Girlchild, by Tupelo Hassman

Girlchild, by Tupelo Hassman

[Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2012]

I read girlchild so fast it hurt. When I’d whipped through its chapters over the course of a day and arrived, suddenly, at the last page, I put my head down on the table in front of me and started to cry. Tupelo Hassman’s debut novel knocks the wind out of you.

Girlchild is the story of Rory Dawn Hendrix, a girl growing up in a trailer park in the Nevada desert: “Just north of Reno and just south of nowhere is a town full of trailers and the front doors of the dirtiest ones open onto the Calle.” In a series of short chapters, written mostly in Rory’s own words but also featuring an assortment of other materials (excerpts from social workers’ files, a 1947 copy of the Girl Scout Handbook, cocktail recipes, word problems from a math test, to name a few), we learn about Rory’s home, her mother, her grandmother and their lives in one of the most impoverished and forgotten places in the country. This is a book, largely, about poor women — Rory, her mother, and her grandmother the last three generations in a long line of poor, single mothers and their daughters – and what results from the excruciating lack of options in their lives.

Grandma didn’t start out smart, she’d say, and however many years passed she never admitted to feeling much smarter. She didn’t feel too smart when she was thirteen and pregnant, and didn’t know why or how, and had an abortion on a table in a room in the dimly lit part of San Francisco’s Tenderloin. She didn’t feel too smart when she was sick for weeks after, crawling from her bed to the toilet to relieve both ends, her mouth lined with fever blisters from the infection that came and went in a flash, just like the baby’s father.

Less than two years later, despite the scars and the lessons learned, she had another mouth to feed anyway. My mama. And then more and more, six by the time she was done and finally legal, twenty-one years old. Mama, true to tradition, found herself pregnant at age fifteen. Grandma had been too afraid to tell her daughters how babies happen, superstitious that simply saying the words would bring them into being, and so her daughters found out the same way she had.

The lives described in this book are ones that are so thoroughly marginalized — economically, sociologically, politically and culturally — that it sometimes feels as though girlchild was, in part, written to bear witness. But while the book is searing in its accounting of the effects of poverty, sexual abuse, and isolation (in many forms), in shining a spotlight on this community Hassman doesn’t just expose the devastation but also the love, humor, and warmth that can still be found there.

Girlchild is a vivid and unforgettable illumination of a young girl’s growing up on the fringes, as well as a damning indictment of the social and government programs that prove entirely useless in helping her and those she loves.

— Nika Knight, Interviews Editor

Imagine stopping in a small, non-descript town on the way between here and there. You park your car, walk into the local diner and order some eggs, and maybe then some pie (damn good pie). The drive has been long and so you decide to take a walk to stretch your legs. Wandering down the little main street, you pass a store with a cluttered window; there are piles of gold-embossed books, a globe, a skull with a map to the unconscious etched onto it. You walk in and breathe in that sweet, sweet smell of musty books that always gets you. There’s a tabby cat curled up in the one spot of sun that has penetrated this temple of the esoteric and the forgotten.

Imagine stopping in a small, non-descript town on the way between here and there. You park your car, walk into the local diner and order some eggs, and maybe then some pie (damn good pie). The drive has been long and so you decide to take a walk to stretch your legs. Wandering down the little main street, you pass a store with a cluttered window; there are piles of gold-embossed books, a globe, a skull with a map to the unconscious etched onto it. You walk in and breathe in that sweet, sweet smell of musty books that always gets you. There’s a tabby cat curled up in the one spot of sun that has penetrated this temple of the esoteric and the forgotten.

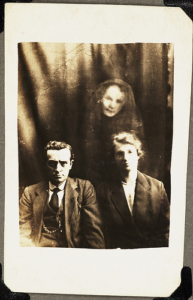

These are the kinds of experiences that I’ve been led to believe are becoming endangered in the face of that great predator known colloquially as the internet. And yet, I recently had that very same dust-and-must-filled, heart-pattering feeling—the kind you get when surrounded by old books that nobody remembers and you never knew you wanted to read–while perusing, of all places, a website. The Public Domain Review is a beautifully curated collection of unusual and obscure books, images, sounds, and movies that the editors have dug up from the backrooms of the public domain and paired with a selection of new, longform essays that focus on this oft-ignored material. Books like The Medical Aspects of Death, and the Medical Aspects of the Human Mind and Wonderful Balloon Ascents, mingle with James Joyce’s newly public-domained Chamber Music, a pre-Dubliners collection of love poems. Buster Keaton’s hilarious slapstick gem The General is free to stream, the voices of Houdini and Florence Nightingale have been revived for the occasion, and some choice picture albums have been dusted off, including one of the spirit photographs of William Hope and one of the 1970s space colony art from NASA’s Ames Research Center. And all of them are rendered as beautiful facsimiles that perhaps don’t entirely recreate the experience of handling a book, but at least your allergies won’t kick in. In any case, browsing the site resulted in one of the most exciting, book-nerdy experiences I’ve had on the internet in a long, long time.

— Jesse Miller, Reviews Editor

Two Interviews with Chris Onstad

Two Interviews with Chris Onstad

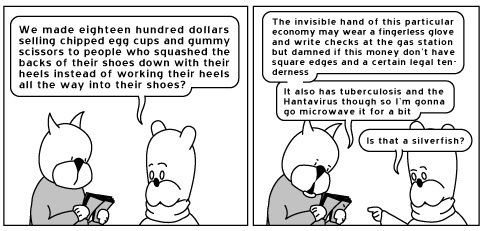

Last March, Chris Onstad announced that his much loved webcomic Achewood would be taking an indefinite hiatus. At the time no one was sure what that meant, Onstad included. In the year or so leading up to the break, the strip appeared less frequently, bummed fans either adjusted to the new schedule or stopped following but there wasn’t (as far as I could tell) much fear that Achewood was over.

Which is to say that when the other foot came down in March, I was shocked. In fact I bemoaned its loss right here on Full Stop, assuming the whole thing was a wrap. But lo and behold, in late November of last year Onstad posted a new strip. In December he dropped two.

Achewood, it seems, is back, and it’s a rough beast having some rough chuckles. So far the strips have been surreal and dark, a reminder that Onstad’s proclivity to turn weird and gruesome is an important part of the comic. They’re still funny, but it feels like Onstad is pushing his boundaries here, taking fully formed characters (talking alcoholic cats, etc.) and sending them down the rabbit hole. It’s all unfolding slowly, but I couldn’t be happier it’s back.

Graham Greene once said : “hilariously funny and of a sadness” in reference to something else (duh), but that’s Achewood to a T. Full of pathos and wiener jokes, it’s a peerless American comedy. In honor of it’s return, I’m recommending two of Onstad’s interviews (and the whole series by implication). The first, an interview with the New Yorker’s Cartoon Lounge blog, is without a doubt the funniest Q&A I’ve ever read. It’s also mostly nonsense Example:

What is your ideal day?

Onstad: Wake up, hot merguez sausages on a plate, Madeleine Peyroux posters on sale, turn off the radio, it was all a dream. Wake up.

Ideal night?

Onstad: Chris Isaak driving a fairly heavy American car on a large beach, and carving it artfully around in large swoops. Not trying to get anything done, just enjoying the physics of the event. I’m watching from a nearby home.

The second is an interview Onstad did with Comics Alliance in January in which he has a relatively sober conversation about leaving and coming back (OK, OK, it’s like the fucking temperence movement by comparison). It’s also a great discussion of the struggles that come with work on the internet and the burden of creating something that people really love. If you’re already an Achewood fan, these are a must read. If you’re not, these interviews (the first one especially) are a great place to start (an even better place to start is the Subway Wars arc). Remember, there’s no shame in jumping aboard during the second coming, just don’t wait ’til the third.

— Jesse Montgomery, Managing Editor

The Critic (1994-1995)

As I recently went through an energy-sucking, completely bullshit head cold, I took comfort in an old friend, Jay Sherman, of Fox’s short-lived but completely brilliant animated show The Critic. Starring the voice of Jon Lovitz, The Critic is a show I found hilarious as an eight-year-old, even though I didn’t get half the jokes (just like its sister show, The Simpsons). The show is quick, well-written, and completely insane. I stopped watching the offensive and boring Family Guy a couple years ago, but was kind of stunned by how badly they would execute their cut-a-way scenes. The Critic were real good at the pop-culture throwaway line (even better than The Simpsons, yeah yeah yeah). For a soothing balm, look to YouTube, where you can find most episodes of The Critic, a cartoon taken too soon from us.

— Max Rivlin-Nadler, Blog Editor

Supporting WFMU and Independent Radio

Newt Gingrich has Sheldon and Miriam Adelson. Rick Santorum has Foster Friess. If the money spigots are open this season, why shouldn’t WFMU look for their own sugar daddy? The free form radio behemoth from Jersey City kicked off their 2012 marathon on Monday with the bold call for one $1 million donation to build “a kick-ass performance space, expand our live music studio,” and make some necessary repairs on their building

But there are other options for the not-obscenely rich. If you start to poke around the different DJ Premiums that listeners can receive for donating at the $75 level, you get an idea of how weird the station is and why it’s so important to keep it going. There are t-shirts, shot glasses, a coloring book, DVDs, stickers, and CD compilations for any musical persuasion – -Japanese psych and ritual music, seventies superhits, Ragnarock inspire rarities, and “kosmigroov klassicks.” I’ll be donating during Tom Scharpling’s Best Show on WFMU (Tuesdays from 9 – midnight), which is hands down the best use of the radio medium today and the strongest argument to support the station because a show like this could not happen elsewhere. So don’t be a chump and make your way over to the donation page today.

— Michael Schapira, Series Editor (Thinking The Present)

This post may contain affiliate links.