, ruminations, performance texts/notes/ephemera, anecdotes, correspondences, lists and more. Inside we find an erotic collision of typography, image, word, approaches.. This is a text performing itself and the limits of its form. Throughout we stay attuned to the desires and doubts of a self-described black feminist artist, carving and tending her path despite the push back, condescension, (white) shock upon seeing (someone like) her present and participate at radical, avant-garde, and/or academic spaces. As if she is an anomaly and/or intruder.

He said: what happened here? You’ve said something in another language that I don’t understand. He said: I’ve looked at all of this — the paper, the windows, the frames, the ladder, your words, your body, the charcoal, the fire — and I can feel you’re speaking but I can’t understand what you’re saying.

“On Interpretation” details an incident where a white man approached Civil right after her performance of “infestation of gnats,” which was written in response to the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan. He wanted Civil to explain what he had experienced. She was flushed in the aftermath, unable to give this man concrete answers. Later she dwells upon and agonizes over her neutral response. Was she a coward? Inattentive? Justified? Her rumination becomes a ping-pong-play between two voices, a chance to associatively dip into the private moments, revelations, and coincidences that fed into “infestation of gnats.” All of that she channeled into this language of flesh, paper, charcoal, fire. How to pinpoint these encounters into a palatable explanation?

What is the critical apparatus to engage a performance art work, a work that started as poetry on a page and moved into theater, a piece that happened only three times many years ago and has never happened since?

What did it mean then?

What can it mean now and how?

How has the meaning changed over time?

Then and now. Civil makes a home in the uncategorizable, in the remains of lived experience. In the interplay between text, image, and body she knits together questions surrounding scholarship, the transitional, memory, and the ebb and flow of interpretation. Is the point to seize meaning or to engage with it through growth, failure, rearrangement? Swallow the Fish is an act of returning, re-presenting, a sensuous gaze concurrently looking backwards, forwards and slant. Civil’s interest in performance art partly emerges out of an impulse to dissolve gender, racial, and sexual barriers. A place to uncover deeply embedded societal scripts, the space of the performance becomes a method of thinking through, where one can correspond intimately with fears, stirrings, aftermaths, each other. Marina Abramović, Sophie Calle, Karen Finley and their nasty brazenness. How they veer off track with gleeful abandon. Civil recalls seeing Finley strip to her underwear and step in a water-filled basin before peeing into a bucket. The effect of her gesture is an exhilarating slap to the face. At the same time, Civil cannot help but wonder “who got to do those things? Who got to be the performance artist? Which people in which bodies?”

Another memory: Civil is the lone black women at The Walker Art Center, there to see an installation/performance by Aaron Young. It involves white walls, high ceilings, wine, colored sunglasses, empty space, a helicopter. She converses with two women: what is the intention of this piece? They all feel uneasy. One woman — young, blonde, willowy — expresses her frustration by taking off all her clothes and lying in the middle of the floor. Eventually the gallery owner quietly tells her to put her clothes back on as the artist is afraid “[she is] stealing his thunder.” This moment brings up two points for Civil. One, if you create a space and invite “people to do whatever,” you must be prepared to engage with this bringing together and improvisation of bodies. Second, what would have happened if Civil took off all her clothes and claimed the gallery floor? She imagines herself bending down to untie her boots and the gallery owner running breathless to say No. Sorry. “We don’t do that here.” Would he have whispered in her ear like he did Karin? Perhaps he would have mistaken her for a hip hop video vixen, the angry black woman, “uncivilized.” This episode opens up the sense of surveillance and containment attending life as a black woman: how your movements are scrutinized, minimized, distorted; how this erasure has origins in long-echoing pasts. Then and now. What has changed?

An intervention into the academic lecture/artist talk, “Displays (after Venus)” was performed for faculty during a visit to Mount Holyoke College. Signaled by the call “Step Right Up,” Civil undressed to her bra and underwear and stood on a table. Every so often the only white man in the room yelled “Turn!”, to which she shifted into a pose while definitions of “display” projected onto the wall. After doing this four times, she stepped down from the table, put her clothes back on, and began a slideshow that started with an image of Saartjie Baartman. Afterwards, an older black student revealed the performance made her think of her own body and the shame she would feel. Civil’s scholar friend, a light-skinned biracial woman, explained being afraid for her, for the violent reactions her performances could elicit. “Displays (after Venus)” finds Civil grappling with legacies of exploitation and fetishization. Because her body did not fit the narrowly-constructed “ideals” of womanhood (i.e. white, thin and unassuming), Baartman was exhibited as sideshow entertainment throughout 19th-century Europe under the name “The Venus Hottentot.” Her narrative haunts Civil:

As a black woman performance artist who necessarily has had to come to terms with the spectacle of my own black body: I wonder: What kind of authority did she have over her body? How did she move? What made Saartjie Baartman decide to come to Europe in the first place? Did she feel shame? Did she feel resignation? What were the parameters of her agency over her body, over her life? In the 26 years that she lived in Europe, was there no way that she could do back home? How did she tell the story of what was happening in her life? Did she see herself as a freak, as a captive, or as some kind of “performance artist?” Was she somehow assimilated into her role as Other? Did she merely lack any other options? And to what extent was she—or are any of us—complicit in our own exploitation?

By threading performance to the experience of Baartman, Civil upends our assumptions around artistic displays of the body, demands we consider the fact that performance art engages with unruly ghosts and wounded riddles. She wonders what her grandmother would think if she saw her on the verge of baring all. “[H]ow could you let yourself be seen?” Unavoidable, the suffocating burden of modesty-disguising-shame assembles an environment wherein the body cannot be trusted. Must be policed. As a black woman you move hounded by dangerous projections. You are a language one is trained to misunderstand. Civil’s body-poetries recognize and engage with these knotty intersections of personal, historical, and creative realities. “Traces of [her] body” transform to written word before resuscitating into a spectacle of sensations, living tableaux offering chances to expose and reclaim. Out of Order, Out of Sight. Adrian Piper’s collection of writing “beckon[ed]” Civil to break the system, to agitate, to risk. The title is “a warning and an exaltation.” To commit to being out of order as a woman of color, is to chance being placed out of sight: “invisible, overlooked, hidden away.”

One more encounter: a performance of “art training letter (love)” finds Civil in ritualistic fervor: preparing, perturbing, cleaning up, failing, trying again. As her body interacts with honey and other props, a recording of a letter she wrote to her friend/collaborator Madhu plays. The letter details Civil’s sexual encounter with a Moroccan man weeks after 9/11. Moments of vulnerability, permeability, and pleasure suddenly shift into a meditation on bombings, terror, uncertainty. Civil performs this for an event organized to denounce the U.S. government’s aggressive response following the attacks. The audience dismisses her piece as narcissistic, inappropriate, indulgent. How uneasy they are with the blending of personal and political, private and public, eroticism and catastrophe. Some (most?) of their alarm stems from who is telling this story, whose body is revealed as desirable, empathetic, unpredictable.

Swallow the Fish continues and builds upon the interventions of artists like Piper, Ana Mendieta, Yoko Ono, Coco Fusco and countless other women named and forgotten. Civil is generous with her inspirations and guardians, giving equal space to the preceding and contemporary voices in conversation with her own process. Never does she claim to exist in a vacuum — her work unnerves in its willingness to contact over and again. Though she candidly acknowledges the loneliness and alienation one can feel as a woman of color committed to creatively dismantling oppressive narratives, Civil situates herself amongst of bubbling sea of feminist black voices, reminders of the enormous well of defiant poetical gestures, others to learn from and with.

Breaking taboos. Dancing the fine line between crazy and brilliant. Feeling something alien and alive more from transparency into your body, fish, rippling wound or wound.

The last phrase samples a line from “Dusting” by Rita Dove: “the clear bowl with one bright / fish, rippling / wound!” To swallow the fish is to step into liminal, irrational realms. A dare, an invitation, a puzzle, a ceremony. To swallow the fish is to commune with bodily and unheard languages. To manifest your presence into poetry, careful not to rush or run away. Will you swallow the fish?

Read an excerpt of Swallow the Fish on Full Stop here.

Allison Noelle Conner lives in Los Angeles, where she works as an assistant fiction editor for The Offing.

This post may contain affiliate links.