Cia Rinne’s first poem, written as a young student, consisted of three simple parts. “Answer this question carefully,” followed by two boxes, “Yes” and “No.” Even at this early stage we see a poet attentive to two distinctive trends in the modern treatment of language—to empty our expressions of all meaning in bureaucratic, formulaic forgetfulness, or, conversely, to pack our language so tightly that it strains the limits of semantic density if we just take the time to pay attention. It is obviously the latter tendency that interests Cia Rinne. In Wasting My Grammer, a joint exhibition with the Finnish artist Tanja Koljonen at the Berlin gallery Manière Noire until July 8, we see an excerpt of Cia’s work, small pieces that slip effortlessly between languages, between poetry and art, between visuality and sonority.

Cia Rinne’s first poem, written as a young student, consisted of three simple parts. “Answer this question carefully,” followed by two boxes, “Yes” and “No.” Even at this early stage we see a poet attentive to two distinctive trends in the modern treatment of language—to empty our expressions of all meaning in bureaucratic, formulaic forgetfulness, or, conversely, to pack our language so tightly that it strains the limits of semantic density if we just take the time to pay attention. It is obviously the latter tendency that interests Cia Rinne. In Wasting My Grammer, a joint exhibition with the Finnish artist Tanja Koljonen at the Berlin gallery Manière Noire until July 8, we see an excerpt of Cia’s work, small pieces that slip effortlessly between languages, between poetry and art, between visuality and sonority.

I met Cia at the Hamburger Bahnhof, a beautiful modern art museum in an old train station. Tucked in the corner of the museum’s voluminous main hall she was leading a small group through the poetry of Carl Andre, the enigmatic American sculptor and poet who is the subject of a retrospective at the museum. We retired to a small cafe afterward to discuss Andre’s significance as an artist who also worked across different boundaries, what it means to embrace brevity as a poetic principle, and the distinctive way in which Cia has been influenced by minimalist music. We were also joined by Andrew Mitchell Davenport, fellow interviews editor, who added a question at the end.

Michael Schapira: Could you describe the exhibition at the Manière Noire?

Cia Rinne: It is a joint exhibition with Tanja Koljonen, a wonderful Finnish artist who uses language in her work, whereas I write, but have also been showing my work in museums and gallery spaces. In that way, our works are related, and I was very happy about the possibility of our works sharing the space. Since the gallery space is rather limited I am showing an excerpt of a larger series 12 pieces. The pieces are all A-3 pages with carbon ribbon printed on an electric typewriter—carbon ribbon has a very strong imprint, which I like—and are all in English, German, and French.

The title, Wasting My Grammar, is one of my recent pieces. It seemed to suit the purpose very well. All of our works can be related to it in one way or another.

And how did you introduce the work?

We had a reading performance as part of poesiefestival berlin. Tanja read from a newspaper she had produced for the show, her first reading ever, and I read from notes for soloists, and my recent work called l’usage du mot. Both series consist of minimal texts composed in English, German, and French.

When you see recordings of your readings there is a clear influence from sound installations, and maybe the further edges of experimental music.

It is true that I love certain experimental music, and it is possible that this interest has affected the text pieces. sounds for soloists was actually made as a sound installation for a museum, with four loud speakers. The text and voice are mine, but the music and sound design are made by Danish musician Sebastian Eskildsen, so all kudos to him.

When people talk about their influences it’s common to just name authors. Do you distinctly come from a musical trajectory?

No, I am not a musician at all, but as much as I have drawn inspiration from literature, philosophy and arts, I have been very much inspired by minimal and new classical music, by Steve Reich, Terry Riley, John Cage, or Sofia Gudaidulina, Arvo Pärt, and György Ligeti.

Is it something that naturally occurred to you or was it a revelation that you had that this kind of music could have a distinctive influence on your poetry?

When I was exposed to that music I immediately felt very connected to it. It coincided with the time in which I was writing the first pieces, and the repetitiveness, the slight shifts, the lack of linearity was fascinating to me. If a tone, a word or a sequence of either is repeated for some time, you may find new qualities, and in music, there may be a slight shift. This is something I found very interesting, but it was not that I said, “this is my inspiration.” I would just listen to it, music as a muse as it were.

I think I might be misinformed on this, but do you do any work on dead languages and use those translations in your poetry?

No, which does not mean I would not like to though. I studied Latin for seven years at school, but I did not particularly enjoy it. The thing is that we learned Latin by translation, and we would pronounce it with a German accent: dominus servum vocat [In a thick German accent]. It was only after having learned Italian and other Romance languages that I ’understood’ Latin. I did not learn Ancient Greek, but I feel it would be easier to learn now that I have learned Modern Greek. I know the opposite is often claimed, but to me, the acquisition of a language is closely connected to getting used to its sonority.

I do translate at times, but it is nothing I consciously use in my writing. Most of the pieces however move between languages. In the middle of the piece there may be shifts in language, and though it sounds similar, the meaning changes.

I had a false memory in my head. I thought someone had told me that those in-between sounds were from ancient and dead languages.

Well, sometimes the text is more intelligent that the author. A semiologist in Athens found several signs and meanings I had no idea about. This is also interesting, to think that you have not worked through all the steps of meaning that come from your own work.

What does it feel like to be working with a Northern European, almost Baltic linguistic background with Swedish, German, Finnish, Danish, etc. Does that linguistic topography mean anything to you?

Oh yes, but the thing is I grew up in Germany with two languages spoken at home, and another one in school, and we had Italian neighbors. When I write a text it is usually English, German, or French. It has nothing to do with that I would speak them better or that the group speaking them is larger. It is rather that the works that inspire me are usually written in English or French. And these languages have similarities in grammar, so I find it easier to shift between them. As European languages, they have a common rhizome, and at times produce false friends because they give an illusion of being similar while they are not that similar after all. In a way, they are also quite abstract, or not too connected to a certain linguistic realm that they are written or spoken in, as would be the case with Swedish or Finnish or Italian for instance. But I do not decide which language to use in the text, it is in there already, maybe from a found fragment. You start working with it and something happens.

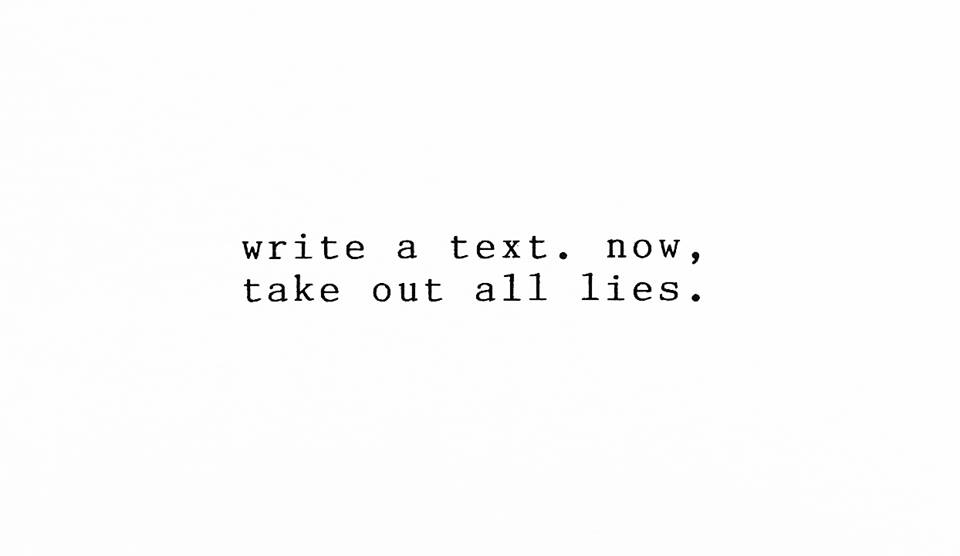

image © Cia Rinne, write a text, from the series l’usage du mot, 2016

I used to live in Quebec and there you see that language has the potential to be highly politicized. When you make these decisions they can be seen to have some sort of political intention behind them, but it sounds like from what you are saying that there is no political intention behind these choices. But in the context of Europe’s linguistic landscape is there any way that some political motives come into incorporating all these languages?

I do not plan it as any political statement—if you use all those languages as if they were equal however, it suddenly becomes political. We have this monolinguistic paradigm (Yasmin Yildiz wrote a book called Beyond the Mother Tongue: The Postmonolingual Condition). One of the problems in Europe in recent years, and more alarming now, is the curious belief that in one country there should be one language, one religion, one way of living. Differences should either be assimilated or eliminated. But reality in Europe has always been as heterogenius as heterolingual.

There are several realities existing at the same time. If someone has a different mother tongue that often has something rich to add that you don’t have.

But there is no explicit political statement in the pieces. The political content is almost one of the effects of our reality. And most of the pieces only work because they are multi-lingual. They don’t work if translated, or it would not be meaningful.

Maybe texts that are not simply fulfilling the task of what language is usually expected to do, as poetry does, make the reader more alert to language, and what it means; you might have difficulties using it blindly.

We just came from the Hamburger Bahnhof, where you had people read some Carl Andre poems. Talk about not knowing what the language is going to do. You look at them and they are visually striking but you have some difficult decisions to make in how you are going to read them. That creates another set of tasks for the reader. Do you like leaving a good amount of work for the reader to do?

Yes, I do think so, even though I have a quite specific idea of how my texts should be performed because I already have a melody in my head. How text is read aloud is maybe not the main interest, but when I perform other people’s texts that is usually the challenge. I am working with the Berlin Sound Poets Quoi Tête, and I find it to be liberating to work with other texts, scores, or performance ideas. It gives us the opportunity to test ideas, to play in a way I feel I would not be able to do with my own work.

At the Hamburg Bahnhof you said that you were nervous, or if not nervous you had to write something for what you were doing today, because they were filming it. But it seems like your work benefits from being filmed, or if there is a musician involved, or if you are slipping between these different languages. When did you think about recording your poetry not just in books, but incorporating sounds and a visual component?

The first piece that I wrote in school was, “answer this question carefully”, and there were just two boxes to tick, “yes” and “no.” I was influenced by Fluxus and Dada and had no idea that such pieces could be called poetry, so when I published it I thought people would look at it or read it. I collected these early pieces in my first book, and when my eventual publisher in Sweden asked me to read from it at a gathering one night, I said “it’s impossible, how can you read this? You can look at it, but it’s unreadable.” I had about five minutes to prepare, and I selected a few pieces that I thought were most fit for being read aloud. And when I did so, I realized it was not at all impossible. The following book, notes for soloists, is made concentrating much more on the sonority of the pieces. Even its name resembles that of a score.

The more often you read the pieces the more you get used to them and their specific sound. The texts are very short, and each has a certain rhythm or melody.

Although the very first book is more visual, showing the pieces in exhibitions started later, actually the first exhibitions involved sound installations, and objects, and then, the texts as such. I have three requirements for the pieces, content, visuality, and sonority. It takes me a long time to collect the pieces for a book, seven years for each book so far; in a way, it’s ridiculous to emerge with this really meager outcome.

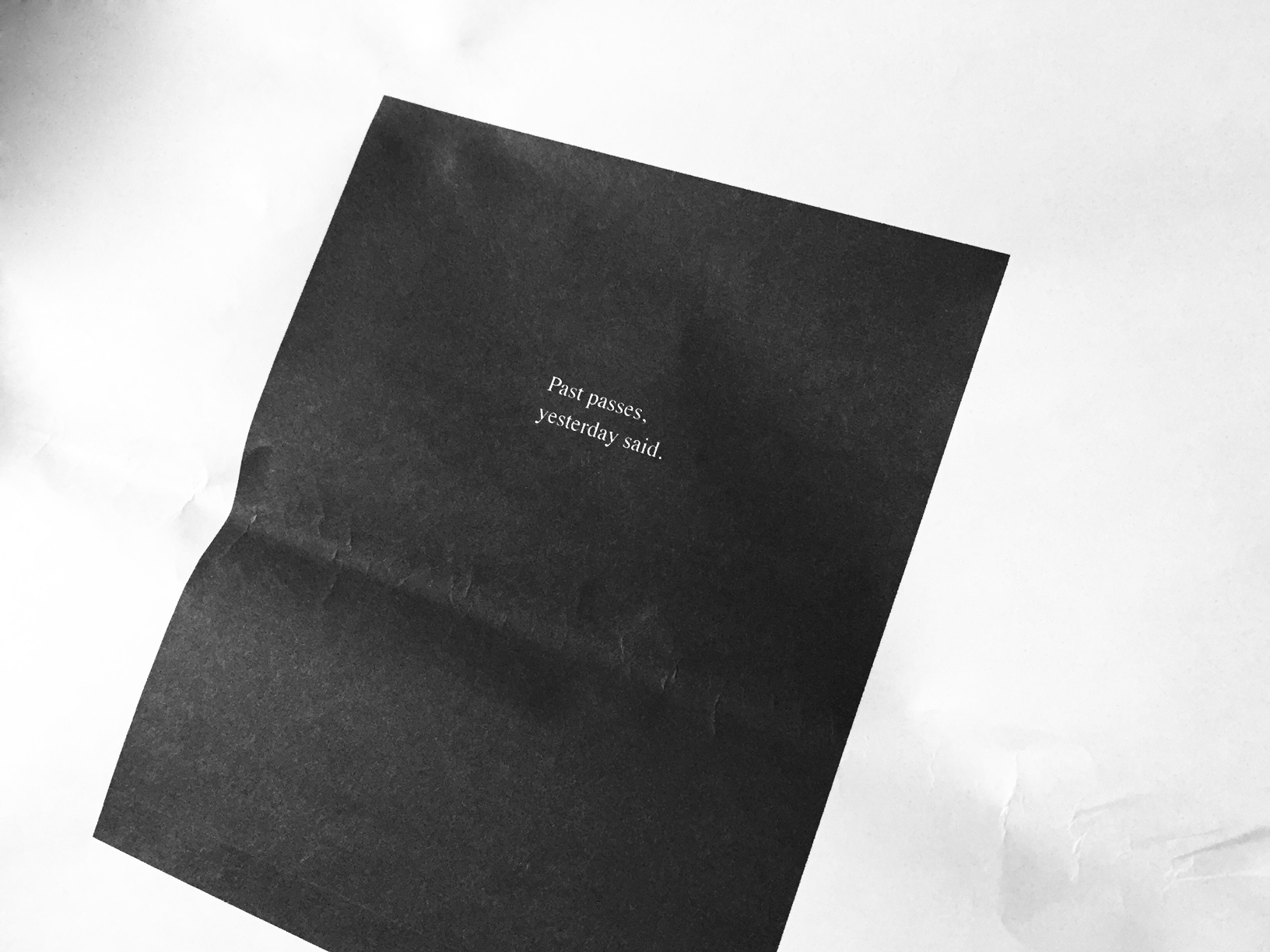

A detail from Tanja Koljonen’s Paper for Today, from the Wasting My Grammar exhibition at Manière Noire.

I was not very familiar with Carl Andre before today. You go into the main hall and see these sculptures, and the title of the show mentions sculpture, but in the third room of the exhibition you see all this text. It’s kind of a surprise if you don’t know anything coming in. I find it interesting when people are known for one artistic medium but also write, and these texts are either viewed as tossed off or are interesting because of the person’s greatness as a sculptor, or painter, or dancer.

There tends to be the curious notion that artists cannot be good in more than one discipline; there is no trust they might be able to push far in two directions, and so, one discipline becomes the dominant one simply by reception. For artists who write however, the situation appears to be slightly different if not quite the opposite; there is a lot of interest, although their work might not be read by a literary audience, but by people interested in their art.

Carl Andre is surprising because both sides of his practice share the same principles. When working with text, he breaks his material into its smallest parts—words and letters—and, applying his own systems or rules, he combines them in new ways. Similarly, his sculpture works are put together from single pieces or elements. The materials and media would never be mixed; everything is kept rather simple.

Your poems are very short and condensed…

Yes, that seems to be the case. Even when I write longer texts I like them to be condensed, to reduce the text by removing everything that is unnecessary.

It’s funny because the most popular novels are exactly the opposite these days—Knausgaard, Ferrante, Krasznahorkai. But you like the discipline of shortness.

Absolutely. Maybe it is a self-conscious reaction to this trend. There is so much information out there. I was also studying philosophy and it was so complex, you had to read this whole work to understand anything. When I tried to understand complex issues, it always helped me to condense the theory into a picture or a few words. I think it came from that, to condense all these huge structures into a single formula where you can grasp and understand it.

Maybe as a piece of advocacy are there any poets that we might not know who you are very excited about?

This is always difficult. Do you know Lev Rubinstein? He wrote his lines, pieces, poems on the index cards of the library he worked at. Ugly Duckling Presse published his works in a great volume some time ago called The Compleat Catalogue of Comedic Novelties.

Andrew Mitchell Davenport: And what is the question you are constantly posing to yourself?

A question constantly lingering beneath the surface is one about responsibility. I often ask myself how I can combine it with my conscience to work with poetry and art. Sometimes, it feels like a luxury. I have been working on a project on the Roma for several years, and another one in post-Apartheid South Africa before that, and still feel strongly for human rights and those of nature. So I see myself a little from the outside when reading poetry and installing exhibitions. It’s all very nice, but the planet is being destroyed at high speed, and people are drowning in the Mediterranean…I often have to think of what Brecht said: “Ah, what an age it is / When to speak of trees is almost a crime / For it is a kind of silence about injustice!”

Michael Schapira is an Interviews editor at Full Stop and teaches Philosophy at Hofstra University.

This post may contain affiliate links.