Tr. from Hebrew by Nathan Englander, Miriam Shlesinger, and Sondra Silverston

Once Upon a Time, in a Very Small Space . . .

Etgar Keret’s first collection of very short stories (and in the original Hebrew they would be even shorter) was translated into English in 2004. The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God was a hit in his homeland of Israel and became something of a cult book here in the States. That book and the five collections that followed are all, by turns, as manic as they are moving and as funny as they feel philosophically motivated and morally complex.

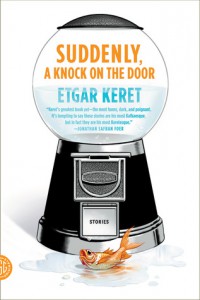

Keret’s latest story collection, Suddenly, a Knock on the Door, is not only his best book thus far but his most cohesive statement yet. It is an anxious collection, book-ended by tales about writers having to perform and tell stories on demand. The collection opens with the title story, about a writer named Keret who must tell a story at gunpoint. The armed stranger warns Keret: “It’s either a story or a bullet between the eyes.”

Keret’s stories often seem fueled by some kinetic narrative germ: he lets something loose upon the world and then does his best to keep up. The stories in Suddenly, a Knock on the Door are characterized by a tone so artfully casual yet distressed it sometimes feels we are in the presence of a narrator who can hardly catch his breath. Keret’s best characters chase something, and they often have no idea what it is. The same goes for his readers, who are usually left feeling disoriented from the experience, as if awaking from some dream. This can at times be frustrating, but it really is a result of our expectations regarding what a story “should” do. Dreams invite but resist interpretation, and Keret at his best, like Kafka, does the same.

In “Shut,” Haggai fantasizes all the time — to the point of danger. He constantly imagines having something else or someone else, even while he’s driving with his eyes closed. It is a tense and nerve-wracking three pages, narrated by Haggai’s good friend. Or is he? Because it seems this good friend has been stealing something from Haggai all along.

In “Healthy Start,” lonely Miron, post-breakup, spends his days in a café waiting for unsuspecting individuals on the lookout for people they are planning to meet. Upon which Miron raises a hand and plays the part. As you can imagine, this leads to trouble. But it’s a trouble Miron welcomes because he makes contact.

In “Mystique,” a man sits on an airplane convinced the man beside him is saying exactly what he would be saying, should he open his mouth and speak, even as the stranger lies to his wife over the phone. Or is it all a pretense, protracted self-horror, as the man projects himself onto a stranger’s behavior? Make-believe is a repeating subject for Keret and one of the reasons why a book of disparate and fleeting portraits holds together so well. After all, what is fantasy if not a wish for something new, something else, for some “knock on the door”?

If you are familiar with Keret’s previous work, you will be pleased to know there are plenty of animals in this collection, because it would not be Keret without animals. We find a woman who gives birth to cats, a man who recognizes the soul of his murdered wife in the body of a poodle, and a talking goldfish. In that story, “What, of this Goldfish, Would You Wish?” (one of a handful notably translated by Nathan Englander), Yoni decides he will make a documentary, “no prep, no planning, natural as can be.” Which is not a bad way of describing Keret’s mode as well. But don’t be fooled: Keret’s casual and conversational tone is deliberate, carefully constructed, and peppered with spot-on metaphors.

It must be said that not all of Keret’s hits are homeruns. A few stories end on a rather pat note, leaving not much work for the reader. Which is odd (and thankfully rare) when considering that Keret’s best stories leave the reader working long after closing this book. “Guava,” for instance, is a moving and perplexing parable-like story about a man who becomes a piece of fruit. Two pages, mind you.

It is this offbeat sensibility that places Keret alongside writers like Donald Barthelme, Lydia Davis, and Jorge Luis Borges, who create whole new worlds — utterly surreal but entirely familiar — just a few pages at a time. Suddenly, a Knock on the Door is Keret’s dark, disquieting, and comically brilliant attempt at capturing the human spirit in a very, very small space.

This post may contain affiliate links.