[University of Minnesota Press; 2016]

[University of Minnesota Press; 2016]

Tr. by Jo Levy

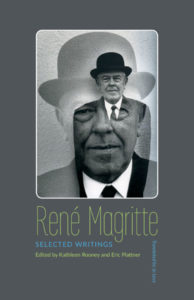

The Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte (1898 – 1967) might not have enjoyed the rock star fame and longevity of near contemporaries like Salvador Dalí or Pablo Picasso — or served as the complete game changer that was his impressionist hero, Édouard Manet — but for what he did achieve on his canvases, Magritte had the exceeding power of knowing exactly what he was doing and putting it into precise words. Language, in fact, is a primary element in several of his best-known paintings, and a subject they contemplate. His life’s work positioned Magritte as a poet of images, a collagist of familiar objects repurposed to create visual metaphors that literary surrealists, the followers of Stéphane Mallarmé, eagerly took up. What isn’t known by the average English-speaking museum goer is that while André Breton might be the most visible surrealist scribe, Magritte, too, generated a significant number of short manifestos and experimental prose pieces. He also frequently made himself available for interviews throughout his career, as paintings that were once sold in the 1920s for a thousand francs were sold again in the ‘50s and ‘60s for millions. Eleven years after the painter’s death, his complete writings were published in French. However, an English-translated selection of these pieces and interviews has been absent from the record until now.

In her introduction to this new Selected Writings, editor Kathleen Rooney tells of her discovery at the 2014 Art Institute of Chicago exhibit, The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938, where many of Magritte’s paintings were accompanied by quotes from the artist’s writings. With the help of an intermediary, Rooney uncovered a project begun in the ‘80s by the late British translator Jo Levy to translate Magritte’s entire writings, which take up over 700 pages in the French edition. After comparing the French Collected writings and the selection that Levy managed to translate before his death, Rooney found a “judicious” reasoning behind Levy’s selections, omitting redundancies and ephemera. In some cases, Rooney, along with her colleague and editor Eric Plattner, decided to commission new translations to make this first English edition of Magritte’s writings definitive without being repetitive.

Was Magritte a surrealist? One of the shiniest lures drawing today’s reader to the musings of an exemplar of a concluded art movement is to see how such an icon wriggles and detaches himself from periodization, the hook of history. Just as, in Magritte’s The Betrayal of Images/La trahison des images, the painting of the pipe captioned “this is not a pipe,” the artist confronts the incommensurability between the substance of a thing and its label, so also the substance of a painter evades labeling. And yet, paging through the work online or in glossy volumes, through all the trompe l’oeil framed skies and curtained landscapes, the severed hands and birdcages, bedpost pillars sprouting from rocky seaside cliffs, female nudes contorted into bathroom plumbing, I see nothing that didn’t once aspire to stir up and transcend its moment that didn’t ultimately settle and embody that same moment. Aesthetically, surrealism and Magritte are so intertwined and specific, so dated. Ironically, it is the recurring figure of Magritte’s disposable bourgeois investigator, in period bowler hat and trench coat, that stands as the artist’s most unique and emblematic contrivance.

In a body of work that made every effort to avoid overt symbolism, the bowler-hatted man represented the status quo every surrealist intended to subvert. This didn’t keep bowler-hatted Magritte from purging surrealist conventions from his own repertoire. Magritte’s series of short manifestoes from 1946, “Surrealism in the Sunshine,” takes clear-eyed account of visual and literary techniques from the preceding half-century, freeing this impulsive movement from the rule of the unconscious and leading it into a more open space of intention. “Automatism . . . is no longer of value today: it is extremely useful in psychoanalysis, as is the use of the microscope in biology,” he announces. “Investigations into the unconscious . . . are of no interest to us except as a means to action, the truth being of no importance to us,” he adds. Truth, like beauty, fell back on the eye of the beholder, which habitually mistook truth for likeness. Surrealists pledged to avoid painting faithful likenesses in the manner of their Impressionist forebears, but Magritte saw no big advance in denying the viewer natural effects of sunshine on whatever misshapen freak object appearing in his frame.

Magritte did, however, caution against overvaluing any talent or “artist’s skill” a painter displayed. In this way, he voided the preceding realistic achievements of neoclassicism as well as the abstract fetish of materials and color that rose after surrealism’s heyday. Refusing to flee from reality, he instead took up the intellectual challenge to interrogate the latent mystery in his environment. This motivation distanced him from the act of painting toward the conceptual arraignment of painted objects, which is why even though some of his distorted figures resemble those by Dalí, and some of the cruel acts committed in his scenes recall Balthus, Magritte’s career presents a wider-reaching institutional philosophy. Beyond a nostalgia for European painting between and immediately following the two wars, Magritte’s paintings defy time by evoking contemporary art spaces sprung up in the decades following his death. His scenes are staged spectacles in galleries, his landscapes found on surrounding museum properties.

The seed of this conceptualism, thinking over painting, is evident from the ‘20s onward. In the first piece in Selected Writings, “Pure Art,” Magritte is already inveighing against virtuosity — it’s “for idiots.” The artist who treats the subject being painted as the goal of the work “proves that he is not conscious of the reactions influencing him.” He is not a master but a slave, a decorator. Later autobiographical essays and interviews return to the frustrations the young Magritte experienced as an art school dropout and a designer at a wallpaper factory, as well as an advertising illustrator. These somewhat brief commercial activities no doubt informed Magritte of what he termed, in “Bourgeois Art,” from 1939, “capitalist hypocrisy.” Bourgeois individualism, which isolates people through competition, is contrasted here with the revolutionary artist, “who has inherited a mass of habits and confused feelings.” Such an artist is distrusted and led astray by contradictory norms.

Above all, Magritte declares in one interview, he is not a sociologist. In another, from 1962, he cops to sharing the artistic concerns of surrealists, and in fact contributing to the movement’s development. He defines a surrealist as a conscious artist: “The artist in general is only conscious of his art, which is very different from a Surrealist who uses art. Art is not the Surrealist’s raison d’etre; if he uses it, it’s as a means of thinking.” To the aesthete who insists on allowing a single work to speak for itself, Magritte is thinking ahead of you.

Christopher Wood is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, who now lives on Long Island.

This post may contain affiliate links.