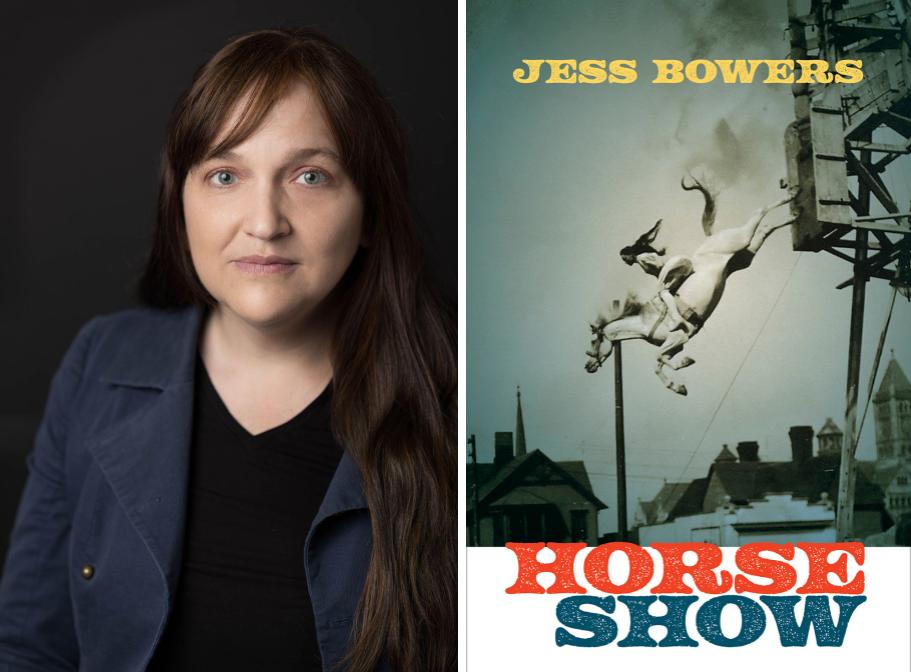

I met Jess Bowers in the grand Midwestscape of Missouri while we were working on our doctorates. Before encountering her work, I didn’t have too strong of an opinion on what I thought of as “animal stories.” I foolishly believed they merely ranged between stories for kids (Black Beauty, Old Yeller), political screeds we force children to wildly misunderstand (Animal Farm), fables (Aesop), or absolute nightmare fuel for children to prepare them for how shockingly strange adulthood can be (Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIHM). In other words, I remembered some of them fondly, but they were locked into the past. Formative, but from a time I grew away from.

But Bowers rejects that paradigm from the onset: stories about—or through the point of view of—animals are, at their intrinsic core, tales of people. Horse Show gives us a glimpse into a relatively unexcavated history, and in doing so dredges up the unnoticed losses: a handful of what must be countless unnamed horses, caught on film, on page, beaten and humiliated. But this is no castigation, certainly. Bowers’s prose weaves delightful, tongue-in-cheek humor, laughing at how we used to be, what we used to be. The hammer drops when she reminds us how we are still, achingly, the same.

Recently, I had the opportunity to email Bowers about her collection, the history of horses on celluloid, the balance of fictionalizing history, and the horse communities’ relationship to classic animal literature.

A.A. Balaskovits: The stories in Horse Show are fictionalized snapshots of how horse and human have interwoven histories, often to the detriment of the former. I was struck by how many of these horses I recognized but knew so little about, and so many I have never heard of. Your work asks us to contend with difficult memories: how we defined ourselves on the literal back of this creature. Is there a possibility of evolution of this relationship, or does the horse epitomize the careless violence of our past?

Jess Bowers: One of my major personal preoccupations is obsolescence, and I think the horse has been both a victim and a beneficiary of its own obsolescence. There’s a meme that makes the rounds in equestrian circles every now and then with a photo of a nineteenth century horse-drawn buggy next to a modern photo of a horse being hauled in a trailer, and the caption is: “Well played, horses.” But really it’s about the species’ shifting position in relationship to postmodern culture. The United States once used horses for transportation, construction, commerce, agriculture, energy production, sport, companionship, and entertainment—yet only the last few roles have endured into the twenty-first century. Unlike phasing out an inert piece of technology, when horsepower phased out the horse, a mutual relationship and lifestyle based on interspecies communication was lost and called “progress.” I wanted to honor that loss, which meant honoring a lot of individual losses, difficult memories, as you say. There’s a lot of violence in humankind’s shared history with animals, a lot of discomfort. I hope that, just as an honest war movie is inevitably anti-war, the tragic horses I write about move people to reconsider their own relationship to past violence.

Your comment about loss and progress, their inevitable union, made me think of “One Trick Pony,” your story about the filming of Jesse James, which highlights how pushing boundaries and loss have been intertwined in making art. Babe, the horse from the tale, ends up drowning in the water, her mane “sculled like seaweed,” and that’s the only image remembered from a largely forgotten film. I’m curious about that tension: does art require such sacrifices? Are they worth it, when the result is a body transformed by both terror and death?

Jesse James is objectively a terrible movie, which makes murdering that horse on film even more egregious! This isn’t to say that the horse’s death would be absolved if the film was a classic—but it could help make sense of why making the movie was more valuable than the horse’s safety. Neither the film nor the horse was treated with any care. Both were disposable, cogs in the Hollywood B-movie machine. One of the things that preoccupies me about all these faceless, nameless horses (“Babe” is an invention; the Jesse James horse’s name wasn’t even recorded) is the fact that their forced sacrifice was utterly pointless because it didn’t make the art better. The world would have forgotten Jesse James entirely if the movie hadn’t led to the creation of humane standards for film sets, but even that fact is just a footnote in film history.

Can you speak a bit about the process for researching these famous horses, and was there anything surprising you discovered? What was the balance between keeping close to the truth versus artistic perspective?

So many of these stories resulted from hours online spent pursuing one weird lead after another—so many primary sources have been digitized, it’s easy to follow a rumor or an anecdote to its root. For Horse Show, I tried to find now-obscure American horses who were once or should have been more famous, rather than the usual suspects like Secretariat, Beautiful Jim Key, and Seabiscuit. The most surprising thing I discovered out of the ideas that made it into the book was the story of Lady Wonder, who was owned by this woman who was such an incredible horse trainer she convinced Duke University scientists that her horse was psychic! That story is a good case study for how I combine fact and fiction. It contains actual transcripts from the horse’s “mind-reading” sessions with the researchers, real quotes from local witnesses, and I looked at old photographs of Lady Wonder and her barn for some of the details, but the characters’ personalities are mostly invented/extrapolated from the scant extant details about them. I am committed to the truth regarding the horses themselves—who they were, what they did, what happened to them. But everything surrounding the horses themselves is a collage of historical knowledge, my own observations/experiences, and details/dialogue/characters that I made up whole cloth.

One of the stories that struck me was “Stock Footage,” about Lucille Mulhall, the only woman in the world who accomplishes dangerous rodeo stunts (at the time, I assume). The American in me was prepped to cheer for her—a woman, breaking the danger glass ceiling! Huzzah for feminism!—yet you juxtapose her accomplishments with the indifference she has for the very animals who made her successful.

Lucille disappointed me, too! Much of her public appeal grew out of what her audiences saw as an “impossible” juxtaposition—Mulhall was petite and “ladylike” while shooting, roping, and riding better than cowboys twice her size. When I unearthed the “stock footage” in the title, I was struck by how roughly all the riders in it, male and female alike, treated their horses. I mean, I expected steers and goats to get handled roughly at a rodeo. It’s all about getting them roped or tied fast, so tenderness is in short supply. But early twentieth century America was already romanticizing the partnership between a cowgirl/boy and their horse, and Mulhall is just so brusque and cold toward her horses in these videos, especially little Tiny Mite, that I found myself wondering if she had any affection for the species, or just saw them as a means to an end, sentient platforms to showcase her own riding skill. I was also struck by how everyone who appears in this film is super self-conscious that they’re being filmed. It’s almost like a Lumiere short. Documentary, but not candid at all. These folks had secrets, I felt.

Can you explain your process for ordering the stories in the collection?

The “order of go,” as we say in the horse world, was hard to nail down because although there’s a lot of humor in these stories, there’s also emotional heaviness, death, and disaster. It felt important to make it clear from the start that this book would “go there,” so to speak. Because these stories are based on real events, they’re not your stereotypical “horse stories” where everyone wins the race and returns to the barn happy and well. So “The Mammoth Horse Waits,” the story that kicks off the collection, has this sort of circus barker, “come one, come all!” vibe while also being a clear tragedy. That was important to me, to establish from the start that spectacle and tragedy are thematic preoccupations here. Everyone at SFWP felt strongly that ending with “Of Course, Of Course,” my gonzo feminist reimagining of the classic sitcom Mr. Ed, had a momentum that worked for the ending. There are also recurring motifs that emerged naturally during composition—it turns out that lots of falling happens throughout obscure horse history. I wanted those moments to echo each other effectively. I hope they do!

Speaking of Mr. Ed, I thought the ending piece was phenomenal: a snapshot into a woman’s life who, though I watched that show as a kid, I barely remembered the wife was there. All these stories feel like snapshots of the forgotten, the footnotes—as you say. Is there any tension in balancing the historical with themes and ideas you’re working with?

As I wrote “Of Course, Of Course,” I was struck by how fundamentally the entire sitcom changes if Carol Post, not Wilbur, becomes the main character—if we see things from her point of view. Sure, it’s unsurprising that an American sitcom from the 1960s about a man and his talking horse didn’t give the female lead much to do beyond happy homemaking. But something about the setup in Mr. Ed always bothered me, even as a kid watching Nick at Nite reruns. In each episode, Wilbur does these insane, expensive, irresponsible things, and then blames Mr. Ed. But because the punchline hinges on Carol never knowing what we, the audience, do—that Ed really can talk—she’s just the stereotypical “nagging housewife” character, a foil to their boyish plans. Her only role is to misunderstand, complain, and interfere with Wilbur and Ed’s wacky antics, which the show wholeheartedly supports week after week. Carol’s presented as an antagonist when she’s the only functional adult in this relationship. I wanted to call attention to that dynamic because it’s a patriarchal paradigm I see repeated a lot in American families, both in media and real life. And it’s the swinging sixties! California! No kids! Get out there, Carol!

The tension you speak of is partly why I often use a third-person narrator when I write stories about TV or film. It lets me sort of press pause on the narrative to show the cultural baggage surrounding whatever’s happening at the moment. I like historical fiction best when it preserves truth from a clear perspective while also telling a good story and exploring the motives and morals of the people involved. In stories like “Of Course, Of Course,” “One Trick Pony,” and “Based On A True Story,” I had fun mining behind-the-scenes rumors and public records to show how the gender/disability/animal rights issues that are so apparent in these movies and TV shows today were systemic and production-wide—real choices real people consciously made back then, however awful they might seem now.

I have to ask, since I know you’re a Horse Gal yourself (does the community even use that kind of language?), how do you, and your equestrian community, feel about those typical horse stories? Was it your experience working with these animals that led you to write this collection, was it encountering the happily-ever-after, Black Beauty-esque narratives, or something else entirely?

LOL, we call ourselves “horse people,” mostly. “I’m a horse person,” I’d say. I’ve been riding since I was twelve, but I’ve been obsessed with horses since I was two years old, which is when I realized that dinosaurs were extinct and shifted my interest to large animals that I could ride. My horsey upbringing was rough-and-tumble. More of a galloping green-broke colts through the neighbors’ cornfields situation than a get-dressed-in-fancy breeches-and-go-to-shows scenario. I love how when I groom and tack up a horse, pick its hooves, cinch its girth, I’m completing rituals that have mostly stayed the same for hundreds of years, lost processes that would have been everyday habits for my great-great-great grandmother. I love the trust that develops between horses and humans if we’re patient and treat them with compassion and consistency. Some of my best friends have been horses.

And there’s a lot of overlap between the horse and book communities. Many equestrians are avid readers, and almost anyone at any given barn has read the usual YA suspects: Black Beauty, The Black Stallion, Misty of Chincoteague, National Velvet, etc. These books are the gateway drugs of the horse world, and most horse people I know share my love/hate relationship with them. There’s a lot of nostalgia there but also an understanding that those books left a lot out—often to protect young readers’ innocence. So I shied away from writing about horses for two main reasons: first, I genuinely thought “write what you know” sounded too easy, and second, yeah, the prototypical “horse story” tends to be pretty formulaic. A plucky kid meets a difficult but gorgeous horse; the difficult horse is magically tamed despite the child’s scant equestrian experience, and then the two of them go on to win a race or a championship or something, usually with the question of whether or not the kid gets to keep the horse hanging in the balance. Growing up reading these books, I knew life with horses had to be much more complicated, diverse, and difficult than that. And I wasn’t aware of any books that confronted the uneasy inequity of the horse/human relationship or explored situations where that relationship breaks down due to human arrogance. So I wrote what I wanted to read: a realistic horse book for adults that (I hope!) doesn’t rely on any of the genre’s cliches.

What were the works that influenced Horse Show, and what are you reading now?

Lydia Millet’s Love in Infant Monkeys, Michael Martone’s Seeing Eye, and John Haskell’s I Am Not Jackson Pollock are three fiction collections I found and read as I wrote Horse Show. All fictionalize history, pop culture, and film. They’re formally experimental yet foreground storytelling. On the other hand, I kept Black Beauty in mind as an influence I didn’t want. Horses weren’t going to narrate their own abuse in the first person. Not on my watch!

Lately, I’ve been recommending Bess Winter’s debut Machines of Another Era to anyone who loves historical fiction and heartstopping sentences. I just finished Gabriel Bump’s The New Naturals, a novel about a postmodern Black cult/commune. It’s subtly hilarious and features a huge cast of memorable characters, well juggled. And I started one of my Christmas books: Gina Siciliano’s graphic novel I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi. It’s this beautiful Fantagraphics tome about the Italian Baroque painter by an Italian American artist. Highly recommended.

What are you currently working on?

While researching Horse Show, I kept finding ideas about non-equine animals and saving them to write later, which is now. I’m throwing the gate open to welcome all manner of creatures from history and visual culture. Get ready for surprise guinea pig funerals and neon tetras riding on the Hindenberg. One new story I’m working on attempts to explain how and why The Brady Bunch, Wonder Woman, and The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe all feature dogs named Tiger who disappear and are never acknowledged again. I’m having a lot of fun.

A.A. Balaskovits is the author of Strange Folk You’ll Never Meet and Magic for Unlucky Girls. Winner of the Santa Fe Writers Project’s Literary Awards grand prize, her work has been featured in the Minnesota Review, Kenyon Review Online, The Journal, and many others. She currently lives in Chicago.

This post may contain affiliate links.