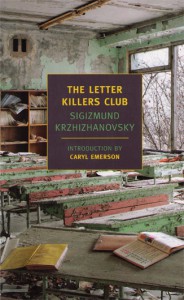

[NYRB Classics; 2012]

The Letter Killers Club, by Russian modernist Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, is built upon the concept that ideas are more than the thoughts we have. In a novel where writers are “professional word tamers” and words transitory creatures in search of freedom, the weight of an idea is worth more to Zez than books or money. Zez, the president of the Letter Killers Club, considers libraries to be destroying imagination: all written material must be destroyed to save the ideas in people’s heads. Although The Letter Killers Club was rejected for publication in 1928 for not promoting Communist values, it is not a satire of book banning or a call to arms against thought control. Despite the novel’s rather dystopian premise, the closed, highly-monitored society in which the novel is set serves mainly as a background: Krzhizhanovsky is interested in language and philosophy, not politics.

According to Zez, any idea committed to paper is committed to death. To preserve ideas in their purest form, they are spoken. And so, every Saturday Zez and six companions, called “conceivers” and referred to only by nonsense syllables, gather in a room filled with empty bookshelves as one member holds the floor to tell his “conception.” The reader is invited into this world as leader Zez brings the nameless narrator — a literal stand-in for the reader — to the Club as an observer. Thrown into this environment, the narrator is as amazed as he is puzzled, and it is hardly surprising when he learns that the dynamics of the room are not all well and that there is another reason for drawing this eighth armchair around the fire.

Krzhizhanovsky’s interest lies in words as philosophy, but the stories-within-the-novel reveal his gift as a spinner of yarns as well. The tales told in the bare room are fantastical: two Shakespearean actors journey to the Land of Roles and meet Richard Burbage, a young bride is married to an entire village in a farcical mix-up. There are games played with perspective and space, elaborate weavings through time, and character shifts. Each tale reveals a clever mind, but also reflects the inconsistencies inherent in oral narrative, when one has no written pages on which to look back. Frequently the conceiver of the evening loses his theme or ends up in an expected place by the end; Zez holds them all accountable. Their wanderings are a consideration of the writing process and Zez acts the professor, instructing the men to return to the story from a different angle or to attempt something new altogether.

Although the stories, with their twists and malleability, are enjoyable to read, the novel’s turbulence is felt most acutely in what is said outside of the stories and inside of the room. Zez is an exacting president, but not every member is as staunch in their belief that words will be free so long as they are not written in ink.

Given the societal backdrop against which Krzhizhanovsky wrote, it is not so difficult to understand the seeming-reality of his constructed world, how words could be seen to have so much weight they needed to be destroyed to be set free and ideas worth more in the minds of men than in a novel. There is a shadow to the merry tales and fables spun in an empty room that pervades even seven decades later. Krzhizhanovsky said his interests lay, “not in the arithmetic, but in the algebra of life” and he has certainly left a puzzle of ideas and freedom to be worked on by readers for decades more.

This post may contain affiliate links.