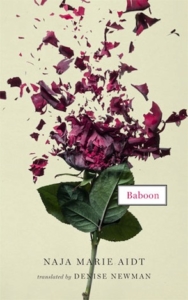

[Two Lines Press; 2014]

[Two Lines Press; 2014]

Tr. by Denise Newman

Naja Marie Aidt’s Baboon, translated by Denise Newman, fits firmly, disconcertingly between the straightforward and the openly, unrelentingly strange, whether in plot (or lack thereof), character, or prose. This purposely in-between that is often the most unsettling, and relatable, even if you don’t want it to be. Her stories disrupt well-being yet are utterly humane. Points of despair are reached in both body and spirit. There is also tenderness, moments between characters or granted by Aidt. They may slip by unnoticed, and may not save anyone, but are part of the world. There is a bizarre alchemy in reading where dread, cruelty, unhappiness on the page turn into pleasure in reading. In the stories of Baboon the science behind this alchemy is subtle and powerful.

This mastery comes in part from her ability to be concise. The stories in this collection are short and to the point. Each sentence is necessary, even as they take the time out for aesthetics, atmosphere, and place. She builds tension the way a horror writer does, but through the banal. Tension rises, then timed right, Aidt, gives an inch of relief. The prose has a leanness that doesn’t come from an MFA workshop, but from a clear-headed, bright-eyed individual. It’s the leanness of a solitary, long-distance runner, not of a cross-fit, gluten-free enthusiast. It is the type of deceptively simple prose that must be a challenge to translate, and Newman doesn’t falter.

Concise does not mean that the ground is always clear, that the way through the forest is open. Perspective is uncertain in many of the stories. We’re usually lost as to who the narrator is. Aidt abandons exposition, so characters are blanks, with background, gender unknown. This unknown pushes on the reader. With acceptance of the unsettled is established, she takes it further in later stories. Where gender was once suggested to be bent, it becomes bent. Entering her stories is a vertiginous drop into a consciousness, and there’s no choice but to accept this new place inside a mind. From there, a reader needs to find clues, markers that reflect back on an identity to reveal.

Baboon must have been carefully curated by Aidt. The stories align with each other at their heart, without reoccurring characters or any interlinks. The complexities of human relations, the pain and comfort, confusedly intertwined, dominate every piece. Nature is undeniable in its beauty, but also its force. In thought and in event, tone can turn as if suddenly struck. These turns are brutal, in the gasp necessary for a reader to catch their breath, stunning. This is a wonderful craft: to produce piece after piece, unique, but to wind up with a matched set, each making another more beautiful.

The opening story, “Bulbjerg,” establishes the ground for a reader. A small family is in the midst of a bicycle outing. At first, there is only an “I” and “you” watching over the child, Sebastian. It’s unclear who is mother, who is father; at first it isn’t clear if that even is the family set-up. The first sentences are focused on the “astonishing landscape.” Aidt lets the reader breathe in the land, creating the experience I hope for on a jaunt into the world on a bicycle. But this cannot hold. A pleasing landscape does not on its own create human warmth and happiness. That same natural world can in fact disrupt it. In a later story, the land is “hostile and parched” from the start. It’s inevitable for the dormant violence of the land to act on the people.

The family is quickly lost, aware of the intense heat. After noting it, Aidt turns from that threat to the weakness of the group: “We had a six-year-old boy and dachshund with us. The bikes were old and rusty, the danger of getting a flat imminent.” The move from this to Sebastian tiring is swift, and from his complaint to the father pondering his child’s base human awkwardness just as swift. Moments that are both jarring and smooth occur again and again.

The father assumes Sebasitan will develop an overbite, and his resentment for “all that with braces and headgear” is clear. He does not have empathy for how this will affect Sebastian, only an undercurrent of disgust. It’s one of the moments of individual brutality becoming the world’s. This mediation is interrupted by his wife standing over him “with a look of hatred.” The family gets more lost, the physical world more unbearable, and mother and father let honesty out of dark corners, turning to cruelty to match their suffering. The ways they care for their family are lost, with nothing said, nothing expected for a recovery. There is a breathing hole left for hope, for kindness from elsewhere, even if it couldn’t be enough for the family to last.

The next story, “Sunday,” plays out as if a brief response to “Bulbjerg.” Again, it is a family on an outing: a man, a woman, and two children in a carriage, older children at home. They bicker, but casually, without aim, comfortable in their disagreements. They share food and they joke. It’s not until the end of the story, when they arrive home, happily greeted by the children, that Aidt reveals this content, not joyous, couple have been divorced for seven years. In the laughter that leads to this, in the way the two echo each other’s “Seven years in November,” it’s as if an anniversary is being celebrated. This, their separation, is what lets them be healthy partners.

Aidt perceives with great clarity the intricacies of relationships, not just romantic or sexual, though they are prominent, and she does it with an apparent cool distance. The observations come with detachment, yes, but not utter disinterest. There is concern in her stories, care for the better qualities of people, or for flaws that are from weakness instead of cruelty.

Her distinctiveness and wonderfulness is what she leaves much unwritten and unspoken. There are gaps in all of her characters interactions. As in life, I never quite know what another is thinking, Aidt does not reveal every thought and feeling of her characters: they withhold from each other, and she preserves that privacy, or inability, fear, of expression. When I don’t know the guidelines of characters’ relations, the histories that build into reactions, I’m left in a fog. It creates a philosophy of the impossible other, not through explication, instead through a living, acting world. In “Conference,” one of Aidt’s strongest stories, the narrator, meeting a former lover, admits, “But I’m no stranger. And I am a stranger. It’s been so many years that we’ve definitely become strangers to each other, but we’ll never be complete strangers to each other.”

In “Blackcurrant,” the narrator senses something has upset his partner, so he asks what is wrong. The narrative breaks then, skipping to later in the evening. It’s only after this, and the following drift into a memory utterly distancing the narrator from his present, that the elision is clarified. The narrator is haunted by not knowing before what he now knows and this gap between him and his lover is what sends him to the reminiscence of a past relationship. These lacuna makes Aidt’s stories brilliant. The narrator is in a haze of confusion over what he just learned, and by cutting it out, preserving it for the two of them alone, we’re in a haze too. Though the reader’s lacuna is different than the narrator’s, we’re closer to his experience through it.

This impossible other is a fearsome thing to face, but Aidt knows that not facing it can be worse. What is unresolved becomes a source of terror, sometimes revealed in the story, other times a thread that dangles past the last page. If I want to pull on it, will everything solid come unraveled? A bizarre, violent encounter with a deranged man in the road leads to a couple turning from each other, from fear, shame, or anger — Aidt refuses, or finds it impossible, to explain.

By the end, a woman who was once a loved partner is treated as an object, and then it is her who wants to be hit. The begged assault is bloody and terrible. An insane encounter births this violence and every unspoken response, the turn from care or recognizing what happened, encourages it. What the whispered final words of the story mean to the couple cannot be grasped. These experiences of the absolute unknown, in the human, not the cosmic, are some of the most affecting in our lives.

The stories in Baboon could be pivotal moments in the characters’ lives or they could be part of the ongoing mundanity of life. These people may change or stay the same. As the narrator of “Wounds” puts it, “This is so incredibly banal, and yet it’s so important.” In seeing the moments as cut outs, the potential for encounters in our own lives to go either way is revealed.

In the banal and the important, Aidt shows people at their worst and their weakest. For all the secrets revealed about the men and women in the collection, I know so little about them. Aidt demands awareness of that. So how can I judge these people? Even as they are cruel, we see they are loving too, want to be loved, or are lost. Baboon is a rare work that fully embodies any message it contains. The fear of never knowing another, the pulls towards and from that other, the strengths and weakness of the human, are brought to the surface in the silences, through Aidt’s characters struggles with this life.

P.T. Smith is a writer and critic living in Vermont. He has also written for Three Percent, Bookslut, Mookse and the Gripes, and most recently Quebec Reads.

This post may contain affiliate links.