I.

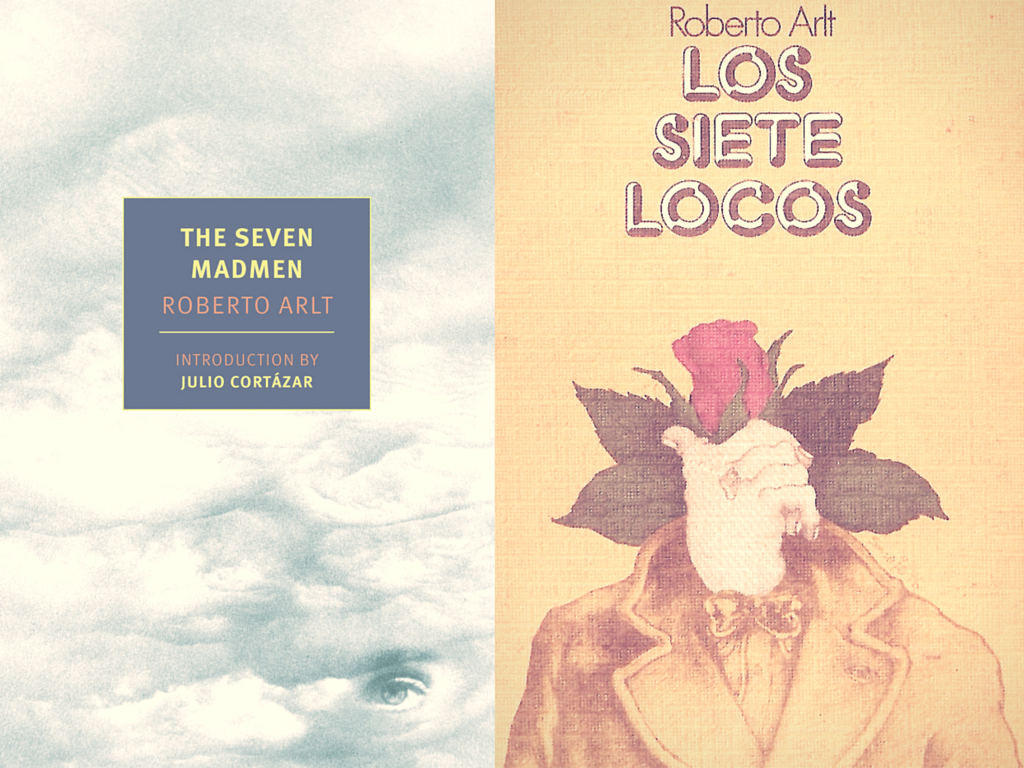

Before you read a single word of Roberto Arlt’s The Seven Madmen, you might see a quote attributed to Roberto Bolaño, on the back cover: “Let’s say, modestly, that Arlt is Jesus Christ.”

You can read this novel—just re-issued by NYRB Classics—without knowing what Bolaño meant by that, one of the many dozens of blurbs he’s left scattered throughout Spanish literature. You can ignore the blurb, and instead just open the book and read it; you can have an original relationship with the words on the page; it can be just you and this anxious, vexed, and splenetic novel about a man who embezzles from his boss, is fired, left by his wife, and turns to crime, murder, and millenarian fantasies. Maybe this is what you should do.

The Seven Madmen is a classic. Remi Erdosain is an unforgettable protagonist, as vulnerable and sympathetic as he is vicious and loathsome. While he might remind you of a character from Dostoyevsky (or Poe or Joyce), the psycho-geography he traverses is unique to this novel, and to its sequel (the still untranslated 1931 follow-up The Flame-Throwers). Arlt’s Buenos Aires is the underground exposed to the noonday sun, a mass of anxious confusion and everyday terrors in which everyone turns out to be the Lumpenproletariat. In Arlt’s Argentine capital, all are lost in the crowd and in their own confused fantasies.

When “like a caged beast” Erdosain “paces back and forth in his lair, surrounded by the indestructible bars of his incoherence,” he is a particular kind of horrifying everyman, the kind who—in their masses—make the city a playground for fascism. As Erdosain falls under the spell of character called “The Astrologer”—a cynical ideologue who wants to enslave the world for its own good, by telling lies the world wants to believe—Arlt dips into the well of hurt and fear and desire out of which one might build an empire. And yet for all its references to Mussolini and Lenin (or the fact that some have credited Arlt with “anticipating” the rise of Peronismo in Argentina), this book is not about the real world in any serious way. It’s not a political novel, but a philosophical one. Society is an illusion, the surface of an ocean of pain and longing that churns beneath, forever present, the only thing that never changes.

II.

Can you have an original relationship with a “classic”?

In 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson complained that “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face,” but that “we” could only seem to see “through their eyes.” And so, his plaintive lament: “Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?”

A great many white people in the Western hemisphere have been energized by this kind of fantasy, the “new world” in a nutshell: to cast aside the past and start again from scratch. When F. O. Matthiessen coined the term “American Renaissance”—in an influential book about “the Age of Emerson and Whitman”—the handful of writers that he canonized were all riffing variations on the same theme. Having no literary tradition themselves—no predecessors they cared to claim, and certainly no American classics—U.S. writers in the first half of the 19th century made that very lack into a virtue, praising themselves for their unmediated experience of raw, barbaric nature. The old world might bury itself in the tombs of its parents, but the new world’s novelty was that it didn’t build sepulchers for its fathers, didn’t get caught up in its own classics. Instead, as Emerson demanded: “Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?”

Many took up the challenge. Walt Whitman most prominently declared that we could and would start anew, while others – Poe, Thoreau, Melville Hawthorne – were carried along by the vision but were much more skeptical that it could be realized, or should be. Others who found Emerson’s vision less compelling, who stuck closer to home—people like Emily Dickinson, “Fanny Fern,” Harriet Beecher Stowe—tended to find themselves left out of the pantheon of literary fathers. It will surprise absolutely nobody to discover that Matthiessen’s American renaissance was a very masculine one.

In Argentina, something similar happened, at more or less the same time. There, the founding father was José Hernández, whose epic poem Martín Fierro used the figure of the gaucho to describe Argentina’s original relationship with itself. The gaucho was the Argentine version of the cowboy (just as the cowboy was a version of the gaucho), and, as in the U.S., it was only in the first part of the 20th century that this figure was retroactively placed at the heart of the national literary tradition. The martinfierristas—associated with the short-lived but influential avant-garde journal named after the gaucho—made Martín Fierro the voice of their own modernity, their originality:

“Martín Fierro knows that ‘everything is new under the sun,’ if seen with refreshed eyes and expressed with a contemporary accent…Martín Fierro has faith in our phonetics, our way of seeing, in our habits, in our own ears, in our own ability to digest and assimilate. Martín Fierro as artist rubs its eyes every moment in order to wipe away the cobwebs constantly tangling around them: habit and custom.”

But declarations of independence are never as novel as they must style themselves to be. They are all about proclaiming the origin point of a nation’s ascension to nationhood—just like all the other nations—and then vigorously insisting that no one notice the irony.

III.

Fascists are not well known for their appreciation of irony, and more than a few of the martinfierristas turned out to be fascists, when the time came.

IV.

Italo Calvino has what I think is the best definition of a ‘classic’: “classics” are books that we can only re-read, because we’ve always “read” them already—secondhand—long before we have the chance to read them ourselves. “Classics come down to us bearing upon them the traces of readings previous to ours,” as he puts it, “bringing in their wake the traces they themselves have left on the culture or cultures they have passed through.” A classic is essentially a social text, in other words, because it’s already been collectively absorbed and distributed and owned long before you get around to putting your own hands on it. And because our society has already read the classic, we too have already read it by osmosis. To “read” a classic, then, is not to discover something new, but to enter a long-running conversation that you’ve already been a part of, even before you became consciously aware of it.

Can you have an original relationship with a work that’s already a part of you, already half-digested and regurgitated, a meal fed to baby birds by their mothers? After all, you will have heard the thing about the windmills long before you ever read Don Quixote; Hamlet will feel like a play composed of quotations; Romeo and Juliet will seem like a patchwork of love story clichés; you will know many stories about shipwrecks before you get around to Robinson Crusoe; and because you’ll have read or watched dozens of imitators before you ever get around to reading 1984 or Brave New World, those dystopias will feel like anything but original. How could you read any of these books for the first time? Perhaps a better metaphor would be bacterial: when any of these literary germs enter your system for the first time, they will find that you’ve inherited a store of antibodies and immunities.

The strange thing about “classics,” then, is that they’ve become clichés long before you ever get near them.

V.

In the same way that you might know what the “Kafkaesque” is, long before you ever read Kafka or even put a name to it, Roberto Arlt’s work has long become “Arltian.” If you are Argentine, Los siete locos might already be a classic to you, and you may have already read it; you may have seen the film version from 1973, or the new mini-series; you may have read people like Onetti or Cortázar or Piglia, or any of the other writers who chewed up Roberto Arlt and have been regurgitating him ever since; you may have read Arlt in school when you were too young to understand what you were reading, and yet had him stuck in your belly, slowly digesting; or you may simply know about him, knowledge absorbed out of the penumbra of other people’s knowledge. You may know him without knowing that you do.

If you are Argentine, in other words, your relationship with Arlt could be as intimate and unarticulated as it was for Julio Cortázar, the great Argentine novelist whose introspective 1981 reflection has been translated and used as an introduction to the new NYRB Classics reissue. In the piece, Cortázar describes how he removed himself to a remote spot on the Pacific coast and rapidly re-read the entirety of Roberto Arlt’s corpus, attempting to re-discover anew one of the great authors of his youth. He was nervous at what he would find. “Everyone is familiar with those hopeful exhumations we finally perform on certain books, movies, or music,” he writes, “and the almost always disappointing results.” But Arlt does not disappoint: “Almost forty years after I first read them, I discover, with an astonishment that so closely resembles awe, to what extent I am still the reader I was the first time around.”

Arlt seems unchanged, “spared the almost inevitable degradation or dissolution that this vertiginous century has wrought upon so many of its creatures.”

VI.

Are you Argentine? Did you read Arlt decades ago and forget about it?

That introduction is a lovely mini-essay about Cortázar and his relationship to the writers of the 1920s and 30s—and about the classic that Roberto Arlt’s book had become by 1981. But if you need Cortázar’s reflections to understand why Arlt is important, or if you must follow Bolaño’s guidance to find what books to read, or if you are reading Nick Caister’s translation of Los siete locos as The Seven Madmen (and, indeed, if you are reading my review), then you are probably not Argentine, and The Seven Madmen probably does not feel like a classic. To you, the Argentina of the 1920s may come like a revelation: instead of rediscovering what you had half-forgotten, you may find Arlt’s Buenos Aires to be fresh and strange, a place you’ve never known, and would never have expected. As Remi Erdosain wanders the dreamscape of his tortured imagination—as it is projected onto the streets and apartments of Buenos Aires in the 1920s—the novel can feel like discovering a map to an underground labyrinth, buried under a city that has long since filled it in and forgotten it existed.

Again, perhaps you should simply read it; perhaps you should skip the introduction (and my review) and just dig into the book itself.

But in the same year that Cortázar repaired to the desolate Pacific coast to contemplate his literary origins, another reader proposed that there was no such thing as an unmediated reading experience. “We never really confront a text immediately, in all its freshness as a thing-in-itself,” wrote Fredric Jameson.

“Rather, texts come before us as the always-already-read; we apprehend them through sedimented layers of previous interpretations, or – if the text is brand-new, through the sedimented reading habits and categories developed by those inherited interpretive traditions.” (The Political Unconscious)

It might please us gringos to imagine that we could simply pick up a book like The Seven Madmen and read it, that like a shipwrecked sailor cast ashore in the tropics, we could quickly become self-reliant masters of our domain. But to read Arlt and find him to be like nothing you’ve read before, even that experience would come against a backdrop of inherited categories and traditions. If you find Arlt to be strange and unsettling, after all, it is because you have expectations for Latin American fiction that Roberto Arlt does not meet, because you come to Arlt expecting magical realism, the kind of hyper-intellectual formal experimentation of the Boom, or the capital L that Roberto Bolaño puts in the word “literature.”

Or it’s something else: no one comes ashore without baggage. If this book reminds you of Dostoevsky, Joyce, Kafka, Conrad—if it feels like a work of interwar modernism, like a very European book whose animating devils are Lenin and Mussolini, and utterly haunted by the specter of fascism—then it might not seem particularly “Latin American,” precisely because of the Latin America you expect to find, and don’t.

VII.

Maybe you shouldn’t try to have an original relationship with a classic. Maybe the idea of an “original relationship” is a viciously ignorant and anti-social fiction. After all, if you peel away American mythologies about coming face to face with reality on new world frontiers, you usually find a violent palimpsest where there was supposed to have been a blank slate (and where genocidal violence was used to make it into what it was supposed to have been, but wasn’t). The romantic fantasy of an “original relationship” with the world that Ralph Waldo Emerson had in the 19th century—that strain of idealism that defined the literature of the “American Renaissance” in the 1850s, sending Melville to the sea, Dickinson to metaphysics, and Thoreau to the woods—was always just warmed-over (and re-branded) barbaric romanticism of the sort that Jean-Jacques Rousseau had beaten to death a century earlier (or that Humboldt found in South America long before North American protestants ever decided to relax their self-hatred enough to go for a walk and take in the scenery). And before you could have an original relationship with nature—before you could husband the virgin land—you first had to make the land a widow, by murdering all the people who used to live there.

If the new world is, in a nutshell, the dreamer with eyes closed (“counting itself the king of infinite space”), then the Arltian is the very bad dream that troubles its sleep. At its heart, The Seven Madmen is about weak and resentful men who dream of being powerful. Remo Erdosain is an Argentine Walter Mitty: as he works his dead-end and soul-deadening job collecting debts for a sugar company, he lives a fantasy life inspired by Hollywood films, his minor genius as a self-taught engineer and inventor, and by his own strangely unhinged id. Early on, he dreams of being plucked from obscurity by a “melancholy, taciturn millionaire,” a character who he daydreams will peer out onto the street, recognize his mechanical ingenuity, and pick him out from the crowd, adopting him and giving him the money he needs to build laboratories and factories. Or he dreams of being seen on the street by a beautiful millionairess—a pale, sad, intense girl “driving her Rolls Royce just for the sake of it”—and he fantasizes that she would fall in love with him, and that they would sail off to Brazil on her yacht, there to live together in a chaste and melodramatic happiness.

These are his happy dreams, his more socially benign fantasies. But he also dreams of much darker things. “Walter Mitty” is essentially a comic short story—since Mitty’s daydreams release him to live his life unchanged—but as the story of Remo Erdosain stretches across two novels, it becomes a tragic farce. As Erdosain begins to act on his dreams, he follows them into the night: first he steals from his employers; then he kidnaps a friend; then he plots and participates in a murder. When his wife leaves him, Erdosain falls in with a messianic would-be cult leader, The Astrologer, a man who collects broken, resentful souls like Erdosain, and who has hatched a plan for world domination (somehow) involving brothels, gold mines, electro-magnetic inventions, all pasted together with resentful despair.

It’s a ludicrous dream, and a pulp fiction. But then, the irony of calling The Seven Madmen a “classic” is that it’s a notoriously poorly-written book: if there is one thing everyone agrees on, when it comes to Roberto Arlt, it’s that he lacks style. Even Arlt admitted it; in the introduction to The Flame-Throwers, he wrote that style required “comforts, income, and an idle life.” But while he “ardently craved beauty,” and felt the desire to “work on a novel that, like those of Flaubert, would be composed of panoramic canvases,” he ultimately strove to write like a punch in the mouth. “Today, amidst the racket of a social structure that is inevitably collapsing,” he said, “it’s impossible to think about embroidery.”

I’m not really sure what it means to call Arlt a writer who lacks “style,” unless we would say the same thing of Ernest Hemingway, another pulp modernist who thought boxing was a good metaphor for literature. Of course, Hemingway was ultimately another cowboy-poet, even if he learned to deconstruct “style” in Gertrude Stein’s salons in Paris. And if there is one thing Arlt never was, it was a gaucho. Neither was he a voice of authenticity: when his use of Buenos Aires street language was criticized for its inaccuracy, he responded that being born into the streets, he never had time to learn the street language properly.

Roberto Arlt was always very attentive to this kind of irony. Remi Erdosain is a deeply Joycean flâneur, while Arlt’s previous novel, The Mad Toy, gives us a portrait of the artist as a young thug. But Arlt’s Joyce is always half-glimpsed, at best; though we can presume that he read Dámaso Alonso’s 1926 translation of The Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, Arlt died before Ulysses was ever translated into Spanish, and he famously railed against the way it had become a fetish object in Argentina’s lettered society. Arlt couldn’t read English, but the way Joyce was taken up in Argentina, in the 1920s, was remarkable: after Jorge Luis Borges reviewed Ulysses in 1925—and translated a handful of the final pages into Spanish—this book would become the vanguard of Argentine modernism almost before it arrived in France. Like a great many in the well-educated Argentine literary class, Borges spoke and read English as fluently as he did Spanish (and more generally, the libraries of European literature were open books to him, in their original languages).

If Borges read in the library, Arlt read in the street. And if Borges tells the story of Pierre Menard rewriting Don Quixote by immersing himself in everything Cervantes could have known or read or thought—an absurd ne plus ultra of scholarly rigor which ends up by re-creating the original, exactly—then the most interesting thing about Arlt’s Ulysses is that he decided to re-write it without ever reading the original. But Arlt was functionally (and bitterly) monolingual. His parents were Prussian and Italian immigrants, and he had spoken German at home, but his limited education and working class upbringing limited his literary horizons to Spanish and what was (badly) translated into it. And so he took his style from badly-written translations, and emulated books he had heard about, but never read.

VIII.

Like the occasional pretenses that Anglophile norteamericanos make of not being European, Argentine intellectuals of the early 20th century had to work hard to insist on their own indigenous traditions, retroactively creating predecessors like Martín Fierro, because the nation had become so very, very European. If Argentina had been a sparsely populated backwater in the 19th century, a vast grassland emptied of its indigenous peoples and filled with gauchos and cattle, the 20th century saw this rural settler society become a country filled with urban immigrants. By the 1920s, most Argentines were foreign-born, especially in the cities. Argentina and Buenos Aires (like the United States) would be so utterly transformed by such an unparalleled wave of European immigration that it would become totally unrecognizable to its more nativist sense of itself. Thus, the gaucho: to give white ranchers a position of centrality to the culture did the same thing as placing the white cowboy at the center of U.S. culture in the same period: putting the emotive center of the national culture in the empty spaces of native genocide and white settlement, away from the disorienting babble of the immigrant cities.

Arlt’s parents came from Italy and Prussia, for example, and he grew up speaking German before he spoke Spanish. He is therefore “Argentine” in exactly the way he isn’t: unlike Jorge Luis Borges, say, whose ancestry is the Argentine equivalent of “came over on the Mayflower,” Arlt’s ancestors did not settle the pampas, and there is not a trace of the gaucho in him, or in his work. He grew up in working-class slums which he never romanticized: like most of the European émigrés who came to South America looking for land and freedom, his parents settled in the cities because the land had already been taken, because the vast cattle-country had already been concentrated in a very few hands and because the age of the gaucho (such as it had ever been) was over.

And so, Arlt’s Argentina has no trace of the open frontier to it, and is not a “new world” at all; his Buenos Aires is a polyglot and European metropolis, anything but a melting pot or a tabula rasa. It is a volatile witch’s cauldron of modernity, reflecting and refracting the convulsions of Europe itself, as a lumpen excess clogs the city’s streets and arteries, cut off from their roots but able to find no new ground in which to grow. It is therefore filled with and defined by the broken dreams, crushed spirits, and desperation of Europe’s great failure, the long and savage aftermath of the Great War.

This is a different story about Argentina than Argentine writers have tended to tell, before Arlt and long after. And this is what Bolaño meant in calling him “Jesus”: Arlt was the messiah of a different literary gospel, albeit a road mostly not taken. Arlt wrote one truly great work—the two-part novel of which The Seven Madmen is the first part—and then he died at the age of 42, in 1942; the same age as the still-young twentieth century. So much of the twentieth century had not yet happened when Arlt died of a sudden heart attack: when he published Los siete locos in 1929, the world economy had not yet crashed, the world had not yet been reshaped by World War II (and Argentina by the 1943 coup and the advent of Juan Peron); indeed, Arlt’s naturalist fabulism was written long before the “Boom” in Latin American literature would retroactively transform his work into a revered predecessor.

Arlt was the same age as Jorge Luis Borges when he died, but it would be Borges who would become the great Argentine writer. Arlt’s entire lifetime effectively corresponds to Borges’ “early” period. And though Borges was also the same age as the twentieth century, he kept growing, living and writing for another forty years, and he never stopped feeling contemporary, even now. Postmodern successors like Barthes and Foucault—and especially by the novelists and poets whose work became “Borgesian” whether they knew it or not—always seem to pull his work forward into the present. By contrast, to read Arlt, now, is be dragged back to turn-of-the-century Argentina, to a time when a global apocalypse was clearly on the horizon but when Mussolini had not yet become a joke, when Lenin had not yet been entombed, and when the word “fascism” had not yet become a catch-all term for political evil.

IX.

When Roberto Bolaño described Arlt as the messiah—in an essay collected in Between Parentheses—he means that Arlt was the martyr upon whose corpse a literary religion could be and was built. His death “wasn’t the end of everything,” Bolaño writes, “because like Jesus Christ, Arlt had his St. Paul. Arlt’s St. Paul, the founder of his church, is Ricardo Piglia.”

Cortázar remembers Arlt’s book as a classic; Piglia remembers it as everything but a classic, because his work is not dead:

“the biggest risk today is the work of Arlt’s canonization. So far it has saved his style from going to the museum: it is difficult to neutralize this writing, and there is no professor who can resist it. It is resolutely opposed to the petty standard of overcorrection that has served to define the medium style of our literature.”

The gospels of Piglia’s church are his novels Artificial Respiration, The Absent City, or his newly translated Target in the Night, though if you truly want to understand the Piglian heterodoxy, you need to go back to the first act of this apostle, his “Homage to Roberto Arlt.”

(Bolaño does not take communion at this church, of course; calling Arlt “Jesus” is a way of mocking Piglia’s devotion to his saint. “I often ask myself,” Bolaño continued, “what would have happened if Piglia, instead of falling in love with Arlt, had fallen in love with Gombrowicz? Why didn’t Piglia devote himself to spreading the Gombrowiczian good news?” As always with Bolaño’s quotes and generous blurbs, vacuous praise takes the place of the much more interesting story which is not being told.)

For critics like Ricardo Piglia, Arlt’s early death had made him perfect for canonization, a literary forefather who could be used to sidestep Borges and to chart an alternate and forward-looking path for Argentine and Latin American literature. As Piglia’s stand-in, Enzi, argues in Artificial Respiration, Borges was essentially a 19th-century author: he might have synthesized the antinomies of civilization and barbarism that defined Argentina as a 19th-century frontier, but his was still a literature suspended between gauchos and the lettered city, between Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s Facundo and José Hernández’s Martín Fierro. In Piglia’s account, Borges made it possible for Argentine literature to move beyond this suspension: after Borges, the structuring divide for Argentina would no longer be the country and the city, no longer gauchos on the pampas and libraries in the metropolis: as Argentina was flooded with European immigrants—like Arlt’s parents—the great antagonism would be class, the high and the stylish against the low and the vulgar. But like Moses, Borges would never enter the promised land himself.

For Piglia, then, Borges wrote in good Spanish—a precise and clear style that approached perfection—but the fact that Arlt wrote “badly” is what made him important. Because Arlt’s style was no style at all—an abrasively “bad” Spanish which Arlt blamed on the conditions in which he lived and wrote, the bedlam of the streets—his writing never became aesthetic, could never be placed in a museum. Piglia deeply distrusts style; if Borges’ writing was “preciso y claro, casi perfecto” it was because he was essentially estranged from his mother tongue, and this estrangement produced a desire for perfection. In the hands of the martinfierristas—and especially Argentine writers like Leopoldo Lugones or Leopoldo Marechal—stylistic perfection was an aestheticization of politics, frankly and unapologetically fascist. Theirs was the high style of those who would purify the dialect of the tribe, and cleanse the body politic of its unwanted excess and unsightly messes.

Borges himself was explicitly anti-fascist, of course. But Piglia was and is a great reader of the implicit and unspoken. For him, to write with style was to be a secret sharer with its enemy. And if there was one thing Arlt didn’t do—and there might only have been one thing—it was that.

Aaron Bady is a writer in Oakland and an editor at the New Inquiry, and tweets as @zunguzungu.

This post may contain affiliate links.