Lede: No lede

In the first graf, mention that probably all writers, and definitely all readers, have very little time. My sympathies lie with freshly minted author @Benjamin_Lytal whose recent, rhetorically aimed tweet, asked “Q: What do you do for fun?” “A: I wake up early in the morning and I go to Oklahoma.” And since Benjamin Lytal’s debut novel, A Map of Tulsa, is already excerpted online here, reflected upon here, and favorably reviewed here, here, and here (by Gary Sernovitz), I will hold off on any kind of protracted analysis to really nail down the book. I will, however, still try to make good on a promise I made to one of Penguin’s publicity and promo lieutenants, @King_Langan, to whom I said that, if he were to send me a review galley, I’d be sure to write something up about it. Kick it off with a powerful line, like a first novel is like spring lamb, tender and pink.

Start the actual discussion of the book with a brief, bird’s-eye graf that describes just how Lytal’s Map winds around the not-so-wild Midwestern world of the author’s hometown. “As soon as I realized I didn’t want to,” Lytal said of landing the book in Tulsa, “it was obvious that I had to.”

Note that the plot, too, concerns a homecoming. Lytal’s narrator is a young poet, Jim Praley, who, over the course of the book, first recalls the duration of his sophomore summer spent re-exploring the landscape of his dissociated youth in the panhandle’s “Sooner” state, and then contextualizes those memories within his life after college, when he’s moved to New York, romanticized his past, and fantasized himself into an escapist narrative that takes him, eventually, back to Oklahoma.

(Try to avoid using commas like table salt.)

Use Oklahoma as a location, this will help in comparing the author and the narrator(-as-proxy.) In an essay called “Maps,” published in The Paris Review the day of the book’s release, Lytal writes “I am like a dog that I left behind in Tulsa, when my memories rot just right, I come running.” In the book’s early pages, Praley similarly recalls that “At college maybe I became conceited about Tulsa.” The word conceit means “formed in the mind.” Tulsa is thus a real place and also the epicenter of a nostalgia, with Praley “mentioning at just the right moments that I was raised Southern Baptist, had shot guns recreationally, had been a major Boy Scout—I may have agreed, when people smiled, and pretended that Tulsa was a minor classic, a Western, a bastion of Republican moonshine and a hot-bed, equally, of a kind of honky-tonk bonhomie.” It’s obvious but also not that every map doubles an original and is also an original itself. Words and their meanings accomplish this too.

At this point in the essay, deploy the review capsule, that A Map of Tusla is, at it’s heart, an excellent romance novel in which feelings and desires (aptly dubbed “longings” in the opening paragraph of Sernovitz’s NY Times review) emerge through several steps of written transference: author is remapped onto his character, who falls in love with a girl, who embodies the familiar-yet-exotic mystique of his hometown, which is simultaneously both a real place and a real place iced with memories from childhood, and on and on. Original experiences occur and then, through memory and language and writing, re-occur, again and again.

Remember text message from editor, “Your notes on Lytal’s book are OK. For starters, I think attaching some longer quotes would be coo. They could go anywhere—at the end maybe? Be like, “to be incorporated as evidence of (whatever)…”

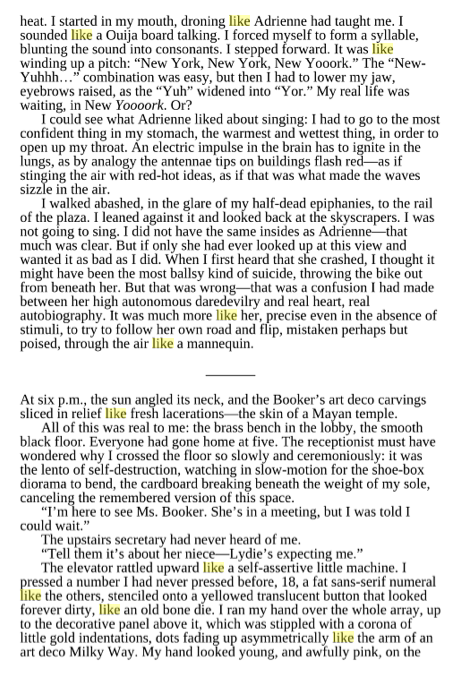

Establish that in Praley’s quest to understand his life, he tends to recount and explain past experiences as often as he has new ones. This tendency might demonstrate the writer’s urge to forge reality and imagination into a written word alloy… Lytal/Praley often articulates experience in long strings of analogy, a linguistic form of knowing by doubling. Lytal/Praley’s descriptive language unfolds an intellectualized sense experience, which spills out over many sentences and paragraphs such that the reader encounters the narrator’s life within a sea of rhetorical comparisons, like one time when Praley, for example, pegs a squirrelly man at a bar party to look “like Rimbaud.” I sometimes counted two or three ‘likes’ per page. Figure out a way to excerpt/display google books link. Lytal/Praley is a poet after all, and A Map of Tulsa is the debut novel by a guy who recently kicked off a New Yorker essay on Nabokov and Flaubert with the Knievelly first-line simile, “A first novel is like spring lamb, tender and pink,” and a book review at The Daily Beast, “Like fossil fuel.”

Now, having mentioned rhetorical comparison, go ahead and apply it to A Map of Tulsa. In Jim Praley, Lytal has combined the scavenging eye of a turkey vulture with the vocabulary of a Crimson bookworm. The result is a sometimes-bratty literary chimera who knows, for example, the trifold origins of the word “Elgin” to be a street in Tulsa, as well as some as well as some marbles “stripped off the walls of the Acropolis,” and “the place in Kansas.” For freshly Ivied Jim Praley, Tulsa is like a playground waiting to be explored by eye and comprehended by wit: a turducken lives a next door to a crone, white fish called sylphs coexist alongside houseflies atop a high-rise penthouse, the elysium is resurrect, and, in it, a girl smells “like a Band-Aid.”

In the beginning of the novel, Jim’s intellect has been unleashed and projected out into the world, where it mitigates his life and sets the book’s tone. This kind of heady narration feels familiarly liberal-artsy. It echoes a young adult life lived in the head and not in the heart. Experiences of sameness dominate, and repetitions abound: friends gather in shitty bars with fake ID’s, personas and akas; people dress similarly at dance parties and no one, like, cares. Such scenes, when rendered in Lytal’s analogy-heavy prose, consistently raise one scandalous question: in an age of elevated likes and comparison, what does it mean to love something — more specifically, someone? More questioning, etc., later on.

After only a few weeks back in Tulsa, Jim’s mental dominance grinds to a confusing halt when he re-meets Adrienne, a classmate from high school. This time around she’s incomparable, unlike anyone he’s met before—even his own memory of her: “She stood like a statue,” her nose “in outline, like a glimpse of what I had remembered,” next to Chase, a guy-she’s-sort-of-dating, who looks bored, “like the bull at the center of his labyrinth.” For the rest of the book, Adrienne, or rather some idealization of her, becomes Jim’s inspiration, his self-confessed muse. (Should I cut this? Too much narrative summary?)

Before the two speak, Jim’s friend Edith, tells him “I think Adrienne would almost like you.” But their first real encounter has more gravity than Edith apparently expected, perhaps because even in their brief conversation Like (an intellectual phenomenon) confronts Love (an emotional experience).

To be incorporated as evidence of the mind and the heart colliding in language:

Except for Edith and me, Adrienne was now alone. “What was your full name?” she asked me.

“Jim Praley.”

“Okay.” She took my arm. “Can I take him?”

Edith shooed me away, as if eager to get rid of me.

Adrienne steered me out into the hall. I felt mom-escorted, stiff-armed, institutionalized by these ladies.

“So Jim Praley. Are you having a good time at my party?”

“Well I love these hallways you have,” I said.

“They’re not really mine.”

“Right.”

“Why do you love them?”

“Because they seem so abstract.”

“Huh. Say more.”

“I guess because like the walls are plain, and with this carpeting—like they could be computer generated, repeating on into forever.”

“And you love that.”

“Yeah. Like it could all have just come out of your head.”

‘My head in particular?”

“Doesn’t it feel like I’m walking through a hallway in your head?”

Insert some boring etymology stuff here as a kind of break from exhaustive text recall. It’s relevant but also not that the study of the history of any word is yet another process of re-presentation, and therefore also an exercise in mapping. The word map, for example, derives from the Latin phrase mappa mundi, with mappa meaning some kind of cloth onto which representations of the world, mundi, were scrawled in abbreviating lines. Mapping is like writing is like knowing by analogy: you build a model, study it, then leave it behind to go find a real thing.

Near the conclusion, mention that the final line of the book—after the story has ended, in the Acknowledgements—is Lytal’s dedication to his wife Annie Bourneuf: “She knows what I know.” I don’t think this is a Paul Simon reference, I think it’s the highest praise of a poet for whom intimacy is an experience of the mind, intellect and mutual comprehension.

End with a beautiful line about how any life is also a line of words, and that each of these lines, like a map or a city or a book or a love, doesn’t have a clear beginning, and doesn’t really have an end either.

Peter Nowogrodzki is a writer living in western New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.