In the waning years of Soviet Ukraine, on the 6th floor of a typically gloomy apartment building, an old woman is stabbed “one, twice, thrice” by teenaged Nicky Nikolai Neschastlivyi. On the floor below an infant Olga is “lying in [her] crib like an egg yolk,” seemingly disconnected from the murder aside from the geometry of neighborly life. Jump forward 20 years and we find Olga in Milwaukee, in a much more congenial apartment situation, living with Angelina, her angel of a girlfriend. One night her phone rings and she is greeted with “Privet,” an ominous hello from her past, from Nicky Nicolai who is now in America – “paying my dues,” “I’m going to Hell, Olga,” “To get to Hell they take you through America.”

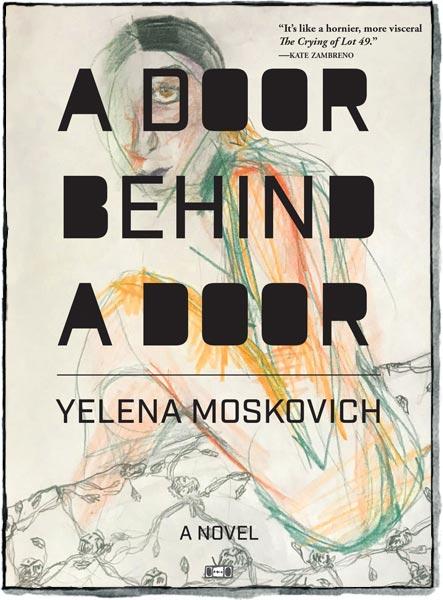

A Door Behind a Door is Yelena Moskovich’s third novel, her contribution to a venerable literary tradition of exploring Hell, with its telescoping time and scrambled geography, its thick atmosphere of mystery and violence – you are not off thinking about the world of David Lynch. It is a highly addictive book, unfolding in poetic little bursts that take up and stretch noirish crime fiction, the Russian literary inheritance, and surrealism.

I spoke with Moskovich, who like Olga immigrated to Wisconsin from Soviet Ukraine in the early 90s, but who now lives in Paris. We discussed her background in theater and how it so expertly helps her set a mood, how every Russian novel is a crime novel, and how experimental fiction can bring a sense of lightness to the reader.

Michael Schapira: I want to start by sharing my enthusiasm for the book. Did you teach this past semester?

Yelena Moskovich: Yes, I did.

Online?

Actually, the last handful of classes I had in person. A couple classes in the fall were in person, then it was online, online, and then we returned to in person.

I had the worst of all worlds with this split scenario of having some students online and some physically in the classroom.

I had a bit of that last year. Luckily I had the grace of everything being new, but that’ really difficult.

This is preamble to saying that my spirts were really low and my attention was shot at the end of the semester, so the book was genuinely therapeutic for me. I sat down and read it in one sitting, which was great because I haven’t been able to concentrate in a while.

Same with the attention. I’m kind of dyslexic and in general a slow reader, so I think that probably informs the format. Everything that I write has a lot of breathing room, so I kind of write for the shellshocked reader – probably at all times, not just post-pandemic.

That’s one thing I wanted to ask about. When you are writing you probably don’t have a specific reader in mind that you are trying to please. But there was an experience, a kind of event, of reading this book that was different, and I’m wondering whether that was something that’s in your mind or part of your thinking when you are writing a book like this. That you want some sort of experience to be happening.

Absolutely. I think it’s maybe because my background is in theater. I didn’t even really read lots of novels and prose for a while, I was only reading theater and poetry. Even in theater I was more interested in dance theater and things that aren’t the traditional you write the text and give it to the actors, but really more a collaborative body exploration. I feel like I have a similar approach to novels. There is something so personal and intimate and hallucinatory about novels because you are just sitting still, staring at words, and yet traveling in all dimensions. You have that of course in every form of art, but when it’s communal like theater or cinema you are kind of in communion with other objects, other things. It’s a very inside/out experience.

I’ve always been curious why we have this novel format that is so structured and so linear for an experience that is anything but. It’s something that is so multi-dimensional. So, it’s not so much, “oh, I wanted to do something different and new.” I keep trying to actually find the origins of travelling through storytelling and texts. It’s not necessarily going very far, but closer and closer to the root of something.

It has this rhythm to it, which hooked me immediately. There is this kind of chorus with the bolded titles and the text below. How do you manage that when you are doing readings? Is it meant to be read in a straightforward, linear way when you are reading it out loud?

I just started having a couple online events, but readings are so different when they are online. You are just reading to nobody, and I’m in a different time zone, so I’m reading to no one in the late evening while listeners are listening in the afternoon. I feel like there aren’t that many ways to read the text – I’m not sure if you’ve tried different ways of reading it out loud. When I was setting about choosing what I wanted to read I’d go through it once and listen to it and ask, okay how does that feel? The text really has its own way that it wants to be read when it is on the page. I think it actually reads how it looks, and that’s why when you are reading it I hope it has that more vocal texture.

Another thing that hooked me was the setting. I spent a month randomly housesitting for someone in Milwaukee and found it to be a very bizarre city. To have this be the backdrop for a noir, Lynchean story make a lot of sense to me. Could you speak a little more about the mood and atmosphere of Milwaukee and its surrounding suburbs?

I think it’s got this small town, very insular stuck-in-time, but also timeless quality. I really like atmospheres or moments that feel unhinged from time or from history, and yet are so informed by history, because obviously here you have this intersection of multiple cultures. Especially for someone that’s straddling this Americana versus Slavic/Eastern European inheritance.

There’s something in that experience of being nowhere, and to want to be somewhere so important all at once. What I’m saying is quite vague, but the way that I can describe it is when you are a teen and you grow up in a small city you feel like you are nowhere, you don’t matter and feel so insignificant. And yet there is a reason why teens still move on and go somewhere and have some sort of ambition beyond their small city. You have this feeling, “but I must be an important star in the sky.” So you have this simultaneous “I am no one. I’m so insignificant. Where I am doesn’t exist. I don’t exist.” And at the same time, “I must be quintessential in some way. What is it? What is the mystery? I need to find out.” I feel like a small town is that feeling, that romantic dreaminess and that deep angst — why was I put here?

That question has a dual sense for you because of your immigrant, diasporic experience where you could have ended up in many places, but you end up in Wisconsin. There were two aspects of the immigrant experience that I found really interesting in the book. For the Soviet diaspora there is this cultural inheritance that is really present in the writing – like the Lermontov poem that any Soviet child would learn or little Russian phrases that one would pick up. But there is also this inheritance, I don’t know how best to say it, of crime and this capacity for violence. Olga is just a baby when this murder happens, but somehow she has incurred some sort of debt. This is a general question, but what aspects of this diasporic experience were you able to explore in this narrative?

I like that you use the word debt, because that maybe ties into the question before and that feeling of “why am I here?” That’s a feeling that all immigrants feel, but more generally that’s the bruise of being alive. Every day I’m like, why am I born? Maybe during confinement more and more people got to feel their existential bruises. When we have a lot of distractions we’re not as connected to that question.

When you’ve been displaced, or when your origins have been fragmented or dislocated in some way, which is the case with the diaspora experience, you have this fragmentation. I’m losing myself because I’m thinking about fragmentation, but this question was about something different in the diaspora experience.

There were two things. The cultural inheritance that Soviet diasporic writers work through in various ways, and then this other, noirish inheritance.

Ah yes, the crime! I was going into fragmentation, which goes back to that original thinking about format. There’s a fragmentary sense of living, and that’s almost renewed every day. You’re breaking your own sense of fluidity by asking why am I here? By putting in question the thing that shouldn’t be put in question. Why do I have another breath? You’re going against mother nature, but that has already happened when you have been taken out of your mother land, or already had a disruption with mother nature.

For me there is a parallel between that fragmentation and crime. I even wrote an essay about how all of Russian literature is in a sense a crime novel. I love stories where people go to hell, and obviously this novel is my contribution to that literature.

Dislocation or fragmentation is a type of violence that you don’t have anything to show for. In a sense people that have lived a trauma like that, where they don’t necessarily have concrete wounds or even a concrete narrative that they can even seed to understand why they feel the way they feel – crime or a detective narrative is a way to manifest that sort of existential pain. I think that’s why for me, all these actual physicalized forms of violence like the stabbings are concrete, geographical ways of trying to figure of what is bad, what is good, the criminal, the innocent, all that stuff. I feel like that’s sort of a way to make something concrete and visible and somewhat real, of the thing inside you that feels so present, but so not real.

There’s that moment in the Nicky, Nicky, Nikolai section where he’s being roughed up by the kids outside and he can’t really locate the slap at some point, it’s just there.

He says that he can’t understand why people are so obsessed with who gets hit and who’s the smack. We’re both that contact.

Another aspect of the Sovietness is the title. My wife lived in one of those big apartment buildings in Moscow and it had the door behind the door, so that’s what I thought before reading. But in the novel the door behind the door is a trap door that leads to hell via America. Was the title referencing these Soviet apartments, or was it just a metaphysical way into the space of the novel?

I didn’t even think about that double door infrastructure. For me it was definitely that pure symbolic, metaphysical door behind a door. I also love that it is so literal in its symbolism. A door. A hallway. These are all such literal symbols, and I really love playing with literal symbols, the same way that I love playing with tropes or stereotypes.

The novel is very moody. I was listening to the Spotify playlist that you put together for it. Do you have certain things like a piece of music that help you write towards a mood? Your work gets compared to David Lynch and if you think about that Badalamenti score in Twin Peaks it’s hard to imagine writing the show without that score being there. Do you have something similar in mind when you are trying to set an atmosphere?

Definitely. Maybe it’s not so much music right away. Before I write, or in the very early stages I have a pretty keen sense of the mood, meaning the emotional texture that I am playing around with. And the lighting. Usually in my novels, whether it is day or night, there is a concrete feeling of one set of lighting happening that whole time. That baseline of light, even if it doesn’t correspond correctly with the time of day, is really important. The music comes more as I’m writing. I usually have one or two songs that I get stuck on and I like having that repetitive thing, to have something as a motor in the background.

The diner is a such a good setting for that lighting.

That fluorescent, nowhere, almost airport lighting. The complete artificiality, you don’t know where you are or what time of day it is.

It’s a kind of metaphysical novel, and there is a real exploration of time and space. I teach philosophy so this is maybe just my issue, but the book also reminded me of phenomenologists and their explorations of the body and space. Are you using these novels and playing around with the form to explore some of these philosophical questions?

One thing I inherited, despite myself, from Russian literature is that there is no such thing as entertainment or art that is not philosophical. We’re always asking a primordial question, no matter if it’s a detective story or a romance. I think about Tarkovsky, though I’m not saying my book is like his films, unless you were to play them at double speed. I love the way there are these moments that are so boring, but all of a sudden, this space opens up and it’s just sublime. You transcend your own quotidian cerebral way of understanding your day and the world and yourself and all of a sudden you are in this bigger realm of understanding, this duality of your personal, anecdotal life and this more eternal truth – which is the philosophical space. So maybe if it’s not this Tarkovskian space, I hope and try to stretch that feeling of the self and awareness to enter a more philosophical space. You have something anecdotal, which is the story that is happening. On the one hand it matters so, so much, and also not at all. Kind of like our lives.

Vaska the dog made me think of Tarkovsky. The characters are so rich in this novel. Rereading it this morning Tanya really stands out as a jolt of energy. Do you find yourself, when you have a character like that, wanting to write more in their voice despite yourself?

Tanya is very addictive. She is my bit of Sarah Kane coming through. She’s a very delicious character. Her anger is so fresh and so liberating. For me, as a writer, I really could have gone on and on. I had more that I had to slim down, because in the composition of the whole piece things have to balance themselves out. Of all the characters, that was the one that I had to reel myself in and understand that this had to be a dose in the bigger scheme. I can’t just run off with Tanya.

This might be a dumb question, but given how much this book is close to your own biography, is there any hesitancy in writing a character like Olga, who one can reasonably read as a proxy for your own experience?

No. It’s funny, I feel like the three novels I’ve written are not about me because they are more in this surreal space that is not directly recognizable as something I’m living. And yet, characters are often immigrants. In this one she really has a very similar immigration timeline as me. I think it’s kind of interesting to have such a direct doppelgänger, because when they are so precise it becomes just as fictional. For example, I was playing around a while ago with this other thing I never went with, but writing a novel about a Yelena. I was really using very specific identical facts about me, but having her do things that I’ve never done, but a reader would never know that. They would see my name on the cover and assume certain things. I was interested in pushing the limits of that, how much would you believe that I would do? But I think that’s more of a performance art idea.

To be honest I didn’t feel that exposed by Olga. There are certain things like the timeline that she has in common with me. Otherwise, I still think that it’s quite coded. A person reading this could say, “you too came from the Soviet Union at this time,” but that’s just a fact, just a bio available on the book cover. It’s not the same as someone writing about their specific experience, their specific mother, so I didn’t feel that exposed.

I have another biographical question that maybe is or isn’t interesting, but you’ve lived in France for a little while now. If you grow up speaking Russian as your mother tongue and learn English a little later, does adding a third language do something for you in your writing?

I’ve been here now for 14 years, the majority of my adult life. There are two things. When I came to America that wasn’t my choice, I was seven. I was part of somebody else’s immigration story, so I felt that moving to France, becoming a citizen, figuring everything out, sometimes being really overwhelmed and calling my parents and them saying, well, this is what immigration is. Imagine having two kids. Tough love, Slavic parents.

Part of language acquisition is not just the language that you speak, but the journey that you took to acquire that language. Within the language, within me speaking French or having French as part of my linguistic expression is the experience of how I learned it, which was very much an experience of immigration, my own immigration that was finally chosen. In a sense I had to reenact the original immigration trauma to heal something. That’s why the French language is very special for me. It’s this third, this other language this is mine, that no one made me learn, or that I didn’t have to learn for practical reasons. It’s a language where I’m a complete foreigner, and therefore feel quite at home. In Russian, because we were Jewish we were never really considered as having the same native status. But in France, of course I’m a foreigner. I have no roots, so finally I can make it my own. I have no obligations. It’s kind of a clean slate. There is a certain space that it opened up for me on an emotional level, to have this language.

My parents only speak Russian to me, and I usually speak a mixture back. Here most of my friends and people around me are from everywhere, so we’re always speaking a whole bunch of languages. French, French, French, a couple of words in Spanish that I know, oh wait a second, this friend doesn’t speak French, so English, English, English. I feel very at home in that malleability. I would be most at ease if I could just speak and switch languages as the words come to me.

I lived in France for a year and when I arrived, they described the paperwork and bureaucracy as Sovietique, so maybe that helps to feel at home.

It’s true, the administration here is tremendously slow.

The way you were describing Paris, it has a resonance in the history of the Russian artistic diaspora community. Cities have changed a lot in the past few decades. Do you still find some of that old diasporic experience alive in Paris?

Absolutely. I think maybe now it’s more akin to cosmopolitan cities that serve as a crossroads for these emotional vagabonds, people that are looking for themselves or something beyond where they are from. Paris or New York or London become hubs for people that feel outside of something is happening where they are. It’s this interesting thing where you have cities made of outsiders. I think that’s something that I really love about cities, and Paris in particular, because it’s a smaller version of a city like New York or London. I feel like maybe at heart I’m a village or low-key person, but I like the cultural palate of a city, that most people are not necessarily natives of a cosmopolitan city and a lot of people have had to have their own kind of immigration story, whether it’s from a country or leaving a certain community to start over again and remake themselves. I think that absolutely still exists in Paris and these other cosmopolitan hubs.

You talk about theater and drawing inspiration from things outside of writing, noting that your own reading history may not be as extensive as some other novelists (which is probably a good thing). But there is such a visceral quality to the book. Right from the very beginning you are describing Olga as a baby giggling like an egg yolk in her crib, then there are French fries dipped in ice cream, grilled cheese dripping down one’s lips. You can really feel it all. Are there any other writers who you really admire for being able to capture that same kind of visceral, embodied experience. It’s more obvious when you are talking about physical theater and dance, but are there any novelists or poets that you admire on this front?

Yeah, a bunch. Even though I am a slow reader, I read a lot at my own pace, because I absolutely love books. There are people that are slow lovers and those that race through. There are so many books that I’d love to read but I can’t surpass my own tempo.

I really love Yoko Tawada. She’s a Japanese writer who moved to Germany and actually speaks Russian. She writes in German instead of Japanese, though there are a few novels that she wrote in both simultaneously. Her work in translated by New Directions. There is something very dangerous to her writing in the sense that it doesn’t feel like it’s contained to the page. She’s always describing these very small moments. There is one short story in her collection Where Europe Begins. If I remember correctly there are these neighbors and this woman…I think it happens in Hamburg and she’s moved from the East somewhere. She has these smiley face stickers that she puts on her computer or on the door. You can see that she’s not doing well. I still remember the texture and the gloss of these stickers. There is something so visceral about how she created this mood of someone having such a longing to belong, but not being able to belong, not being able to reach out and make friends. Everything that goes into that kind of being a bit afraid, wanting so much to integrate but being afraid to show yourself. That moment is encapsulated in the gloss of this sticker. There is so much of that in her writing. And she’s also quite lyrical in an unexpected way. She’s definitely a big influence in terms of sensory things.

Maybe one last question. Has confinement made you take any weird directions in your writing?

I finished this book during the first confinement. So maybe I’ll know with a little bit more time whether it shaped this book, because I still feel like I don’t have enough perspective. I just finished this short story collection that is not quite ready to be talked about. That’s what I was working on for the rest of the confinement. I don’t know if this is a direct impact of confinement, but I felt like I definitely wanted to explode and tear up the page, just really shake something up or find some life. I was so tired of things being dead of synthetic that I think it upped the ante for what I’m normally looking for in language. I want it to either be alive or be resurrected. It doesn’t matter if it’s dead or has died many times. When I’m reading it there has to be some sort of life. So I started definitely taking more risks with my own process and reaching a bit farther outside of my own comfort zone.

Wonderful, I can’t wait for those stories to eventually find their way out. I just want to thank you again for the book. Reading it was genuinely therapeutic and helped to recenter myself after a draining semester.

Thank you so much. I think at the end of the day when you are writing something experimental it is viewed as difficult. We think of experimental fiction as needing a lot and taking something from us. But experimental writing can have that same kind of release and can leave you feeling light and open. It can be a healing experience in the way that entertainment can be. So that comment feels very validating to hear.

Michael Schapira is an Interviews Editor at Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.