Before I cracked open Tan Lin’s latest Heath Course Pak, I showed the book off to my 93 year-old grandfather, Mark. His hands held the spine gingerly as he leafed through some early pages. He noted “it’s a conglomeration of several different sections,” then settled on a one of them called “From USC 17 101 ‘Definitions,’” in which Lin quotes at length from the U.S. Copyright Code.

Before I cracked open Tan Lin’s latest Heath Course Pak, I showed the book off to my 93 year-old grandfather, Mark. His hands held the spine gingerly as he leafed through some early pages. He noted “it’s a conglomeration of several different sections,” then settled on a one of them called “From USC 17 101 ‘Definitions,’” in which Lin quotes at length from the U.S. Copyright Code.

“A “derivative work,”” Mark read aloud, “is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version…” Or a parent, I thought, or grandparent, whose derivatives manifest related DNA, and represent the sum of all previous genetic alterations to that code. Mark was still reading, “…sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form. Does this Tan Lin live in the United States?”

“I think so,” I said. “I think he teaches English in New Jersey. What do you make of the book?”

“It’s different pieces,” Mark said. We were standing in his tiny kitchen, listening to “Mr. Tambourine Man” and eating Kosher dill pickles. He looked confused, “This book is not a single story. Where did you get it?” he asked. “Are you going to read it?”

I explained that after a brief email exchange with a Counterpath Press editor—who had apparently taken note of a piece I wrote on Lin’s previous work—Heath Course Pak arrived via snail mail. I had not yet read it, but I would eventually, and while doing so find that in it Lin has written, “Most labor today is mediated via SMS or search engine”— much the same for email, as was the case with the editor and me. Lin has also written, “an attention span produces things that interest us and not the other way around,” suggesting that if I could today travel back in time and re-receive the book, I might better understand my previously latent interest in it. Which is all to say that, in lieu of time-travel—and even though this is totally obvious, it’s what I told my grandfather—I would have to actually read the book to discover what had been written inside.

But Heath Course Pak (henceforth HCP) turns out to be a tough read, in part because Tan Lin has chosen to write a book for, and about, the very attention span that doesn’t want to read it: that unique awareness, which evolved on the eve of Y2K, when two thousand years shrank to three simple characters; the distracted mind. For a reader looking forward to familiar reading territory—aka, any semblance of pulp—Lin’s explorations might not seem tasty. HCP’s meat is engineered from dumpstered text that is, like fat, the very stuff we’ve been conditioned to avoid paying attention to: post-it notes, a legal disclaimer from Project Gutenberg’s, the blogosphere’s coverage of Heath Ledger’s death, and the eText preface to The Diary of Samuel Pepys.

Certainly not the usual subway fare. Or is it? When I am without a book on the train, I’m often bored enough to take in a J Crew ad on one of those scratched panels that presumably hide some wires just under the car’s ceiling. HCP offers the chance to read a J Crew ad reprinted in a book all the while seated underneath one of those panels. And while the ad on the train feels intrusive, the ad in text offers that intruded upon reality as a literary experience; The World of Words We Don’t Want, an interesting-if-nightmarish scenario.

* * * *

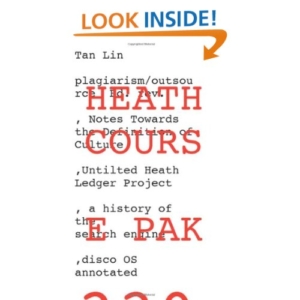

After my copy of the book had arrived, it sat in a manilla mailer on top of my white desk. For several weeks, I carried it back and forth between my house and a coffee shop, until one day when I used a “clean spoon” from the milk counter to break the postal seal. The incipit read “inexhaustible search horizon”—that’s just how I felt! I looked at the book’s cover, which, as I was to later read inside the book, Lin had designed himself using Microsoft Word. HEATH COURSE PAK is written in red courier font and overlays five subtitles written in black courier font:

plagiarism/outsource Ed. rev.;

Notes Towards the Definition of Culture;

Untitled Heath Ledger Project;

a history of the search engine;

disco OS annotated.

The resulting squash of text is confusing. In the background, no particular words fall into focus, to the effect of an apparent dimensionality. A quick glance suggests that some meaning might be buried in the otherwise chaotic jumble but that trying to concentrate on said meaning might in fact prevent its emergence. What I mean is that the cover appears like a Magic Eye pattern, in which it is only after your eyes diverge that you, the reader, are able to perceive a cryptic 3D message. According to the Wikipedia entry on such “autostereograms,” this perceptual divergence is exactly what the human brain needs in order to “see” a three dimensional scene inside a two dimensional image.

In the fluorescent coffee-shop light, I watched two women who were looking at Gawker. A bald guy in the corner was thumbing through Nabokov on a Nook. I peered over his shoulder. I peeled off the postage that, having been adhered to the package just millimeters outside HCP’s binding, had compensated the book’s delivery to my doorstep. On one of the stamps, a photograph of an earring accompanied the words “Navajo Jewelry.” The next showed a Purple Heart medal circumscribing a man’s head in profile, and read “Forever USA.” The final stamp depicted Lee Lawrie’s “Wisdom” statue; in real life, the art-deco sculpture stands in Rockefeller Center bearing the slogan “Wisdom and Knowledge shall be the stability of thy times…” I looked back at Lin’s book and realized that, since its arrival, I had mistaken the title’s first word as “H-e-a-l-t-h.” “I’m reading Health Course Pak, I’d told my sister. More accurately, I’d left the book in an envelope, and then mis-read its cover.

I felt better about all this after I started to read HCP and found, inside the book, that reading HCP is, according to Lin, “not supposed to feel like reading at all, maybe more like participatory skimming/recording,” or like “looking at someone else reading”—that’s just how I felt! So reading is a form of paying attention, producing things that interest us, and not the other way around. “I mean, basically, one wants one’s feelings distributed,” Tan Lin says. “But only someone who has feelings of their own would know what it means to have a distributed feeling. T.S. Eliot said that.”

In last May’s London Book Review, the critic Stephen Burt asks “Must poets write?” in his review of Tan Lin’s paperback Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004, The Joy of Cooking: [Airport Novel Musical Poem Painting Film Photo Hallucination Landscape].

HCP seems to ask “Must readers read?” or “What must readers read?” and, to that effect, Lin has included email transcripts, even one in which an interviewer quotes Tan Lin: “Tan sez: “One has experiences as one reads but what is the nature of those experiences?” The pages of this book open out to The World of Words We Don’t Want, which, when blended together with the real world, turns out to be a fertile “textual environment” (Lin’s words) where Lin has poeticized our experience with common language. The technique is exemplified in the following haiku-ish excerpt wherein several words are used to exemplify themselves:

i.e. a future,

i.e. pollen,

i.e. a ceiling that could labor.

“A future” here, like the past, is always real yet never available, a presence and simultaneous absence. When we read “a future,” a three-dimensional space/time idea emerges out of a flat paper page, in much the same way that HCP’s title pops out of the messy text behind it.

Stephen Burt champions such “uncreative writing” and, in doing so, cribs that descriptor from another poet, Kenneth Goldsmith. And much like both of these authors, Lin helicopters around the idea of authorship itself, observing that “as the price of originality has gone way down (everyone an artist), the price of plagiarism has sky-rocketed.” Or, as Bob Dylan once said, “Some of the people can be half right part of the time, Half of the people can be part right part of the time, But all of the people can’t be all right all of the time. T. S. Eliot said that!”

“I think emendation and quotation are varieties of writing, each linked to disparate kinds of authors or author function.” Tan Lin said that. So it’s not a shock when he, towards the end of the HCP, itself a revision of another Tan Lin book, from 2007, HEATH (plagiarism/outsource), reports having transcribed the entirety of Michael Haneke’s Funny Games “without pausing to correct typos.” Did he actually do this? Or did he simply write about having done it? Must readers read Lin’s transcription?

Lin’s Funny Games is a kind of derivative work: an actual movie script confined in its reduction to a hyper abbreviated redux, much like an adjectival “future” focused in its linguistic derivative, “a future,” and, for that matter, a book that has been approximated in its review. All of which reminds me that a grandchild is, sometimes, a chip off the old block. That, in the past, while standing in my grandfather’s kitchen, having not yet read Heath Course Pak, nor even having realized that it was not called Health Course Pak, my grandfather said “This book is going to be hard to review.” He then looked away from the cover, his eyes focused on the pickle jar, and he began to read the label.

Peter Nowogrodzki is a writer living in western New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.