This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

It is always the right time for surrealism—flexible, various, and mobile—and for surrealists, each an energetic, dubious coil that can be unpacked from a suitcase to set the city alight or else, when arranged in fractious formation, in dive bar, asylum, or anthology, re-start the universe with a klatschy, clashy bang. Barely a hundred years since its inception, surrealism’s signature energy may be detected across the planet: lively, dissatisfied, disruptive, and, crucially, plural. André Breton famously stipulated that Beauty be convulsive; and with the entire planetary climate, global politics, techno-capitalism, and literary institutions in states of havoc and convulsion, it is fitting that the last few years have brought an extraordinary—and extraordinarily diverse—array of surrealism(s) bounding into view.

This salubriously dubious bounty includes new translations or re-releases of books by historical Surrealists, works of exuberance and strangeness born on currents of exile and upheaval: a devout, lovely volume of Robert Desnos, translated by Lewis Warsh (Winter Editions); deft and drastic tales by Argentinian Sylvia Ocampo translated by Suzanne Jill, Katie Lateef-Jan, and Jessica Powell (New York Review Books); hyper-vivid, alarming stories by Anglo-Mexican poet Leonora Carrington (Dorothy Project), to name a few. These form a siren-chorus with new translations of latter-day surrealists: the late Moroccan poet Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine in translation by Jake Syersak and Connor Bracken (Oomph!, Diálogos, Cleveland State); the visionary Kim Hyesoon translated by Don Mee Choi in her major mode and by Jack Jung when publishing under her alter-ego, N’t; femme subversives like Olga Ravn and Yoko Tawada, translated by Martin Aitken and Susan Bernofsky, respectively; and the robustly queer Mexican poet Luis Felipe Fabre, translated by JD Pluecker and Heather Cleary, whose works unfurl a peacock’s tail of gonzo-scholarship. As in the belled security mirrors hung up above the pharmacy, or as with a chorus-line of wigged-out angels exiting heaven, these surrealisms multiply in dazzling, unnerving arrays and waggle at us weird signals.

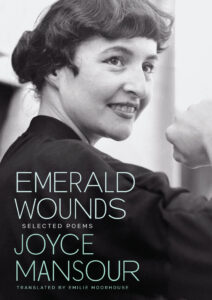

The latest in this starry cavalcade of Surrealists to return to (Anglophone) earth in this late, accursed hour is Syrian-Jewish Anglo-Egyptian poet Joyce Mansour, thanks to the new volume Emerald Wounds: Selected Poems, translated by Emilie Moorhouse, selected and edited by Moorhouse with Garret Caples and published by City Lights. The title Emerald Wounds already spasms with evocative contradiction, inscribing Mansour as the capital-S Surrealist she is. Not only are emeralds and wounds seemingly polar opposites in terms of their positive and negative cultural valences, but also, as jewels, emeralds scatter dazzling light outwards while wounds draw the sick vision perversely in. In this sense, perhaps jewels are literally repulsive, as they repel light beams, while wounds are attractive, as they morbidly absorb the gaze. Closely considered, the poles of attraction and repulsion evoked by this title reverse, forming a voltaic cell of paradox, of the type Surrealism holds to be foundational—”as beautiful as the chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table,” as the catechism of orthodox Surrealism goes.

Mansour was a capital-S surrealist by all other standards, as well. Born in England to affluent Anglo-Egyptian-Jewish parents in 1928, English was her first language, though she returned with her family to Cairo in early childhood. Typical for a member of the twentieth-century avant-garde, mobility and displacement thus defined her youth, as did other sudden reversals of fortune: Her mother died of cancer when Mansour was fifteen, and her first husband, whom Mansour married at eighteen, died just six months after they were wed. Per Moorhouse’s introduction, this double loss undid the young Mansour, who isolated herself and began writing English poems of rage and imprecation. These verses have not survived. Yet Mansour herself retrospectively described this initial period of derangement and poetry with a Surrealist keyword: “It was a kind of revolt.”

By all accounts Mansour’s life stabilized upon marriage to the Francophone Egyptian Samir Mansour, who was also Jewish. The pair moved in extremely elite circles which brought her into contact both with King Farouk and with figures from the Egyptian surrealist movement Art and Liberty. This in turn led to her first volume, Cris (Screams) to be published in Paris in 1953 when the poet was twenty-five. But in 1954, in the aftermath of the Egyptian Revolution, her family’s assets and property were seized and Mansour went into exile in Paris—a reverse exile in the metropole, again typical of Surrealism’s unexpected itineraries. Over the decades, Mansour published sixteen books of poetry, as well as drama and prose, and became a special favorite and friend of Breton’s, seemingly outliving the child-muse role which limited the careers of some Surrealist women. The jacket copy of Emerald Wounds confirms Breton’s exceptional estimation of Mansour: “You know very well, Joyce, that you are for me—and very objectively too—the greatest poet of our time. Surrealist poetry, that’s you.”

If Mansour’s approval by Breton made her an absolute exception among Surrealist women, even more exceptional is the fact that Emerald Wounds entails the second major volume of Mansour’s work available to Anglophone readers. In 2008, Mansour got the full Modernist genius treatment with Essential Poems and Writings of Joyce Mansour, selected and translated by the poet and scholar Serge Gavronsky. This volume ran to 437 pages, was published by the iconic Black Widow press in a series including volumes of Breton, Desnos, Éluard, and Char, and came dressed in the traditional avant-garde war colors, black and red. Mansour is so far the only woman to be featured in this line-up.

It’s surpassingly rare for a woman poet of any period—excluding, perhaps, Sappho—to be the subject of two major translations into English, let alone by translators of such verve, acumen, and commitment. The resulting volumes constitute a supple, necessary dyad. Gavronsky’s Essential makes a comprehensive survey of Mansour’s poetry, prose, and plays in order to establish her firmly and exultantly in the Surreal firmament. His introduction places her at iconic meetings and amid literal group photos of the famous men. More than a matter of apparatus, design, or framing, Gavronsky’s translation is itself Surreal. Of his many excellent assessments of Mansour’s style, he remarks on “that characteristic Surrealist disconnection of one part from another in the same line [that] willfully leads the reader astray and is evident of Joyce Mansour’s verbal jouissance, a voluptuous refusal of sequence.”

Where Gavronsky seeks to be resolutely representative and scholarly, excerpting each volume with separate dated title pages, Emerald Wounds divines another kind of essence from Mansour’s oeuvre. The volume presents a supple selection of poemsunfolding as an unbroken sequence, arranged chronologically, but not demarcated into separate volumes in the body of the text itself (though the table of contents does provide such demarcations). As it proceeds, Emerald Wounds begins to function almost as a single poem, gathering resonance as it deploys a singular, dark-hued oceanic tone, an unwinding skein of erogenic currents, synesthetic and immersive.

The contrast in approaches is evident not just in the macroscopic arrangement of the books but in the selection of the poems and the mood and pacing of individual translations. Take the first poem in Moorhouse’s selection, from the debut collection, Cris:

Je te soulève dans mes bras

Pour la dernière fois.

Je te dépose hâtivement dans ton cercueil bon marché.

Quatre hommes l’épaulent après l’avoir cloué

Sur ton visage défait sur tes membres angoissés.

Ils descendent en jurant les escaliers étroits

Et toi tu bouges dans ton monde étriqué.

Ta tête détachée de ta gorge coupée

C’est le commencement de l’éternité.

This poem starts the volume like a door flung open. The reader, as a passerby, looks upwards at a backlit scene as the coffin-bearers “go down the narrow stairs swearing.” At the absolute top of these stairs is the speaker, who opens the poem: “I lift you in my arms / For the last time.” Moorhouse’s choice of this vignette to initiate Emerald Wounds emphasizes its startling contours, in contrast to Gavronsky’s all-in approach, which crowds the poems of Cris three to a page, blurring the definition of individual verses such as this one. Moreover, in his translation, Gavronsky reverses the opening two lines so as to emphasize somber ceremony rather than speakerly drama: “For the last time / I lift you in my arms.” As the poem continues, so does Moorhouse’s attention to the speaker:

I hastily place you into your cheap coffin.

Four men lift it once they’ve nailed shut the lid

On your undone face on your anguished limbs.

With its second-person possessives, its exasperated tone, and the “Daddy”-like rhythm of that last line recalling lines like “With your Luftwaffe your gobbledeygoo,” the imprint of Plath on Moorhouse’s translation is unmissable. A calm and fatal magic is worked by the last line of her translation—”It is the beginning of eternity.”—recalling the chilly finales of Ariel. By comparison, Gavronsky ends his translation of this verse, “That is the beginning of eternity”—directing the poem back on itself, to find the missing antecedent of that “That.”

Gavronsky’s translations are emphatic, indelible, intensely valuable. Yet in Moorhouse’s versions of these early poems, something more uncanny builds from verse to verse; the curtain swings shut on one poem, but the exhalation it releases will billow the curtain of the next, as enacted by the turn of the page. This requires a nervy steadiness from the translator; in Moorhouse’s hand, we see a sisterly resemblance between the early poems of Mansour and those of other singular twentieth-century women poets, like Argentinian Alejandra Pizarnik and Uruguayan Marosa di Giorgio, whose sequence History of Violets opens, in Jeannine Marie Pitas’s translation, with a cosmic mic-drop mirroring Mansour’s: “I remember eternity.”

In Moorhouse’s handling, the sexual directness of Screams and Shreds (“May my breasts provoke you / I want your rage”) entails a bright-hulled tonal skiff floating on an undertow of erotic textures and urges. This carnal energy is distributed to a Lautreamontian menagerie of octopi, cats, rabbits, ants—a tapestry of creaturely devourment. The paradigmatic site is at once the bed and the beach, where tonal levels can rise and fall, abrade and retreat. If, to paraphrase Stokely Carmichael, the primary position of the female body in orthodox Surrealism is “prone,” here, under Mansour’s explicit direction, speaker and seductee alternate being emptied and filled, charged and depleted:

The tide is rising in the sky reeling with love

Toothless in the forest I wait for my death, silent,

And the tide is rising in my throat where a butterfly dies.

Ultimately, the shreds this second sequence brings to mind are the “marine snow” of decaying biological matter that descends uncannily through oceans—nutritive, serene, ghostly, transformed.

After this early tide of erotic maquettes, the tone of Emerald Wounds shifts and the poems broaden. The poems from Reach and Birds of Prey (1958, 1960) reflect and pointedly deflect the ways in which mid-century mass media addressed and confected the middle-class housewife. With titles like “Advice for Running on Four Wheels,” “Cold Out? A Dress is Essential,” “Practical Advice While You Wait” and “What to Wear This Summer,” the poems open with a glittery brio which again recalls Plath at her most bright and brittle. As with Plath, however, these poems divulge strange warps and intervals where the mannequins are bald and the grin sags. “Dowsing” opens with one such accusing interrogative—”Husband neglecting you?”—and, after some opening witticisms, ends in an absolutely stunning run:

I do not know hell

But my body has been burning ever since I was born

No devil stirs my hate

No satyr pursues me

But the verb turns to vermin between my lips

And my pubis too sensitive to the rain

Motionless like a mollusk flatulent with music

Clings to the telephone

And cries

In spite of myself my carrion fanaticizes over your ousted old cock

That sleeps

These short aggressive phrases create a rocking effect, driven by alliterations in Mansour’s French which Moorhouse carries agilely into the English: verb/vermin, motionless/mollusk/music. The poem flares into a long masturbatory line in which “fantasizes” grows an extra syllable, “fanaticizes,” before collapsing into an exhaustion evoking less relief than a pause between bouts.

After this hectic middle hinge, the final movement of Emerald Wounds showcases Mansour in the fullness and maturity of her powers, including the magnificent Carré Blanc (White Square,1965), and the entirety of the 1986 Black Holes, which appears in Moorhouse’s deft curation as the summit and summation of Mansour’s oeuvre (an effect blunted in the encyclopedic variousness of Gavronsky’s volume). In White Square, the poems subtlylengthen, the pace slows, the tone becomes more pliant:

To all the toys I broke in my escape

Here lies July month of the long feather

Tenderness of the sky fully Mediterranean

Talkative headline of the desert

How does one swallow indifference and plague

My mouth would be a grave but does not know how to lie

Sad upheaval of thaw in the bovine darkness

Sperm of black pudding on the childish beach

Winter

Here we see many of the habitual sites and motifs of the earlier poems—the animal imagery, the beach as the emblem of transgressive exchange—but the slower pace allows the speaker and reader to look both forward and backward as the lines progress, and the interrogatives are more searching, leaving a longer, more uncertain taste in the mouth. Against this, the Surrealist penchant for novel juxtaposition—”July month of the long feather,” “Talkative headline of the desert”—works like an aromatic tickling molecule which must be held in the throat along with every other flavor, entailing an acquired and adult taste. These poems feature truly wonderful clusters of lines like rewards for the reader, and for the poet, perhaps—the rewards of forbearance, of survival, of age:

You say no and the smallest object housed in a woman’s body

Arches the spine

Artificial Nice

False perfume from the hour on the couch

For what pale giraffes

Have I abandoned Byzantium

Here may be detected the prismatically elegiac position of this Egyptian-Jewish-English Francophone poet, exiled not from Jerusalem but from Egypt, not from the metropole but from the soi-disant provinces, identities and fortunes reversed and multiplied as in a hall of mirrors. Yet the music of the Psalms carries through the long distance, the music of loss. There’s a vulnerability to this mode that is also a kind of mastery, a commitment to the long work of survival: “The uncertainties of the dream place a heart on your face.”

The magnificent long poems of this late work—”Beyond the Swell,” “Winter Jasmine,” and “Black Holes” among them—propagate a subtle, bewitching snakiness still stitched with contradiction, especially around attraction and repulsion, conformity and non-compliance with ethnic and gender norms: “I am nothing more than the image on the backside / Of the working snake / A narrative’s Oriental Woman.” If the early poems seemed to stir to life in unlikely, uncanny ducts, the calmness and surety of Mansour’s late style makes the poems seem to levitate from the page. Their extensiveness entails a remarkable ability to bear oneself—to bear up under the vicissitudes of life, to bear the very presence of poetry—entirely different from the young impulse to set oneself and one’s poems on fire. It’s a tone that Moorhouse has been prepping us to hear from the earliest selections in this volume and now it unfurls, supple and entirely undiminished. As the volume concludes,

Happy in horror

The dead go on their way

Good natured and empty headed

And so the poem, and the book, and the body of work, hardly concludes, but trains its gaze on a new post-mortal vista.

In her translator’s note, Emilie Moorhouse offers an account of her motivation in translating Mansour, a project begun in the immediate aftermath of the #metoo movement:

women’s writing has often been judged as “too much”: too sultry, too frigid, too hysterical. If the pre-2017 world had not been ready for these voices, perhaps we had finally reached a moment where our culture could embrace them.

It is legitimately sad to read these words and realize how long ago 2017 feels, how historical this #metoo moment. It can be hard to connect to the hope and energy crystalized in that hashtag, given the backlash that has followed: relentless beat of misogyny, the capricious zeroing out of the rights of minoritized communities, the utter imperilment of the poor, of prisoners and migrants, the farce made of safety and self-determination in every part of the globe for all but the most vertiginously elite, and, in the Anglophone world as elsewhere, the techno-fascist constriction of sightlines. Grim times, the tightened pupil, the asphyxiate sky. But perhaps the very existence of projects like Moorhouse’s, initiated in that instant, entail a sustained and rising tide that will eventually overcome even these hostile bulwarks. Indeed, Moorhouse closes her preface with a resistant and resilient tone:

[Mansour] was an immigrant in post-war France and her favorite subject matter happened to be two of society’s greatest fears: death and unfettered female desire. . . . If writing for her was a conjuration of her own demons, then surely translating her words can serve to summon a spirit so keen to return from the world of the dead.

May it be so. And just as this ardent, well-honed collection coaxes Mansour’s “molecules of revolt” into jewel-bright, posthumous flares, so may surrealism’s many ambient, alert, electrifying molecules flare up to reverse the annihilating currents of our present moment with their inextinguishable methodology of inversion, reversal, non-compliance, and revolt.

Joyelle McSweeney is the author of ten books of poetry, prose, drama and criticism, including, most recently, Toxicon and Arachne (Nightboat, 2020) for which she was awarded the Shelley Prize from the Poetry Society of America, a Literature Fellowship from the Academy of American Arts and Letters, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. She is co-founder of the international press Action Books and teaches at Notre Dame. Her newest poetry collection, Death Styles, is forthcoming from Nightboat in April 2024.

This post may contain affiliate links.