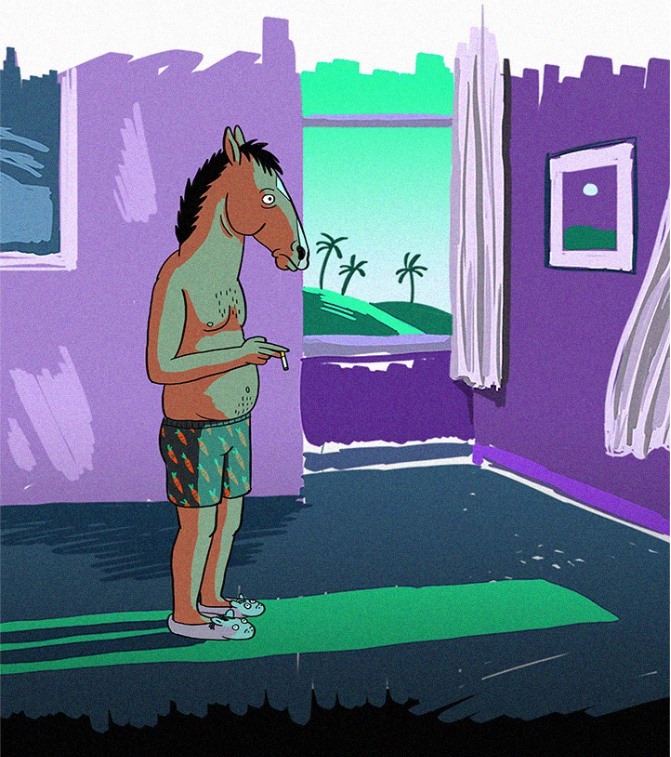

Lisa Hanawalt is the producer and production designer of BoJack Horseman, the Netflix series about a celebrity culture populated by humans and anthropomorphized animals. It stars a horse who made it big on a terrible ’80s/’90s family sitcom and now wastes away in his mansion. The supporting players include a hilariously self-destructive aging teen pop sensation and cat agent who plays with balls of string at her desk. The characters in Bojack Horseman’s universe are miserable, bored, and at war with themselves. The show’s creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg has claimed that the show was not meant to be the story of depression, but as Maxwell Strachan notes, the show has become the voice of depression, whatever its creator’s intentions. “Outside of a handful of series, depictions of depression in Hollywood have historically felt one-dimensional, as if writers Googled “depression” and decided it meant ‘sad.’” In BoJack Horseman, depressives have a hero in a figure who suffers from a complex disease. Bojack will forever be troubled by an abusive childhood. He will never conquer loneliness. He will never get to the bottom of who he truly is as a horseman. He will never get better.

Lisa Hanawalt is the producer and production designer of BoJack Horseman, the Netflix series about a celebrity culture populated by humans and anthropomorphized animals. It stars a horse who made it big on a terrible ’80s/’90s family sitcom and now wastes away in his mansion. The supporting players include a hilariously self-destructive aging teen pop sensation and cat agent who plays with balls of string at her desk. The characters in Bojack Horseman’s universe are miserable, bored, and at war with themselves. The show’s creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg has claimed that the show was not meant to be the story of depression, but as Maxwell Strachan notes, the show has become the voice of depression, whatever its creator’s intentions. “Outside of a handful of series, depictions of depression in Hollywood have historically felt one-dimensional, as if writers Googled “depression” and decided it meant ‘sad.’” In BoJack Horseman, depressives have a hero in a figure who suffers from a complex disease. Bojack will forever be troubled by an abusive childhood. He will never conquer loneliness. He will never get to the bottom of who he truly is as a horseman. He will never get better.

Lisa Hanawalt is also a comics creator and illustrator. Her first collection of strips, My Dirty Dumb Eyes, in retrospect, reads as series of notes for BoJack Horseman. It featured a series of anthropomorphic jokes, as well as sharp, digressive film reviews in comics form. Her new book Hot Dog Taste Test indulges a fascination with food, and by extension, with the various tragic bodily functions we all must face. Her books indulge the tragic sense of life, but they also remind you of the playfulness that runs through the entire mise-en-scène of BoJack Horseman. The world may cause us to hate ourselves, but it’s also filled with so many fascinating surfaces.

I interviewed Hanawalt about her new book by email in June.

Paul Morton: Historically, underground comics artists indulged either violence or sex in order to realize the grotesque. That tradition carried over into the rise of Fantagraphics and Drawn and Quarterly. Julie Doucet, after all, was one of your publisher’s first major successes. Did you look to these comics artists in order to learn how to depict eating and defecation?

Lisa Hanawalt: I try to avoid referencing other comics while I’m drawing — I don’t want to crib another artist’s stylistic approach instead of creating my own. Luckily, I eat and defecate often enough that I can illustrate from life and come at those subjects from my own perspective.

That said, I’ve always been drawn to comics that candidly explore grotesque and personal experiences. When I was in high school and I started reading work by Renée French, Phoebe Gloeckner, and Tony Millionaire, and it emboldened me to show my weird comics to other people.

On that note, I’m pretty sure most human beings spend more time eating and going to the bathroom than they do having sex or killing each other. Do you feel you are studying a major topic comics artists have ignored? Are there any comics artists who have explored eating or defecation that you would recommend?

I don’t think any of these subjects are anything new in the field of comics, or art in general, but hopefully my take on them feels idiosyncratic enough to be interesting! A lot of my peers make really great, personal work about body functions. Eleanor Davis, Laura Park, and Inés Estrada are just the first to come to mind!

Why do you think we are more interested in writing about sex than about food or defecation? Are food and defecation jokes childish, whereas sex is adult? And if so, did you find yourself indulging your elementary-school self when you made these comics?

I disagree that people are more interested in sex than in food — “food porn” is a thing! We aren’t supposed to openly discuss shitting in polite society, so making artwork that frankly portrays it is titillating. I think it’s called “desublimation” in fancy art-school terms, but it’s going back to a childish, playing around in our own muck state, and that’s why it’s as fun and appealing as it is repulsive.

Our culture’s concerns about food have a lot to do with aesthetics. We shame the overweight for supposedly not having a healthy relationship with food. And we talk about food in terms of a health crisis, in which Doritos are the new heroin. How much did you think of those concerns when you made your comics? I don’t see many bigger characters in the comics.

I wanted to push against the idea that comics about food have to be tied to concerns with dieting and weight. Not that there’s anything wrong with those topics, but I don’t have a fresh take on them at the moment.

I think my go-to body type for characters is “sturdy” and not super idealized, but I genuinely love drawing a range of shapes and sizes when I’m designing for BoJack or drawing a crowd.

Did every meal you ate become possible material for your comics as you were writing these stories? Did eating become a form of research?

Eating was only research when I was “on the clock,” so to speak, and either on assignment for a Lucky Peach piece or trying to generate ideas in my sketchbook. Most of my meals are just fuel, eaten in front of my computer.

“Menstrual Huts” is a feminist joke. In the rest of your comics I wonder if by indulging truths about the female body apart from sex, you are always offering a kind of feminist message.

I don’t mean to be combative but I’m genuinely curious — if “menstrual huts” had been drawn by a man, would you explain to him that his joke was feminist? I’m surprised that portraying the female body is still automatically political/feminist, while male bodies are neutral or comedic, etc. Menstruating is not a feminist act, it’s a bodily function. I hope you leave this part of the interview in, because it’s something that interests me.

I’ll explain my inspiration for “Menstrual Huts”: I was following Dwell Magazine on Twitter and every time they tweeted a picture of a gorgeous building, I thought it would be really funny to respond, “what a beautiful menstrual hut”! I’m a troll, but also I’d been thinking about how menstrual huts are still a tradition in certain cultures, and I could easily imagine rich Westerners appropriating and commodifying them. This is similar to how serving food in bowls is currently a trend in upscale areas, even though people around the world have been eating out of bowls forever.

On one page you put together a taxonomy of food. Under “Sassy Foods” you list, among other items, yogurt, gogurt, and Doritos. Under “Earnest Foods” you list eggs, ruffles and eggplant. When did you first, in your own life, start endowing different foods with different personalities? Or is this something you only started to do when you made comics?

I haven’t always done this, but the idea came to me randomly when I realized I could easily assign personalities to foods if I thought about it. So I scribbled that list and just sorted foods into the categories that instinctually made the most sense without second-guessing myself.

In your final pages you talk about our relationships to horses, thinking of the horse both as something to be ridden, but also as a possible source for meat. I feel this sums up human beings’ complicated relationship to animals. The more we relate to them, the more we become like cannibals. Has anthropomorphizing animals in your comics or in BoJack Horseman made you rethink how you treat them?

I’ve been anthropomorphizing animals since I first started drawing, so nothing has changed recently. I treat animals as well as I can. I fuss a lot over my dog, Indy, who I’ve had for ten years. When I ride horses, I try to have “soft hands” and communicate gently. That comic, “Caballos con Carne,” is fictional, so it’s very exaggerated.

Has making BoJack Horseman changed your views of celebrity? Do you watch films differently now than you did when you were writing your “film reviews”?

I still watch films the same way; those reviews were a window into my normal thought process while I sit through movies. I suppose I see celebrity culture a bit more up-close, working in Hollywood, but I don’t think there are any big surprises there.

The humor of your film reviews in your previous book translates in many ways to the world of BoJack Horseman. What parts of Hot Dog Taste Test crosses over into that world? What doesn’t?

My wordplay-loving, buttocks-enhancing sense of humor definitely creeps its way into the show in all sorts of ways, and meshes with the humor of the writers, directors and animators. I love to write silly menu items for the backgrounds of cafes and restaurants, and stupid t-shirt slogans for the characters.

Many critics consider BoJack Horseman to be a disturbingly accurate portrait of depression. Do you use a specific drawing style to convey that depression, something related to the “sturdiness” you have described?

I think the mood is achieved predominantly with the color palette and lighting. In the moodier scenes, we’re often trying to create a picturesque background (often a landscape or skyscape) that gets out of the way of the script and lets the words do their work. When characters are telling stories, we like to switch to a more children’s-book style of illustration (more shape- and color-based, less black line).

When I used the word “sturdy,” I meant that I tend to draw a thick, muscular physique, which is usually unrelated to the mood of whatever I’m working on.

You say that you have seen few surprises now that you’ve seen celebrity culture close-up. In spite of the bleak world of the show, have you grown at all more affectionate or maybe more forgiving towards celebrities — if not celebrity culture — since you started working on the series?

My feelings about celebrity culture haven’t changed, no. I feel the same about famous people as I do about non-celebs, which is that I’m forgiving unless they’ve been heinous towards anyone less powerful.

Paul Morton has worked as a cultural journalist in Vietnam, Bulgaria and Latvia. He also completed a Fulbright fellowship in Budapest, where he researched Hungary’s communist-era animation industry. His interview with Marvel Comics writer Brian Michael Bendis appeared in Ultimate Spider-Man: Ultimatum. He currently lives in Seattle where he is a Ph.D. candidate in Cinema Studies at the University of Washington. He can be reached via email at [email protected]. You can also read his blog My Thought-Dreams.

This post may contain affiliate links.