Tr. Ottilie Mulzet

by Kehan DeSousa

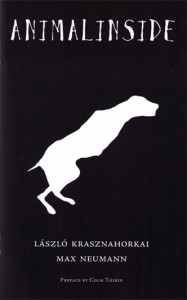

New Directions Publishing’s sleek edition of Laszlo Krasznahorkai and Max Neumann’s Animalinside resembles a paperback moleskine; it is slender, with a matte black cover and refined cream pages. Inside, the celebrated Hungarian novelist Krasznahorkai spews a hostile set of vignettes, each accompanied by visual art from German artist Max Neumann. There is a strong sense of synchrony between text and image: thirteen of the fourteen segments were illustrated after Krasznahorkai completed the text, but the first vignette, the germ of the text, drew inspiration originally from Neumann’s image of a silhouetted dog contained in a room, captured in mid-leap.

The very literal nature of the artwork clarifies and provides respite from the writing, which, while occasionally compelling, evoked no feeling of sympathy from me. The narrator—a dog, as suggested by the artwork?—seems to function as a manifestation of the reader’s id. Then again, as the vignettes progress, the narrator seems increasingly like an insane mobster direly promising violence. At times, I felt menaced by the narrator’s belligerence; at other times, I struggled to take his delusions of aggression seriously.

That, I suppose, was an intention of the text—to give voice to the tension and rage bubbling when one desires real power while trapped. I instinctively viewed this as a partial reflection of the political struggles in Hungary’s modern history, but more than that it seems like an attempted revolt against traditional literary conventions. However, despite Krasznahorkai’s unconventional tactics—repetition of blocks of text; short, dramatic conclusions to the vignettes; schizophrenic changes in narration; and a disregard for the traditional form of the sentence, among other things—the artwork remained consistently more engaging than the writing. Neumann’s visuals are deceptively simple, but even in this form possess texture and sophisticated coloring which never feel gratuitous, which cannot be said of the writing.

Colm Toibin’s preface to Animalinside praises Krasznahorkai’s craftsmanship for the demands it makes of the reader and the fierce challenge he believes it poses to writing. While the narrator does seem to oppose everything, sometimes stridently and sometimes slyly, nothing in the book strikes me as revolutionary. I finished it without finding pleasure in the rebellious writing, nor being captivated enough to devour it; as a challenge to language, at least once in translation, Animalinside proves only how impervious language is to assaults on itself.

This post may contain affiliate links.