Art Garfunkel is alive on the internet.

This is a complicated statement, and by no means easy to prove. It hinges on a difficult question: what does it mean to be alive on the internet? And, if we were to venture a guess about the parameters for internet living, how would we prove those parameters in the case of Art Garfunkel?

Kenneth Goldsmith once wrote “If it doesn’t exist on the Internet, it doesn’t exist.” For the purposes of this essay, let us consider this statement true, and never more true than for somebody like Art Garfunkel, who is simultaneously extremely famous and completely culturally irrelevant. Despite possessing one of the great tenors in pop music history — a tenor he has wielded with varying effect since 1970, when he stopped singing Paul Simon’s songs and started singing inferior songs by other people — Art Garfunkel is the sort of person who most people only know is alive because they have not yet heard news that he is dead.

Were Art Garfunkel to die, we would be immediately reminded of his life: his records, his acting career, even his poetry — more on his poetry later. But until the news of his death arrives Art Garfunkel lives in the specific limbo of the used-to-be-famous. He does not currently record, perform, act, or write, and in the absence of these public proclamations of self the only outlet he has to prove his continued existence is the internet.

There is a difference between existing digitally and being alive on the internet. Thanks to the ubiquity of public records and digital bookkeeping, most people in America do not have to fight to exist on the internet; we leave digital traces wherever we go, whether we choose to or not, because other institutions and people define our existence for us. In this, Art Garfunkel is no exception. Even if Art Garfunkel were to die tomorrow, we would still be forced to contend with his existence in the form of fansites, Amazon reviews, Wikipedia articles, all the detritus and internet flotsam that represents the online equivalent of dusty yearbooks and old telephone directories. We have gotten to the point in the digital era where our online existence rolls on longer than our physical one — as anyone with dead Facebook friends can tell you.

For all of us, Art Garfunkel included, being alive on the internet requires a constant imposition of personhood against this bare existence. What makes Art Garfunkel so special, so weirdly alive, is the truly odd way he has gone about parading his personhood on the web. Because, in an odd way, Art Garfunkel is ahead of his time, and we condescend to him at our peril. His lists are our lists: a list of books read through a lifetime, a list of songs recorded in order of their merit, a list of points in a journey across America.

Artgarfunkel.com — or, Art Garfunkel Walks Across America

Artgarfunkel.com — or, Art Garfunkel Walks Across America

On first glance, artgarfunkel.com does not look particularly alive. The design is painfully plain, the homepage just a list of generic news items that could easily have been collected by an underpaid press assistant: “Art’s Ten Favorite Architectural Spots in New York City,” “Audio Interviews on The Singer,” “Recent Appearances.” There are no animations or interactive icons, no fancy backgrounds; the only audiovisual components are several poorly imbedded YouTube clips of his days in Simon and Garfunkel and a PSA concerned with ending blindness by 2020.

It is a sad thing to be ruled by one’s own internet existence. This is the difference between living and existing on the web, between creating yourself and letting yourself be pieced together by someone (or something) else. Most of us would agree, for example, that you are not really alive on the internet if your presence is mediated by a PR team so incompetent that it forces you to shill your album “The Animals’ Christmas” on your personal website (just in time for the Holidays!), especially if you allow this PR team to refer to you as “legendary singer and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member ART GARGUNKEL,” and most especially if this PR teams feels it necessary to add on your public website that you believe “Paul [Simon] is part of my soul.”

Frankly, it’s embarrassing.

And yet — beneath this obligatory skin of mediated existence, Art Garfunkel lives! At the very bottom of the page lies a series of blue icons, full of strange information: “The G,” “Chronology,” “Library,” “Writings,” “Concerts,” and “Music.” When one clicks on “The G,” one finds — among the usual obligatory internet appendages like “Biography” and “Guestbook” — an icon entitled “Walk Across America.”

Click “Walk Across America” — you’ll be glad you did.

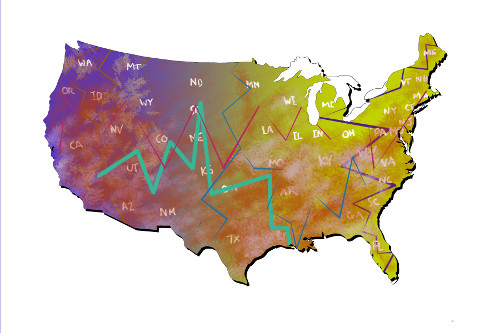

Design-wise, “Walk Across America” is just as poorly rendered as the rest of the website. The top of the page features a pixilated image of the United Sates with a gently sloping line drawn across it; by following the line from east to west, one proceeds from New York City, through the border of Ohio and West Virginia, upwards through Illinois and across the Great Plains, edging Wyoming in favor of Montana, and, after cutting through the stovepipe tip of Idaho, ends up at the Pacific Coast of Washington.

The rest of the page consists of a series of placenames and dates, beginning with “Home, NYC, New York / George Washington Bridge / Morristown, NJ / Easton, Pennsylvania — Spring 1983” and ending with “Thru Cathlamet, Washington / South over Columbia River /West on Rt. 30 thru. Astoria, Warrenton / Hammond, Ft. Stevens Park / The South Jetty, The Pacific Ocean — September 26 to September 29, 1997.”

Because of the complete lack of context for both the map and the coordinates that follow it, understanding the full picture takes a while. Art Garfunkel walked across the United States, you realize, eventually. And it took him roughly twelve years to do it.

Why did Art Garfunkel walk across the United States? The only clue is a small link at the top of the page, entitled “Quotes About the Walk.” “Somewhere around ’84,” Garfunkel explains in the following page, “I left my New York apartment, cut across Central Park, and went past my alma mater Columbia University, across the George Washington Bridge and I was in New Jersey. Most of the time I was alone with my Sony Walkman and my notebook in my pocket… Over forty more excursions, about three a year, taking about twelve years, I crossed the entire United States.”

“Quotes About the Walk” also includes selections from a Sports Illustrated article written by Tom Dunkel, which describes Garfunkel’s method more fully: “The Walk is conducted in pick-up-where-you-left-off spurts of approximately one week and 100 miles. Every four months or so, Art flies from his Manhattan apartment and continues his walk through the back roads of America.”

Not only is the walk non-continuous, but less arduous than you might expect. “Early on,” Dunkel writes, “Garfunkel would either hitch hike or double back on foot to the nearest motel every night. However, somewhere in West Virginia it occurred to him that all those wasted hours might add up to an extra decade on the road. Now… he travels “rich man style,” with an assistant to drive him to that day’s starting point, scout lunch, and room accommodations, run errands and retrieve him at the end of the day.”

A far cry from Basho, maybe, but Garfunkel still manages to wax lyrical. “[J]ust follow your sense of direction,” he writes, “and cut through the earth as if you were two years old and an unprogrammed human being who is going to just go, you know, that verb ‘to go’ and you see the hills that are twelve miles away, and you say ‘I’m going there,’ and you walk there!”

“Walk Across America” is so thoroughly odd and so precisely documented that it transcends mere existence; it convinces us beyond a doubt that at some point Art Garfunkel was here. But the question remains: why this form? Why, having walked across America — in short spurts, over a period of roughly twelve years, with an assistant — did Art Garfunkel decide to present this journey as a poorly-rendered map of America with a single line running through it and a seemingly unremarkable series of dates and places?

The answer, I think, is twofold. The first answer is that Art Garfunkel lacks the ability to present his experiences in any other way. The second answer is that, increasingly, people are presenting their lives in the same way Art Garfunkel does: in random bursts of information, free of context, and that these bursts are what we consider personhood in the digital sphere.

“You see the hills that are twelve miles away, and you say ‘I’m going there,’ and you walk there!” Obviously, Art Garfunkel is not very good at rendering his lived experience through language.

Not that he didn’t try. During the twelve-odd years of his Walk he gave interviews — with Sports Illustrated, quoted above, among others — and when more interviews were not forthcoming he had himself interviewed for his collection of “prose poems” entitled Still Water, in which he spoke about the Walk as a project of reclamation, or even mourning: “The landscape seems to change with time much more rapidly than I thought. I try to look at what is no longer on earth, things that existed up until just recently.”

Is Art Garfunkel talking about the United States, or about himself? Hard to tell. What you can tell, quite easily, is that the experience itself is impossible for him put into words.

So, after it became clear that no one wanted to hear him speak publicly about his Walk — and I know this because artgarfunkel.com keeps track of every interview and article published about him since 1973 — Art Garfunkel resorted to the form he knew best. He gave a commemorative concert entitled “Across America,” featuring works from his solo career and his days with Simon and Garfunkel, which is available on CD and DVD on his website, and which have received favorable reviews on Amazon.

None of these reviews mention the Walk itself. One begins “In 1984, Art Garfunkel stated [sic] walking across the United States of America. I don’t know if this is true, but he finally finished in 1996.” Perhaps the reviewer would have felt more confident in the truth of Garfunkel’s mission if he/she had access to the map on Garfunkel’s website. Those precious few people who buy the “Across America” DVD — twenty customer reviews — are more interested in Art’s “reflective” renditions of classic songs than his attempts “to look at what is no longer on earth.”

Viewed objectively, all of these responses — a collection of interviews, a commemorative concert and the accompanying CD/DVD, even the quotes he includes in “Quotes About the Walk” — are failures. At best, they’re a little vague. At worst they verge on self-parody. A book of such quotes would have been totally unbearable, as his poetry shows us. (But the time has not yet come to speak of the poetry.)

So Art Garfunkel has given us the only permanent record he is capable of: a line across America and a list of dates and placenames. It might be pathetic, if it weren’t for the fact that the ensuing list has a sort of beautiful simplicity, and if it weren’t for the fact that names and dates (and occasionally, photographs) are all most of us are capable of, either.

* * *

Among a few other things, most of use the internet to document our existence. We do this partially for the benefit of our friends — “I wonder what Sam’s doing now; oh, he’s writing an article on Art Garfunkel” — and, increasingly, for the benefit of advertisers, who use this self-documentation to sell us things. New developments in the setup of Facebook, in particular, have expanded this self-documentation (or self-historicization): the Timeline feature, most notably, although the burgeoning attempts to create separate Facebook pages for the history of relationships, musical acts, and businesses are equally interesting, both for their scope and for their relative flatness.

Among a few other things, most of use the internet to document our existence. We do this partially for the benefit of our friends — “I wonder what Sam’s doing now; oh, he’s writing an article on Art Garfunkel” — and, increasingly, for the benefit of advertisers, who use this self-documentation to sell us things. New developments in the setup of Facebook, in particular, have expanded this self-documentation (or self-historicization): the Timeline feature, most notably, although the burgeoning attempts to create separate Facebook pages for the history of relationships, musical acts, and businesses are equally interesting, both for their scope and for their relative flatness.

A cursory glimpse at most people’s Timelines will show you that the level of information included doesn’t rise beyond what Garfunkel includes in his Walk map: names, places, dates, and occasional pictures of landscapes, people, and food objects. By and large, people document themselves based on accumulations of data: the songs they’ve listened to on Spotify, the books they’ve read on Goodreads, the pictures they’ve taken on Instagram, the miles they’ve run on RunTracker, the food they’ve eaten on Yumalicious or Foodspotting, the places they’ve been to with FourSquare, the businesses they’ve been to (and hated!) on Yelp, much of it filtered through the personal historical aggregator of Facebook, and used by marketers to sell us new inputs with which to express ourselves. Subsequently, we know a lot about what our friends have read, listened to, seen, and eaten, how far they’ve run, where they’ve been, but very little about what the experience of any of those things feels like.

This is not to say that people don’t sometimes provide a little context; Goodreads is one example of this. Like most social-media sites, Goodreads has both a social and a documentary function. By scrolling through your friends’ book lists – and, more importantly, their ratings and reviews – its possible to keep up a dialogue about literature through the internet, a rewarding social exchange, especially if your friends write thoughtful, voluminous reviews of books they’ve read, providing you with an insight into how their consciousnesses exist in the world, which is a rare thing.

But that isn’t how most people use Goodreads. Searching a book on Goodreads, one can immediately see that the vast majority of people on the site don’t write reviews, and even when they do, these reviews usually consist of a short, not particularly insightful defense of the rating they’ve given. Most people just provide a list of books they’ve read, along with a star rating: a simple, coherent document of their reading habits that manages to provide a great deal of information without any corresponding insight. (And Goodreads increasingly uses this information to target marketing towards you, sending you promo Q&As and targeted ads.)

Not coherence, really, but the appearance of coherence. On closer examination the difference between three stars and four, two and three, four and five, begins to look increasingly arbitrary, much as Garfunkel’s coordinates, “Frankfort, Kentucky (7 mi. W of) — October 12, 1988,” break down when you consider the airplane rides and the personal assistant, not to mention the question of where exactly one is when one is seven miles west of Frankfort, Kentucky. In a field, or a copse? In a house, with a mouse?

I am not trying to make a moral point about the internet here. I don’t know why people have decided to communicate through this exchange of basic information, whether this is because we lack the ability to explain the experiences of our lives in any other way, or else because the sharing structure has been set up in such a way that we’re encouraged to reduce our experiences to easily digestible chunks. Regardless, the fact remains that we are increasingly portraying ourselves in ways that are more about what we have done and when and where we did it than why.

* * *

This is why Art Garfunkel is such a fascinating example of Internet personhood, because Art Garfunkel, despite being a celebrity and a pseudo-creative-person, expresses himself primarily in the form of lists.

The only thing more interesting on artgarfunkel.com than “Walk Across America” is the section entitled “Library,” which consists of two sub-sections: “Book List” and “Favorite Books.” “Book List” consists, quite simply, a list of every book Art Garfunkel has read since June 1968. The first book is Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Confessions. The last recorded book is Malcom Gladwell’s Blink. For each book, Garfunkel provides the year of publication, the page count, the author, the title, and the date he read it. The only context given for the list is a short explanation at the top of the page:

Since the 1960’s, Art Garfunkel has been a voracious reader. We are pleased to present a listing of every book Art has read over the last 44 years. The book list has been divided into several pages to allow easy downloading. Each page indicates the author, title, date of publication and number of pages (when available).

As with most people’s Goodreads posts, there are no reviews, but unlike Goodreads, Art Garfunkel doesn’t even provide us with ratings. No effort is made to contextualize the reading in any kind of lived experience, which lends Garfunkel’s list a compelling kind of mystery. Why, for example, did he read decide to read Henry James’ The Ambassadors in Aug 1977, and then to immediately follow it with Stephen King’s The Shining? Why did he decide to read Cicero’s Collected Works, which he claims was published in 60 B.C., and then jump roughly two thousand years and read Elie Weisel’s The Testament? About these and all other qualitative questions, the list is totally opaque.

Except, of course, that there is a sub-list, entitled “Favorite Books,” which tells us a few things. We can tell, for example, that between The Ambassadors and The Shining, only the latter made the favorites list, although Portrait of a Lady — which, in case you were wondering, Garfunkel read in June of 1975 — gives James a place in the halls of glory. We see that Garfunkel is a fan of E.L. James, as his most contemporary favorite is Fifty Shades of Grey. In short, we can make some qualitative judgments among the glut of books Garfunkel has read in his life.

Or can we? What does a Favorites list really matter, if we don’t know why Garfunkel has decided on the books he’s chosen? I can assume, for example, that Garfunkel’s decision to put Portrait of Lady on his Favorites list but not The Ambassadors reflects his preference for James’ more conventionally realistic middle period over the verbal evasions of the late James, but my assumption says more about me than it does about Art Garfunkel. The same goes for my wild imaginings over why he chose Bukowski’s Post Office over Moby Dick — did he just not have the time for Melville’s wordiness, or is he just sort of an idiot? Did he have a hard time getting through all the parts about whaling procedures? Nobody can tell me other than Art Garfunkel, and Art Garfunkel isn’t talking.

And yet, Art Garfunkel felt compelled to compile this list, without context, and then to publish it on the internet, something which would seem weird and pathological if everybody in America (and, increasingly, the world) weren’t doing it too.

We have become a nation of inveterate list-makers. Some of these lists are produced by websites, like the Flavorpill “10 Best Authors’ Homes,” “the 10 best book for Christmas,” “the 10 albums that influenced Nevermind,” “the 100 most important living writers who live in New York City.” Some of them are personal manifestations of preference, as if people are mainly manifestations of the media they enjoy. The shelves on Goodreads are a list. Spotify playlists are a list. A Facebook timeline is a particularly variegated form of list-making, one with wider breadth but no more depth than any other.

* * *

I lied, actually. There is one part of artgarfunkel.com that is more fascinating than “Book List,” one part that is even more fascinating, in its own way, than “Walk Across America.” It exists inside the “Music” section of the site, and is entitled “Body of Work.”

“Body of Work” is, fittingly, another list, again with minimal context: just a few lines proceeding two numbered columns:

“Below is a list compiled by Art Garfunkel of his entire body of work as a solo artist from 1973–2007. These songs have been ranked by Art in order of quality of his vocal performance and overall quality of the song.”

Thus the numbers proceed, in ascending order, from #134, “Take Me Away,” which Art Garfunkel considers his worst ever song, to #1, “Bright Eyes,” which he (and, perhaps coincidentally, this writer) considers his best. No effort is made to explain these decisions.

In the process of writing this essay I’ve spent more time than I care to admit listening to YouTube clips of the songs collected in “Body of Work,” trying to ascertain the difference between, say, #15, “Skywriter,” which is a gauzy piano ballad about alienation, and #10, “99 Miles from LA,” which is a gauzy guitar ballad about having a sexual fantasy on the freeway. But the truth is that no matter how much I try, I’ll never be able to understand what the hell Art Garfunkel sees as an ordering principle for his “Body of Work,” and I have come to the conclusion that he doesn’t want me to.

This, it seems to me, is the moral of Art Garfunkel, the one that rests below his relentless quantification of his own life in songs recorded, books read, miles walked, a moral that has a great deal of relevance for our own increasingly quantified, list-based documentation of our own lives. If, for whatever reason, you cannot get across to someone what it was like to have an experience, then the next best thing is to record that experience in great detail, to render it as a list, so that even though people will never know what it was like to travel through Frankfort, Kentucky on October 12, 1988, read the Collected Works of Cicero, or why you thought your version of “Sail on a Rainbow” was better than your version of “The Kid,” they will at least wonder a little, and in the process you will become a blank, a mystery, something for them to think about as they fall asleep at night, the same way I’ve been wondering about these things for the last several weeks.

I am not here to bemoan the lack of connection between people in contemporary society. Philosophically speaking, connection between people has always been nearly impossible, and there is something honest in the fact that Art Garfunkel is acknowledging this near-impossibility, while the rest of us go on insisting that a series of quantifiable observations about our experiences in the world can make up the depiction of a life. In this way, at least, condescending to Garfunkel makes no sense; he is much more mysterious than us, and maybe a little more advanced.

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent. So said Wittgenstein, that famous skeptic about what language can communicate. There is a great deal that Art Garfunkel passes over in silence, with the notable exception of his book of “prose poems,” Still Water, the majority of which is presented on artgarfunkel.com, and a piece of which I quote below:

“Today I passed the chantecler at the Ambassade d’Angleterre atop the gate in gold. Angry like the eagle, released from barnyard play, the rude bird trips the day-break calm with torch-fire, mixing memory, brave and pathetic, with desire.”

This is not very good – not very good at all. Between this, silence, and a list, I choose the list.

Sam Allingham is a fiction writer who lives in West Philadelphia. His stories have appeared in One Story, Epoch, American Short Fiction, among others. He is now the proud owner of a Pennsylvania driver’s license.

Images by Lucy Weltner

This post may contain affiliate links.