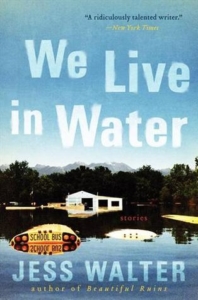

Like a fish stuck inside a tank of water, humans — i.e., creatures of habit — often find difficulty in venturing beyond what they already know. In his newest collection of short stories, We Live in Water, writer Jess Walter, author of Beautiful Ruins, illustrates with satire and playful social commentary how complacency serves as a boundary for people living within the cultural underbelly of America. Between a homeless man, a deadbeat father, a conniving drug dealer, post-Apocalyptic zombies, unruly step-fathers, inept mothers, jealous boyfriends and husbands, and hungry pawn shop dealers, Walter integrates wit, intensely reflective metaphors, and pop culture references to design his viewpoint of today’s American culture.

The world Walter creates is based on his own experiences as a child and adult living in Spokane, Washington, one of America’s most impoverished cities. In this world, every individual is either burdened by poverty, the childhood abandonment of parents, or the trauma of a recent divorce or breakup. In turn, what Walter illustrates through these traumatizing scenarios is the presence of the human mind and how one’s surroundings can persuade and claim dominance over it.

Walter powerfully portrays this message over the course of the collections’ twelve stories, primarily through the thoughts and voices of his main characters. In his story, “Anything Helps,” readers follow a-day-in-the-life of a homeless man named Bit. However, instead of initially establishing the story’s setting with a time and place, Walter launches the story by depicting the state of Bit’s mind via his own style of stream-of-consciousness writing — i.e., the integration of Bit’s distinguishable speaking style and vocabulary as seen through the third person perspective.

Although this type of storytelling feels like the first-person perspective, Walter actually develops a narrative which speaks from the third person. For example, while Walter illustrates in the third person a conversation Bit has with his son outside of his son’s foster home, Walter also conveys how depressing Bit’s life is from what feels like the first person perspective. Bit thinks, “It’s not like time passes anymore; it leaks, it seeps.” In turn, what Walter achieves by narrating in this fashion is his demonstration of the impact that internalized psychological agony caused by poverty, familial or relationship issues has on the common person. This theme, along with many others, is what drives the collection of short stories in We Live in Water.

Even though Walter addresses grim topics like poverty, childhood abandonment, or romantic injustices throughout his narratives, he implements his own sense of humor, which is dark, witty, and hewn with quiet vulgarity. This is especially apparent in his story, “Don’t Eat Cat,” in which Walter uses a futuristic setting involving post-Apocalyptic zombies to demonstrate one aspect of his multi-faceted commentary on the state of American culture, which is that, despite the modern inventions of genocide and chemical warfare, the world has always experienced cataclysmic chaos. “Sure, the world seems crazy now,” says the main character of “Don’t Eat Cat” when addressing the zombie dystopia of Seattle in which he lives. “But wouldn’t it seem just as crazy if you were alive when they sacrificed peasants, when people were born into slavery . . . when entire races tried to wipe other races off the planet?” On that account, by taking this apocalyptic message — that humans have been destructive for centuries — and integrating it into a world involving the well-known figure of the zombie, Walter develops a narrative that is both comedic and profound via his snarky descriptions of both the crudeness of zombie behavior and a world full of rancor, decay, and disease.

Although the twelve stories vary significantly in length — with some only lasting a couple of pages and others lasting at least twenty, each story possesses an infinite amount of wisdom. Despite the fact that Walter’s stream-of-consciousness narrative style invokes some confusion at times, all twelve stories are meaningful snapshots of moments in time. A divorced father sees his son for the first time in three weeks, a stepson begrudgingly takes his incarcerated stepdad to the hospital for his weekly kidney dialysis, and a homeless man gives his son the desired seventh Harry Potter book which he has long awaited. With isolated moments in time like these, Walter captures the essence of human emotion and suggests to readers that people living in the cultural underbelly of America should not be judged. Instead of judging their character, the circumstances that brought them to such a low state should be considered and empathized with. Like Walter writes in one of the stories, “Whole worlds exist beneath the surface [of the water]. And maybe you can’t see down there…but there’s a part of you that knows.”

This post may contain affiliate links.