In a poem by David Shapiro titled “Gold and Cardboard,” a young child asks his father ‘are there words for everything?’ The father, to clarify, asks ‘You mean the space / between // The clouds?’ The child cries, ‘Yes!’ The father, ‘No!’ And the reader feels the weight of what this means. There are not words for everything. For writers this, of course, is great news. The very next line of the poem explains why this is so, when Shapiro says ‘Like those who love to think one word will take care of Maupassant’s tree and his landlady.’

These unutterable gaps are one of the aspects of language that Wittgenstein focused on in his philosophy. Wittgenstein fancied himself something of a poet. His Tractatus was meant to be a philosophical treatise of literary proportions, a poem of philosophy, not to be confused with a philosophy of poetics; Wittgenstein was not attempting to tackle poetry with philosophy, it was quite the other way round. In 1917 Paul Engelmann, a recently made friend of Wittgenstein, sent him a poem that expresses what Shapiro’s poem hints at.

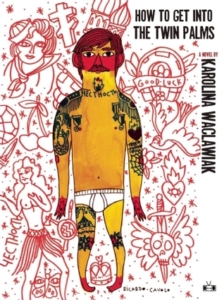

The poem, by Ludwig Uhland, is titled “Count Eberhard’s Hawthorn,” and in it, a soldier, while fighting in the Crusades, cuts a branch from a hawthorn and, upon his safe return, plants it in his yard. The branch grows into a tree and, after the soldier has become an old man, underneath it he sits “in reverie.” After reading the poem Wittgenstein writes back enthusiastically, saying “And this is how it is: if only you do not try to utter what is unutterable then nothing gets lost.” And this is how it is in certain novels: even with so many words at one’s disposal, there are still moments, spaces between, that one would lose something in an attempt to explain them. And this is how it is with Karolina Waclawiak’s debut novel How to Get Into the Twin Palms. A book trying to say something that cannot be said directly. A book so full of spaces between clouds.

The plot of How to Get Into the Twin Palms is straightforward. There is a woman who was born in Poland but moved to the States before experiencing her formative years. This makes her neither truly American nor truly Polish. Her name is Zoshya. She lives alone in Los Angeles. She is jobless. For a dab of irony, her last job was at a temp agency where she placed other people in various jobs. She lives in a nondescript apartment building across from a Russian night club called the Twin Palms, where Russian men and their wives or mistresses congregate each night to (if one can consider it a verb) Russian. Zoshya wants in.

In order to accomplish this goal, Zoshya has decided to try passing as Russian. The reader knows she speaks no Russian. And, like anyone who has ever tried to fake anything that would require fluency in a language other than their own, finds out very quickly that language is the ultimate gatekeeper into any culture. In other words, what Zoshya is attempting is impossible. And for going after that in-between that bedevils Shapiro and Wittgenstein, the same could be said of Waclaviak.

The novel consists of many short, unnumbered chapters, the first three of which form a thematic structure that mimics in miniature the structure of the entire novel. In the first, she states the aforementioned desire. In the second, she watches as a Russian man and a Russian woman, both from the Twin Palms, have sex in the night club’s parking lot. In the third, she searches a book full of Russian baby names to rechristen herself with one and to be reborn as a Russian woman at its close. Desire, sex, conception, and birth serve brilliantly as platforms on which Waclawiak is able to stand and utter the unutterable while losing very little.

How to Get Into the Twin Palms is full of spaces. For instance, in a short flashback, Zoshya tells of a visit to a Polish church to mourn the loss of Pope John Paul when she “was a child. Still learning Polish. Still learning English.” Here Zoshya is between languages. She is being filled with them from two very different sides, but language is not like a liquid — it does not take the shape of its container. There must be gaps, here and there, between her Polishness and her Americanness.

Further in, when talking about the job she lost she says that to work she “wore collared shirts to cover [her] neck, as to not appear sexual or feminine.” This type of androgyny is safe in the work place. Exist in the gap between male and female as best one can, it says, and problems at the office will dwindle, proving, of course how toxic an office environment can be.

Eventually, Zoshya does meet one of the Russian men from across the street, and they fall into an affair that constitutes a rather large section of the plot and offers up many of its own spaces between. She has chosen, in her Russian rebirth, the name Anya, but the man, Lev, insists on calling her Anka, “The diminutive, the child tense.” In this case he’s putting her in the gap. By infantilizing her, he can control the relationship, and by having sex with her, he can have her as a woman while treating her as a child, making her, what, a toy?

Later, Anya fantasizes, if one can call it that, about having sex with Lev and wonders, “if Lev would mind if I was still or if he’d want me to act like I liked it.” In this case it isn’t exactly a gap that exists, but the presence of a desire for one that isn’t there. What’s the middle ground between acting like one enjoys sex and acting like one is indifferent but knows it’s what the other wants? When Anya and Lev finally do consummate their affair, one of the more beautiful gaps is opened up and Waclawiak’s simple prose does its work so well when she writes about the moments after, when she is at a loss as to what to do:

I could hear him snoring lightly and felt that our fucking didn’t warrant a nap. It wasn’t hours. Or even half an hour. It was more like 20 minutes. The kind of sex where you hurriedly put your underwear back on…made sure you were posing so that the dimples on the side of your thigh were not visible and your breasts looked high and perky, not flat like pancakes. But he wasn’t behaving like that. He wasn’t tugging on his underwear. He wasn’t looking at me. He was asleep in my bed and I wondered how long he would stay there. I didn’t have the right to touch his back or get in close to him or coax him into letting me into his arms. We were strangers.

There are plenty of words that mean sex, but most of them only describe the intensity or willingness of the act. Quickie would probably come the closest to describing what occurred above — they certainly didn’t “make love” — but it is not quite close enough. What, then, have they done? How is Zoshya/Anya supposed to be with this man asleep next to her?

What keeps all of these stranger-in-a-strange-land moments from feeling oppressive to the reader is the exact same thing that makes the novel work so well as a whole: they aren’t immigrant-centric. Most of these little gaps apply to anyone. We can all identify with the desire to belong, the envy we feel when we find someone else’s loneliness more attractive than our own, the tension we feel from living in a world that is constantly trying to pigeon-hole us.

“I don’t want to be anything at all,” Anya/Zoshya says, summing up one of the main problems of living as a human in a fractured world. It’s all here, something for everyone. And what it comes down to, as a wildfire, another set-piece of the novel, rages across the hills of Los Angeles, is that our effort to destroy this and build that in the hopes of creating a world worth living in, a skin that is comfortable and fits properly over our skeleton, requires far too much energy, far too much heat, and in turn it scorches the Earth, leaving us standing in the center of a barren landscape feeling barren inside, looking to the left at one way to exist and looking to the right at the other and wanting to not “be anything at all,” wanting to exist in the gap between them.

This post may contain affiliate links.