75 years ago, the Partisan Review sent out a questionnaire to a number of prominent writers, asking them about their work, politics, and identities. In 2011, we updated the questionnaire and elicited responses from 29 contemporary writers, including Marilynne Robinson, George Saunders, Roxane Gay, Philipp Meyer, and more. Now, as Full Stop turns four years old, we are, for the first time, asking our readers for donations, which will help us pay more talented young writers and take on new projects in the coming months. Click here to donate. As a token of gratitude and a preview of what’s to come, everyone who donates will receive a digital copy of the Situation responses. In honor of the release, Full Stop is publishing three new responses to the questionnaire this week.

* * *

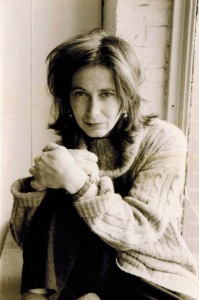

Chris Kraus is a novelist, filmmaker, art critic, and the editor of the Semiotext(e) Native Agents series. Her most recent novel, Summer of Hate, is a suspenseful love story and exposé of the criminalization of poverty in Bush-era America.

Chris Kraus is a novelist, filmmaker, art critic, and the editor of the Semiotext(e) Native Agents series. Her most recent novel, Summer of Hate, is a suspenseful love story and exposé of the criminalization of poverty in Bush-era America.

Does literature have a responsibility to respond to popular upheaval?

Not in a literal way. The question belongs to the Partisan Review era, when the notion of “popular upheaval” was less suspect and cynical, when upheavals weren’t expected to have been stage-managed. Still, even during that era, the most seemingly apolitical modernist writers responded to the spread of fascism in a displaced and poetic way. Sylvere Lotringer talks about this in his recent monograph The Miserables — the extremity of Artaud’s writing was an extrapolation from, or mirror of, the psychic atmosphere of that era. Any writing that doesn’t respond in some way to its time is autistic.

Do you think of yourself as writing for a definite audience? If so, how would you describe this audience? Would you say that the audience for serious American writing has grown or contracted in the last ten years?

I don’t know about the last question. It’s taken longer than ten years to shrink, maybe a century. Michael Silverblatt wrote a wonderful column for Good magazine about reading. He mentions Randall Jarrell’s 1962 essay about the Appleton school readers, produced for American fifth-graders in the 1880s, that included works by Coleridge, Dickens, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Thoreau and Poe.

So far my work hasn’t been taken that seriously in the literary world, but it circulates widely within the art world. The audience is younger, and has a different culture — the art world reads less fiction maybe, but more philosophy and critical theory. Also, the art world reads poetry.

Do you place much value on the criticism your work has received? For the past decade we’ve seen a series of cuts to predominant literary magazines and literary supplements, and in response, criticism has moved online. Do you think this move to the non-professional realm has made literary criticism more or less of an isolated cult?

It’s so gratifying when someone makes the effort to respond to my work in a thoughtful way. Intelligent criticism makes the work larger — it brings it to places the writer may never have thought of. There are very few professional literary critics any more. Books are mostly reviewed by peer writers or scholars. By the non-professional realm, do you mean blogs? Some of the most insightful readings of my work have been written on blogs — Jackie Wang’s Serbian Ballerinas; Kate Zambreno’s Frances Farmer Is My Sister. There’s very little difference any more whether a magazine is online or print media, in terms of its seriousness. Bombsite goes in a different, more challenging direction than the print magazine. And then, there’s this magazine to give another example. So the question of amateur v. professional maybe doesn’t completely apply.

Have you found it possible to make a living by writing the sort of thing you want to, without other work? Do you think there is a place in our current economic system and climate for literature as a profession?

No, not at all, but it was never a goal. I realized early on that the kind of writing and art I was most drawn to was not the most highly rewarded, so I made other plans. I teach on a visiting basis as much for the contact as for the income. I live mostly off rents.

Definitely, there’s a place in our system for literature as a profession — one complaint everyone makes is that contemporary culture is way too professionalized. I admire those writers who can live off their work, but it isn’t a benchmark. As two recent, very good books by Emily Gould (Friendship) and Choire Sicha (A Very Recent History) make clear, it is virtually impossible to live in a metropolitan city off the proceeds of literary writing. Maintaining the illusion that it might be possible, if one were just great and lucky enough, only perpetuates the tremendous class bias in American culture.

Do you find in retrospect that your writing reveals any allegiance to any group, class, organization, region, religion, or system of thought, or do you conceive of it as mainly the expression of yourself as an individual?

Neither one. Seventy-five years since this survey was written those categories and affiliations have all broken down. “System of thought” sounds like a euphemism for Marxism. Its artistic auxiliary, social realism, was practiced in good faith by a number of credible writers during that era. But even without those structures in place, I think everyone writes from a position, whether consciously or unconsciously. My writing reflects where I’ve been, what I’ve seen, what I’ve done.

How would you describe the political tendency of American writing, as a whole, since 2001? How do you feel about it yourself?

Was 2001 really a turning point? I think important changes occurred earlier on, when small commercial presses were absorbed by larger ones, and then acquired by media conglomerates. The definition of “mainstream” fiction became narrower. The fiction we publish with Semiotext(e) — novels by Abdellah Taia, Mark von Schlegell, Veronica Gonzalez Pena and others — are books that, twenty-five years ago, would have been published by smaller trade presses. But within the niche readerships that’ve developed partly online through people’s blogs, and magazines like Harriet, Full Stop and HTML Giant, there’s an acute consciousness of media culture, and a desire to produce work that bursts through that bubble.

This post may contain affiliate links.