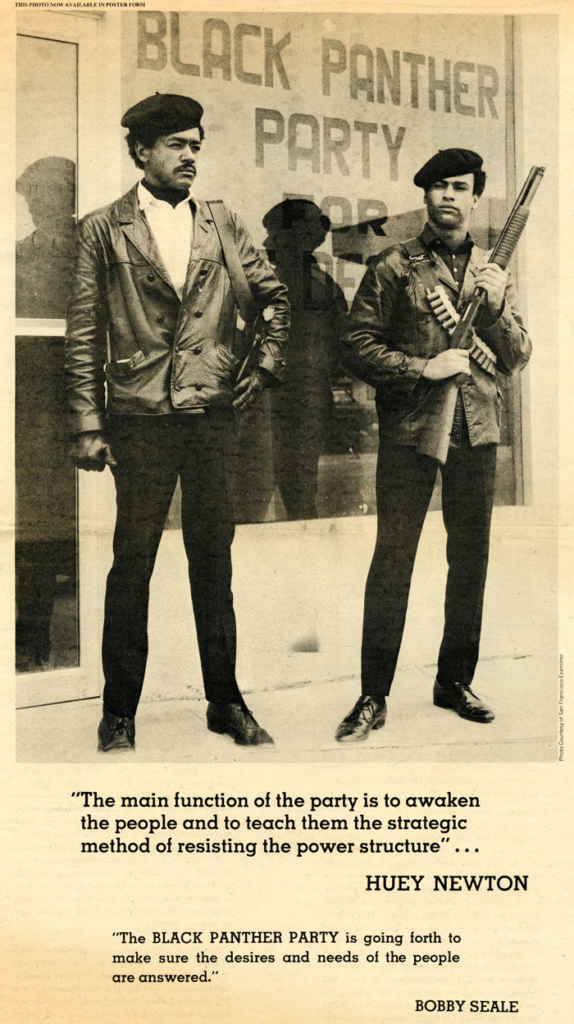

Sean Stewart was born in Kingston, Jamaica in the late 1970s, and thus does not fit the biographical profile of someone who would so expertly capture the feeling of America’s two great waves of the counterculture — the late ’60s/early ’70s and the late ’80s/early ’90s — from the inside. As pathetic baby boomers often put it, “you had to be there.” But, Stewart explains, “as a little kid all my heroes were outlaws, self-styled or otherwise,” so it makes perfect sense that he’d find allies in the Underground Press Syndicate, the Black Panthers, and the forerunners of hip-hop. Occupy gave us the language of the 99 and the one percent, but it’s better to be reminded that the man has always been the man and power, love, and respect should always be directed towards the people.

Sean Stewart was born in Kingston, Jamaica in the late 1970s, and thus does not fit the biographical profile of someone who would so expertly capture the feeling of America’s two great waves of the counterculture — the late ’60s/early ’70s and the late ’80s/early ’90s — from the inside. As pathetic baby boomers often put it, “you had to be there.” But, Stewart explains, “as a little kid all my heroes were outlaws, self-styled or otherwise,” so it makes perfect sense that he’d find allies in the Underground Press Syndicate, the Black Panthers, and the forerunners of hip-hop. Occupy gave us the language of the 99 and the one percent, but it’s better to be reminded that the man has always been the man and power, love, and respect should always be directed towards the people.

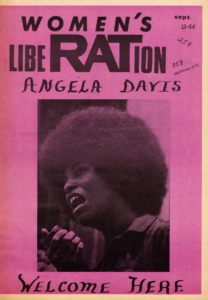

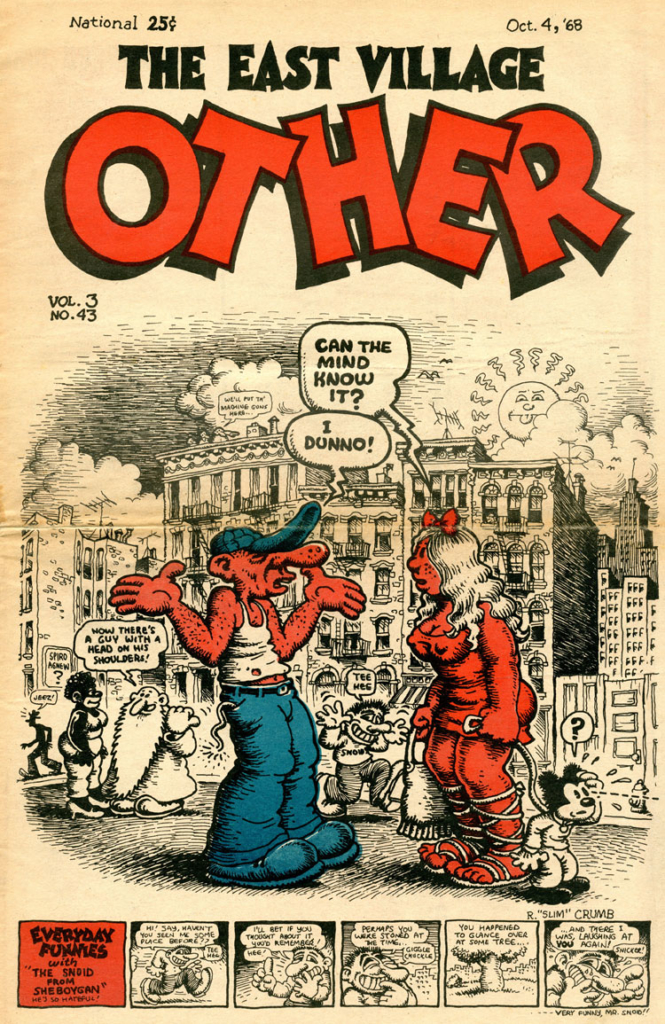

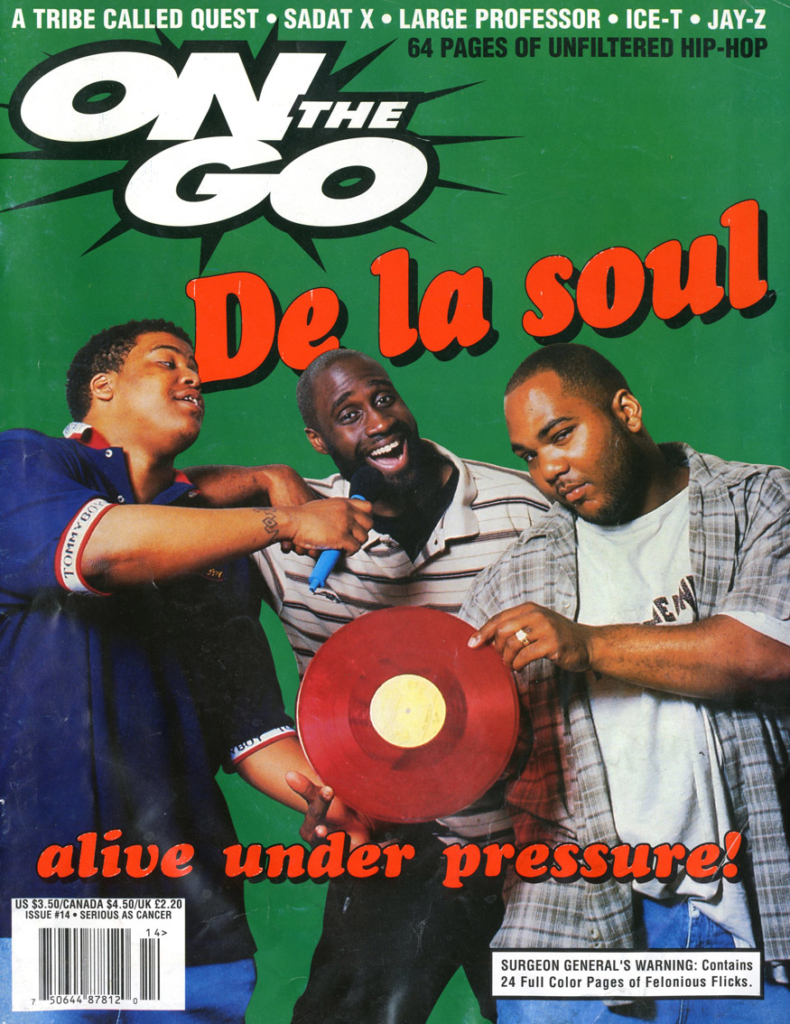

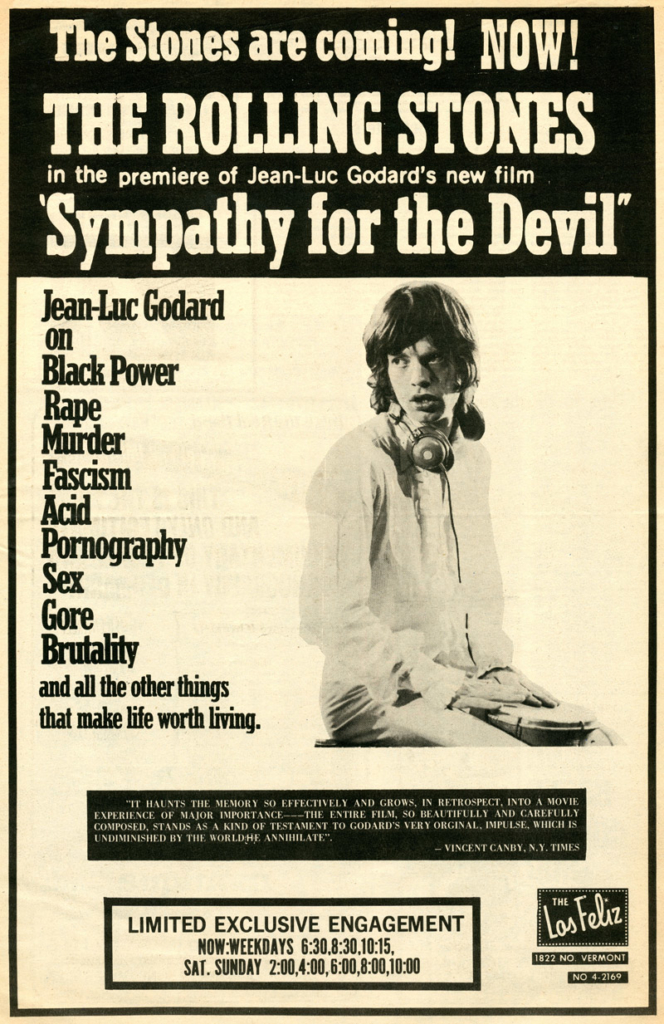

Stewart is the voice behind Babylon Falling, an online curatorial project that collects subversive, revolutionary, and oftentimes funny images from the countercultural past, which in many instances operates as a prescient echo of the present. In the late 2000s he ran a bookshop/gallery under the same name, which during its brief run served as a hub for Bay Area progressives and misfits. He is also the editor of On the Ground: An Illustrated Anecdotal History of the Sixties Underground Press in the U.S.. We traded emails with Sean about the origins of the project, the underground press, and the relationship between the counterculture and race relations in America. He was also generous enough to share some gems from his archive with Full Stop.

Michael Schapira: You were born in Kingston in the late 1970s. What path of interests, or specific things that you started to hunt down and collect, led you to all the magazines in the Underground Press Syndicate? Did a broader interest in the counterculture lead you to the underground press or vice versa?

Sean Stewart: As a little kid all my real life heroes were outlaws, self-styled and otherwise, and of course growing up I was a little troublemaker, so I was primed to identify with the sixties youth rebellion from early. Over the years I picked up old underground newspapers wherever I stumbled across them and when I opened my bookstore and gallery in San Francisco, actually meeting and chopping it up with veterans of the sixties counterculture plunged me deeper into it. That’s the straight line, but truly there were so many little connections or points of reference that sparked my interest in the era that it would be difficult to unwind it all to find that one jumping off point.

Jesse Montgomery: How did you start collecting these images and what did that process look like? Are you scanning these from personal collections, does a physical archive exist, do you get them from other folks? When you put together an anecdotal history of the Underground Press (UP) titled On the Ground, what did that involve in terms of getting in touch with editors and writers?

I personally scan every image from my own collection of magazines, newspapers and ephemera. They come in from out of state digging trips, flea markets around NYC, as gifts from OGs, and of course a steady stream rolls in from eBay. Getting in touch with people to interview for On the Ground would have been impossible without Emory Douglas, Billy X Jennings, and Thorne Dreyer, who were instrumental in vouching for me and connecting me with their networks.

Jesse: Could you say a bit more about who some of the folks you mention (Emory Douglas, Billy X Jennings, Thorne Dreyer and their networks) are and what the process of collaborating entailed?

Sure. Emory Douglas was the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. He was one of the first people who agreed to participate in the project and having him on board made a ton of other people feel comfortable talking to me. No one sent me scans, but like a madman I actually flew cross-country with a large format scanner in a duffle bag to scan papers at Billy X Jennings’ It’s About Time Archives in Sacramento. We did a formal interview and then we chopped it up for a few hours while I scanned papers. I probably only used a handful of the scans from the afternoon and the craziest stories came after the tape recorder was off, but it was by far one of the highlights of putting the book together. In Austin Thorne Dreyer put me in touch with Jeff Shero who took me over to the South Austin Museum of Popular Culture where I met Michael Kleinman. We did a great spur-of-the-moment interview and he happened to have a full run of his high school underground newspaper with him. I couldn’t believe my luck. I was so hype when I left. When I got home I realized I fucked up the audio and scanned the papers in at 100 dpi. Almost completely unusable. Now that I think about it, all of the in-person interviews were amazing because everyone showed me personal artifacts from the era and I actually took pictures along the way, but other than a studio visit with Spain Rodriguez, I never did get around to posting any of that material.

Jesse: Did putting together such an intimate reflection on the movement as On the Ground change the way you thought about your own project at BF?

BF has always been an outlet to share stuff that I thought was cool with like minded people. That hasn’t really changed, but having the opportunity to sit down with veterans of the underground press definitely helped orient me as I continue to sift through everything from this distance in time.

Jesse: Who is into this stuff these days (both UP and hip-hop mags)? Offline? Online?

I have 177K followers on Tumblr, so I know the interest at least in what I put out there is really diffuse. Beyond that I don’t monitor metrics, but my ideal audience is anyone on an overnight Greyhound with bricks in the backpack between their feet.

Jesse: I’m curious what it means to look at these images from the ’60s/’70s (and to a lesser extent ’80s/’90s) today. One of the things I think is so interesting about looking at BF, and this comes up toward the end of On the Ground, is the nagging narrative that the magazines eventually disbanded, dissent movements were squashed, the “sixties” ended, etc. — that all these radical experiments ended in failure of one kind or another. This is pretty much a trope-ism these days, but it’s a powerful story and I’m curious whether it’s possible to separate these images from that story. Has this project given you any insights into the way we think about, remember, and misremember the past?

Definitely. One of the original motivating factors for collecting the papers was bridging the wide gulf between the official narrative about the sixties counterculture and what I was actually seeing represented in the underground press of the time. And to your point, reinforcing the fluidity of it all is crucial, but I’m not an evangelist and I’ve never been interested in documentation in the traditional sense. To me, the key is encouraging and empowering people to interpret the history in ways that are relevant to their lives now. Beyond that, I’ll take a rich folklore within radical communities over good history from above any day.

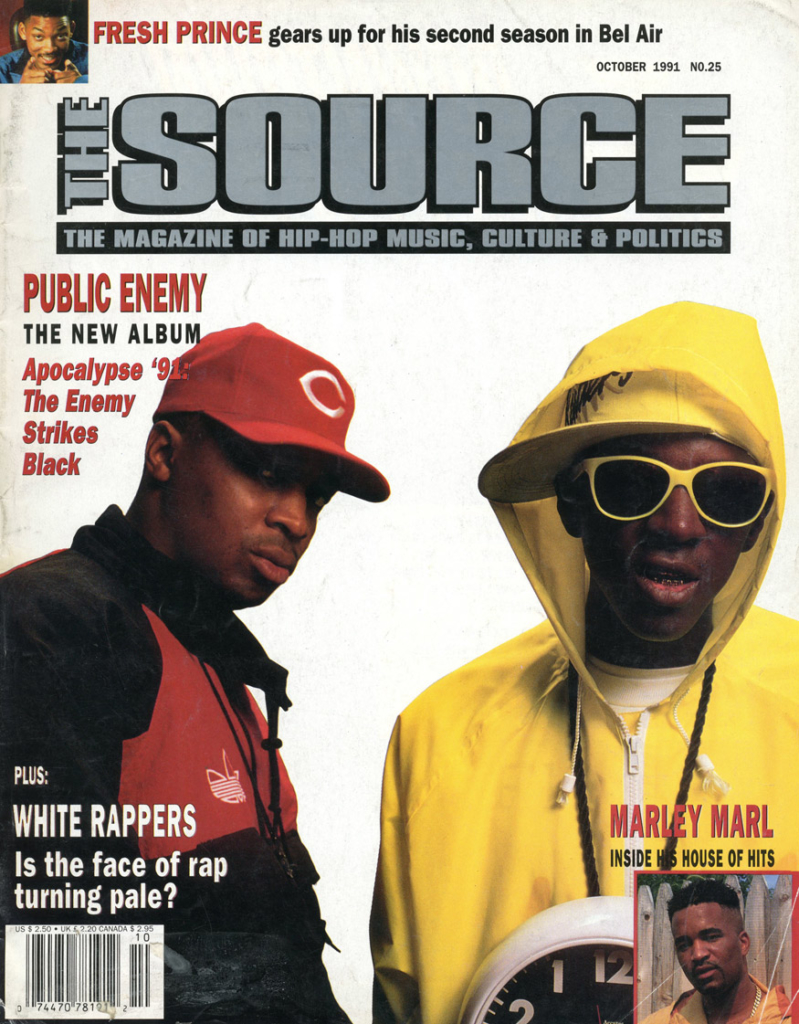

Michael: Fluidity in mind, your answer makes me wonder how the UP stuff found points of relevance for you, especially because you were born after one wave of the counterculture, but essentially grew up right alongside the birth of hip-hop, and the aesthetics of the two can be very different.

They seem incompatible on the surface, but when you check it out, hip-hop’s founding fathers grew up in the sixties so the connections to the era run deep even though they aren’t always so visible. Remnants of the counterculture found their way into the hip-hop DNA through the rock and roll, funk, soul, and r&b records filling DJ crates in the early days, and shades of the Panthers and Young Lords could be seen in the Universal Zulu Nation. Even underground comix reappeared, showing up in letter styles and the Bode characters adopted by second generation graffiti writers. Without ever connecting those dots, I was in Kingston collecting Mad magazine, wearing out pause tapes my god brother made me and catching the occasional episode of Yo! MTV Raps via satellite at rich girls’ houses. Jamaica gained independence in 1962 and by the time my generation got to high school the curriculum was infused with an anti-colonial, or at least non-imperial, perspective and so talking about the history of third world liberation movements was something that was pretty mainstream when I was coming up. At the same time my family was spending long weekends at a campground on the beach in Negril where I was soaking up anecdotes about the sixties counterculture from the former smugglers and leftover hippies that frequented the place. In college I started running with some kids that were enamored with the psychedelic side of the sixties and everything came full circle.

Michael: Most of the stuff on BF is drawn from the ’60s and ’70s, but there is also a bunch of ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s hip-hop stuff, and when you see all that together you get the feeling that the counterculture, from the underground press to album art, has always been way ahead of the mainstream on race. The hip-hop stuff seems natural and seamless next to the hippie stuff, which I wouldn’t have initially expected. Do you see the counterculture as one of the rare places where we can actually see a kind of racial equality in practice?

For sure the counterculture is always leading the mainstream by its nose on ideals, but I don’t know that the counterculture is ever out of range of the racist state apparatus. There might be some measure of equality possible on the edge, but I never saw the counterculture as a place distinct from the marketplace.

Jesse: The underground presses had their individual aesthetics, but they also syndicated comics and other content (I believe the Underground Press Syndicate helped out with this). Do you think it’s fair to call the art style put forward in these rags a distinct, popular style? What makes these images so evocative of their times?

I wouldn’t be qualified to make that determination but it was, like you say, evocative of its time. I think it was just pure earnest innocence along with some chemical assistance pushing everything along.

Michael: There’s a lot on student activism and black power on the Tumblr, and in the past couple of years you’ve seen both come back to the Bay Area (mostly in Oakland now though). You closed up your shop in 2009, but did you get a sense that these folks were still around? Did they come by the store?

Yes! Our events really brought together different generations of radicals and artists. Some of the greatest people I’ve ever met walked through those doors and I’m still in touch with many of them and many of them are still in touch with each other. Now, you can’t draw me out, but for sure I can say some Babylon Falling extended fam is out there on the front lines.

Jesse Montgomery is an editor at Full Stop and a graduate student in the English department at Vanderbilt University.

Michael Schapira is the Interviews editor at Full Stop and teaches Philosophy at Hofstra University.

This piece originally appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly Issue #2. The Quarterly is available to download or subscribe here.

This post may contain affiliate links.