|

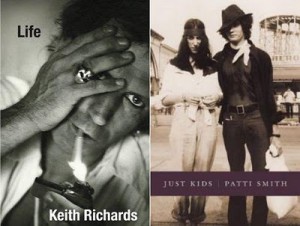

Life Keith Richards and James Fox [Little, Brown and Company; 2010] Just Kids |

by Anna-Claire Stinebring

Reading Joan Didion’s 1979 essay “The White Album” as someone born over a decade after the events it describes, I can’t help feeling like an outsider, a tourist passing through her finely wrought prose. Over the course of the essay, austerely styled to echo an era’s malaise, Didion cuts between scenes of a Black Panther’s jail cell and a Doors recording studio. It is 1966-1971, an era of rock-and-roll and militant social justice, but also of fatal overdoses and the Manson Family murders. The landscape Didion patches together from historical and personal events is meant to feel not like a series of juxtapositions, but like the feverish merging of the same insistent illogic.

As a character in her essay, Didion is always at the right place at the right time, historically speaking, but she also seems to have sleepwalked there. In “The White Album,” the goings-on of the outside world draw rapidly inwards, until they appear to merge with the author’s own mindset. She covers trials and protests without exactly giving readers her reasoning for being there, and she rents, without explanation, a twenty-eight room mansion in Hollywood for her young family, in an area an acquaintance coins as a “senseless-killing neighborhood.” She writes:

So many encounters in those years were devoid of any logic save that of the dreamwork. In the big house on Franklin Avenue many people seemed to come and go without relation to what I did. I knew where the sheets and towels were kept but I did not always know who was sleeping in every bed. I had the keys but not the key.

Even as I admire the style of Didion the writer, I can’t help wanting to shake Didion the character out of her somnambulant stupor. She seems to be watching her life in playback as it happens, as if it were already decided by some anemic, dreadful fate. That’s just a choice, some part of me wants to say to her; it’s an affect, a style. She may be living in a house that feels doomed or haunted, but at some point she actively decided to rent that crazy place to begin with.

* * *

Two new memoirs return readers to the same era as “The White Album”: Life by Keith Richards and Just Kids by Patti Smith. As stories, Richards’s Life and Smith’s Just Kids are feats of endurance and idealism, respectively. Wildly different in length and approach from “The White Album” and from each other, in all three form is shaped by persona. Richards’s Life is sprawling and cumulative, and Smith’s Just Kids, the winner of the 2010 National Book Award, is a slim but lush memoir of self-discovery through the lens of her friendship with the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

The two memoirs offer generous windows into a time period that is commonly mythologized but often remains inscrutable. Unlike Didion’s coldly detached narrator, Richards and Smith want readers to let go of the rational a little, and delight in the details of the characters and the pulse of the events. Both memoirs center around young twenty-somethings emerging into distinctive identities despite uncertain circumstances. Though Richards’s Life extends for many more decades, the core of the narrative takes place in his twenties and early thirties. Smith almost completely keeps her narrative to the time before she is famous, sensing that this restraint has the potential to magnify her story.

For my generation, the Rolling Stones have a somewhat awkward position in our collective cultural consciousness. Their music is engrained in us as if by osmosis, a song like “Street Fighting Man” inspiring a vague feeling of youth and rebellion not at all connected to the events of May of ’68, which set the stage for the song. It’s our parents’ youthful rebellion, not ours.

Same goes for punk progenitor Smith, though in high school I stumbled onto her album Horses and spent a year listening to it on repeat. Many of Smith’s lyrics were free verse-inscrutable, which intrigued me, but I was young enough that I didn’t fully understand a more straightforwardly aggressive song like “Gloria,” either. “Gloria” is her cover of a Van Morrison song by the same name, but with a decidedly provocative opening line added: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine,” Smith intones in a low, intimate voice. With all her songs, the power they conferred went beyond “getting them” fully—they seemed to draw the listener closer, part primal scream, part delicate incantation.

With Just Kids, readers have the privilege of watching Horses, Smith’s first album, grow out of innocent, unlikely beginnings. In the first chapter, Smith is an imaginative little girl in a working class family in Chicago. But Smith takes care to make readers see a unity between the forceful young woman who would write, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine” and the little girl who “would lie in my bed by the coal stove vigorously mouthing long letters to God.” See it as the inverse of “The White Album.” Like the unnerved protagonist in “The White Album,” Smith sees signs and symbols everywhere, but unlike Didion she holds to a conviction that they have a cumulative coherence.

* * *

Smith is slightly younger than Richards, and Just Kids centers around late 1960s and early 1970s New York City, when the Rolling Stones are big but before Smith begins making her own music. Along with the French writers Arthur Rimbaud and Jean Genet, it’s Jim Morrison, the Rolling Stones, and the Beat poets who loom large in the shaping of Smith’s sensibility.

A perfect moment of influence occurs in the Chelsea Hotel era of Just Kids, when Smith takes a pair of scissors and trades her Joan Baez tresses for a glam Keith Richards-inspired cut, “machete-ing my way out of the folk era.” Smith quickly gets a lot of attention for her hairdo, and Smith’s tone is rueful as she recounts it, directed at the callowness of a scene so evidently appearance-driven. Still, it’s hard to imagine Patti Smith’s portrait on the cover of her album Horses, famously shot by Mapplethorpe, without the sharp, androgynous haircut. The image captures a lean bravado that will come to define both of their styles.

Earlier in the story, we see Mapplethorpe and Smith begin their relationship as lovers, and readers already familiar with the artists’ work will know Mapplethorpe is gay. But it takes an agonizingly long time for Mapplethorpe to grow into an awareness of his homosexuality. It is a difficult realization for both young people, in part because the early romantic relationship has been so stabilizing and nurturing for both of them. While readers feel the deterioration of this genuine intimacy, it is chastening to realize that much of the crisis comes from the fact that neither has a clear model for homosexuality in the society they grew up in. “In my literary imagination, homosexuality was a poetic curse, notions I had gleaned from Mishima, Gide, and Genet,” Smith recounts, a revelation of cultural suppression and personal naiveté.

Smith relays this troubled period with great compassion for both parties. She also does something unusual: she charts the change in terms of their thinking about art as much as their personal life. While Mapplethorpe obsessively collects and arranges his new collages of saints, circus acts, and male erotica—the forerunners of his own photographic work, with its core fixation on form, sexuality, and a dichotomy of light and dark—his sense of self is also clearly in flux. Likewise, we see Smith as a young woman stalled at her own creative threshold, slowly realizing she can no longer follow the man she admires, though she attempts to for a time:

I came home and there were cutouts of statues, the torsos and buttocks of the Greeks, the Slaves of Michelangelo, images of sailors, tattoos, and stars. To keep up with him, I read Robert passages from Miracle of the Rose, but he was always a step ahead. While I was reading Genet, it was as if he was becoming Genet.

In passages like these, Smith is able to mediate adult insight and youthful bewilderment, and chart growth within her inexperience: “Where does it all lead? What will become of us? These were our young questions, and young answers were revealed.”

* * *

Just Kids has its “White Album” moments. There are scenes with fever in the air, snatches of acid-fueled jargon, heady summer days defined by that song on the radio or that murder in the news. It is a portrait of a world turning over an old order and being thrown into the unknown, but Just Kids is also a portrait of a world disappearing. Smith has an eye for rare or merely beautiful old books and therefore a tactile relationship to the words of the poems she admires. It’s hard to imagine a young Smith turning out the same if she was able to Google Rimbaud and then had to sift through the digital detritus that turned up. There is plenty of detritus lovingly described in Smith’s memoir, but these are found objects transformed into good luck charms that Mapplethorpe and Smith share. When Mapplethorpe dies of AIDS in 1989 and his possessions are auctioned off—now the elegant collection of a successful artist—they become a new way of charting loss.

Loss pervades Keith Richards’s Life, though he doesn’t always look it in the eye. As a narrator, Richards is never interested in the extended metaphors and sustained meditation that define Smith’s memoirs. But then again, why should he be? Coming in at just over 500 pages, Life’s crammed, jumbled structure neatly matches its story. Richards is a born spinner of narrative yarns, immediately addressing the reader with a frank familiarity and wily humor. The memoir is a whirlwind tour of inspiration and excess, both in musical collaboration with Rolling Stones band mates and in the solitary confinement of drug addiction. Richards sees his former heroine addiction as just one reaction to the band’s fame, and not necessarily the most destructive: “Mick chose flattery, which is very like junk — a departure from reality. I chose junk.”

In a golden period of Stones creation that includes the 1972 album Exile on Main St., Richards begins to exploit a carefully regulated cocktail of hard drugs that allows him to be a manic workaholic. Richards describes how he pragmatically, if improbably, was able to use these drugs “like gears,” at least for a time. With unflinching honesty Life also charts this ideal run ragged. By the time he pulls a record nine-day waking marathon, the energy has gone beyond inspiration into lurid entanglement, the next fix taking precedence over the music. Besides this dark period, music takes center stage, though drugs take a close second. It’s when Richards talks about the particulars of a chord or a drug that the sentences spark with a vivid precision, a tactile engagement revealing a protagonist by turns boyish nerd and knowing connoisseur, not unlike Smith with her beloved books and curios.

* * *

In Just Kids, Smith’s writing is simultaneously coiled and dreamy, reminiscent of certain lyrical yet muscled lines from her music. The memoir is compassionate and lucid as the exploration of a relationship. As an account of art-making, it is startlingly candid, detailing the simultaneous romanticism and ruthlessness that allow Smith and Mapplethorpe to originally pursue their distinctive personal styles.

In Life, part of Richards’ inimitable style is his habit of avoiding extended reflection. For another memoir this might be a serious lack, but in Life, full of jokes and sparring matches, it’s a choice that grounds the decadent particulars in a sense of restraint. “But things could have been better, baby,” is how Richards succinctly sums up the ending of his decade-long relationship with Anita Pallenberg, with whom he has two surviving children. By this point in the story, readers have absorbed the specifics of Pallenberg’s original allure and her descent into addiction-induced madness. At the fallout of the relationship, Pallenberg disconcertingly resembles the narrator of “The White Album” played out to the extreme: living in a string of derelict New York mansions, at one point she is convinced she sees “the ghosts of Mohican Indians patrolling the hilltop” in a bizarre moment of history blended with psychosis. After the blunt recitation of such troubling details, “could have been better, baby,” embodies loss in its very spareness and dizzying understatement.

“The White Album” famously begins with the line, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” then proceeds to systematically unravel the premise, suggesting it is no longer possible in a troubled time. Her unflinching, personalized journalism has the heat and danger of the just-experienced, when the ultimate outcome still remains to be seen. As told in their memoirs, Smith and Richards are prodigious survivors with the privilege of distance, and look backwards at the same era with clarity and empathy for their younger selves. It’s not their affect to be haunted, or mythologizing. That famous haircut of Richards’s that Smith co-opted to such effect? “I was never really interested very much in my look, so to speak,” Richards explains. “Though I might be a liar there,” he adds, with his ear for a good trickster tale. You can almost see his grin on the page, irrepressible joie de vivre bubbling up, just for life itself, even as loss quietly expands.

This post may contain affiliate links.