In 1939, The Partisan Review sent out a questionnaire to a number of prominent writers, asking them about literature, politics and their identities. While the questionnaire hasn’t been completely forgotten, we felt that these specifically political questions were rarely being asked of our writers. Considering that 2011 was a year of global unrest, we felt that it would be particularly relevant to update The Partisan Review’s questions. (For the curious, here are the original questions.)

In 1939, The Partisan Review sent out a questionnaire to a number of prominent writers, asking them about literature, politics and their identities. While the questionnaire hasn’t been completely forgotten, we felt that these specifically political questions were rarely being asked of our writers. Considering that 2011 was a year of global unrest, we felt that it would be particularly relevant to update The Partisan Review’s questions. (For the curious, here are the original questions.)

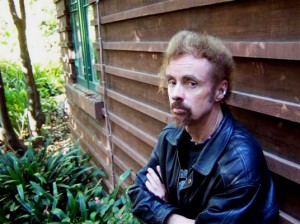

T.C. Boyle is the author of over a dozen novels. His most recent novel, When The Killing’s Done, was released last year. San Miguel, his next novel, will be published in the fall of 2012.

2011 was the year of the Arab Spring. There have also been massive protests in Greece, Spain, Britain, and most recently, the United States. Does literature have a responsibility to respond to popular upheaval

Literature has no responsibility except to itself. I write about what moves me, which often seems to revolve around environmental themes, as reflected in novels such as A Friend of the Earth and When the Killing’s Done and many of the stories in Wild Child and my other collections. I have never written about the events of 9/11, for instance, unlike Sherman Alexie or Jonathan Safran Foer or the late John Updike, whose last novel, Terrorist, explored the notion of indoctrination and Islamic fundamentalism. Events move me, just as they move other artists, but unless something speaks to me artistically, I will not pursue it. To my mind, George W. Bush, during his eight-year reign, was the single greatest enemy of America, as well as a dupe of Bin Laden, and I spoke to this repeatedly during that time, but never wrote about him and his cohort, unlike, say, Nicholson Baker. Art is a seduction, not a battering ram to score political points. There are shining exceptions, of course, in which politics and art are brilliantly wed — think of Robert Coover’s magisterial and hilarious The Public Burning.

Do you think of yourself as writing for a definite audience? If so, how would you describe this audience? Would you say that the audience for serious American writing has grown or contracted in the last ten years

I write for anyone who knows how to read, both here and abroad. From the beginning, I’ve made it a foundation of my aesthetic to try to create works that can appeal on all levels. Whether or not I’ve succeeded is not up to me to say (ask me: I’ll say yes, resoundingly), but the art I admire works in this way. I want to remind people of the essential joy of pursuing fiction for the purest of pleasure, for its subversion and recalibration of the norm, rather than as an assignment for a course or a sort of grudging intellectual duty. Has the audience for serious (read: good) fiction grown or contracted? I can’t say. But at one time I was the literary poster boy for young women, then middle-aged women, and now, appropriately, for the hardy white-haired old ladies of the world. Lord bless them. And Lord bless their male counterparts too. Lest all we have left are vampire novels and the hundred millionth reiteration of the thriller/spy novel.

Do you place much value on the criticism your work has received? For the past decade we’ve seen a series of cuts to predominant literary magazines and literary supplements, and in response, criticism has moved online. Do you think this move to the non-professional realm has made literary criticism more or less of an isolated cult?

Criticism is vitally important as it can illuminate art for a general audience and broaden the debate. Cynthia Ozick has bemoaned the death of such criticism and I have to agree with her. What has replaced it are sensationalistic, impressionistic, solipsistic and often laughably ignorant personal slings at this or that, all prejudices firmly in place. Instead of a measured and intelligent valuation, you get a sort of criticism that only seeks to draw attention to itself. (That said, I must admit that reviewers have embraced my work from the beginning and that this has made the task of sitting down to the keyboard a whole lot more amenable.) What I’d like to see more of are the sort of wide-ranging and penetrating overviews of a given writer’s work by writers and thinkers who are the equals of those they presume to analyze. This happens rarely. Why? Well, what’s in it for the critic? Is he/she going to be paid? By whom? Harper’s runs in-depth book essays, as does the New York Review of Books and other outlets. Fine and dandy. There would be more if there were more of an audience. But there isn’t.

Have you found it possible to make a living by writing the sort of thing you want to, without other work? Do you think there is a place in our current economic system and climate for literature as a profession?

I have been very fortunate and very grateful to have found an audience for my work. Fortunate too to live in a democracy in a time in which I could focus on art to the exclusion of all else. I have never written to deadline or on contract and have never listened to the pecuniary urgings of Hollywood though I have lived out here amongst film industry folk for most of my life. I’m hardcore. I do exactly as I please. And, as I say, I’ve been lucky enough to be remunerated for doing so. As for the second part of the question, I can’t say. The technological wizardry of the past twenty years has radically altered our perceptions (if there was ever any doubt, we are fully a visual society now) and squeezed our priorities so that there seems very little contemplative time left in a given day. Some years ago Bruce Springsteen wrote a song about the superabundance of channels on TV and yet having nothing worth watching. Exactly. I’d like for people to rediscover the special joy of immersion in a great story and its artistry, but I wonder how much patience the society really has. Certainly no teenage boy with access to video games (and is there a single one who doesn’t have access?) will ever read a book outside of the confines of a classroom assignment. If they’d had video games when I was a kid, I’d never have discovered writing. As it was, I barely got there.

Do you find in retrospect, that your writing reveals any allegiance to any group, class, organization, region, religion, or system of thought, or do you conceive of it as mainly the expression of yourself as an individual?

Choice B. But I will say that if you read through all twenty-two of my books (and the two coming, San Miguel, a novel, to be released in the fall 2012, and T.C Boyle Stories II, The Collected Stories, Volume II, the following fall) you will certainly know what I stand for, politically, philosophically and artistically.

How would you describe the political tendency of American writing, as a whole, since 2001? How do you feel about it yourself?

I believe I’ve addressed this in the first question. Again, for my money, politics and art make for an uneasy mix. Unless the artist is as great and sly as Arthur Miller, for instance, whose “The Crucible” stands as the one of the most satisfying and subversive examples of a beautifully integrated sociopolitical and artistic work I can think of.

Over the past ten years, America has been in a state of constant war with a nebulous enemy. This war has extended to fronts throughout the world. Have you considered the question of your opinion on an unending war on terrorism? What do you think the responsibilities of writers in general are, in the midst of unending wa

Well, since this is essentially the third iteration of the question, let me state that I never say never. I stand opposed to these wars, to corporate greed and the Party of No. But if I should create fiction in response, it would likely come at the issue indirectly—seductively, I hope — in the way that I address environmental issues and biological themes in stories like “Blinded By The Light”; “Wild Child”; “In the Zone” and so many others, or social issues in novels like The Tortilla Curtain or World’s End. We — artists, that is — seek to create microcosmic worlds, spaces in which we can control events and grow and breathe and expand aesthetically. In the end, art is art and the world is the world.

This post may contain affiliate links.